Astronomy - Juno Makes First Science Pass at Jupiter

On August 27th, NASA's Juno made its closest pass to the giant planet. All its instruments were on — here's what we learned.

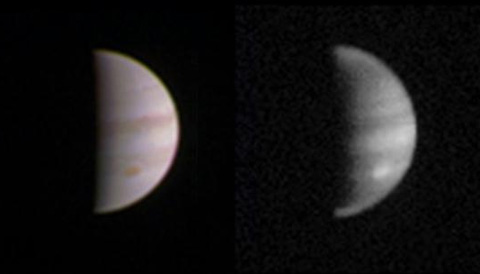

A dual view of Jupiter snapped by Juno from 2.8 million miles distant on August 23, 2016. In addition to the color view at left, JunoCam recorded a near-infrared wavelength (right) sensitive to the abundance of methane in the atmosphere.

NASA / JPL / SWRI / MSSS

NASA / JPL / SWRI / MSSS

NASA's latest mission to the outer solar system treated us to some amazing images this past week, as Juno swept just 2,600 miles (4,200 km) above the Jovian cloudtops.

“Early post-flyby telemetry indicates that everything worked as planned and Juno is firing on all cylinders,” says project manager Rick Nybakken (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) in a recent NASA press release.

A composite Juno image of Jupiter's north pole, as assembled by S&T Imaging Editor Sean Walker. He writes, "Junocam uses a drift-scan camera, and the images come down in strips that have to be assembled per color. There's additional smear due to the planet’s rapid rotation, which I corrected using distortion tools in Photoshop."

NASA / JPL / SwRI / MSSS / S. Walker

NASA / JPL / SwRI / MSSS / S. Walker

Closest passage, called perijove, occurred on August 27th at 13:44 Universal Time (UT). At that moment Juno was moving at an amazing 130,000 mph (58 km per second) — fast enough to travel from Earth to the Moon in just under 2 hours. For comparison, satellites in geostationary orbit are almost nine times farther from Earth than Juno was from Jupiter last weekend.

Juno is currently in a pair of preliminary 53.5-day-long capture orbits. It will fire its main engine one final time, on October 19th, before settling down in a series of much tighter, 14-day orbits to conduct its scientific observations.

This was also the closest non-destructive pass of Jupiter made by any spacecraft ever. To date, only two spacecraft have taken the plunge into Jupiter's dense atmosphere: the Galileo atmospheric probe (1995) and its companion orbiter (2003).

Launched on August 5, 2011, from Cape Canaveral, Juno made a pass near Earth on October 9, 2013, and entered polar orbit around Jupiter on July 5, 2016 (July 4 Eastern Daylight Time).

The mission's goals are to probe the composition of Jupiter and measure its polar magnetosphere, magnetic and gravitational field. For example, we may soon know if Jupiter has a solid rocky core, or instead if its center is simply a super-dense ball of metallic liquid hydrogen.

Juno also holds the distinction of being the only spacecraft to operate in the outer solar system using solar panels instead of plutonium-fueled radioisotope thermoelectric generators(RTGs).

August 27th marked the first of 36 close flybys planned before the mission ends in February 2018 with entry into the Jovian atmosphere. To carry out its mission, Juno must thread the intense radiation belts surrounding Jupiter on successive polar passes. All instruments came through this first pass unscathed, though Juno is expected to suffer from radiation degradation on each consecutive pass.

Brave New Gas Giant

And going into this U.S. Labor Day weekend, NASA released some stunning closeup images from the flyby. Just downloading the data collected via the Deep Space Network during the 6-hour passage as Juno transited Jupiter from pole to pole took a day and a half.

Already, Juno is revealing the giant planet's secrets. “First glimpse of Jupiter's north pole, and it looks like nothing we have seen or imagined before,” said principal investigator Scott Bolton (Southwest Research Institute-San Antonio) in a recent NASA press release. “It's bluer in color up there than other parts of the planet, and there are a lot of storms.”

Aurora as seen by JIRAM over Jupiter's south pole in the infrared range of 3.3 to 3.6 microns.

NASA / JPL / SWRI / ASI / INAF

NASA / JPL / SWRI / ASI / INAF

Indeed, as seen by JunoCam, the spacecraft's visible-light camera, it scarcely looks like the same belt-festooned planet that we're used to seeing. Jupiter's poles are dappled with swirling storms and depressions, many casting conspicuous shadows. Unlike at Saturn, no "polar hexagon" graces Jupiter's poles.

Juno's Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM), supplied by the Italian Space Agency was also fired up for this pass. As expected, JIRAM gave researchers the first-ever view of Jupiter's southern aurorae. Its infrared observations, made from 3.3 to 3.6 microns in wavelength, revealing a flurry of hydrogen ions energized by charged particles cascading in from the planet's magnetosphere. This angry, swirling abyss is a dramatically new perspective, as Jupiter's southern pole is unfavorably placed for observation from Earth.

Check out this amazing video dropped last Friday of JIRAM scanning Jupiter in the infrared:

Juno's Radio/Plasma Wave Experiment also recorded the ethereal sounds of radio emissions during the pass. Although Jovian radio outbursts have been known since the 1950s, we've never recorded them at such close range.

Plenty of Juno Science to Come

Jupiter reaches conjunction on the far side of the Sun later this month, on September 26th, marking a week of limited contact between Juno and Earth. But once the spacecraft returns to perijove again on October 19th and powers itself into its final orbit, the science results will start to flow. Thebest is yet to come. For example, JunoCam is expected to deliver some of the highest resolution images of the Jovian cloud tops yet.

There's also a concerted effort for Earthbound amateur astronomers to monitor Jupiter as a backup for Juno's observations.

One thing Juno won't examine up close are the Jovian moons. Due to the nature of its mission, Juno orbits Jupiter far out of its moons' orbital planes. We'll have to wait until the launch of Jupiter Icy moons Explorer (JUICE), the next mission to Jupiter in the pipeline, for more moon pictures.

Polar perspectives of Jupiter, old and new. The view from Pioneer 11 in 1974 (left) and Juno in 2016 (right).

NASA / JPL; D. Dickinson composite

NASA / JPL; D. Dickinson composite

No comments:

Post a Comment