Astronomy - A Little Guide to Lunar Domes

With this week's waxing Moon, we set off to explore its volcanic past with a look at a dozen intriguing lunar domes.

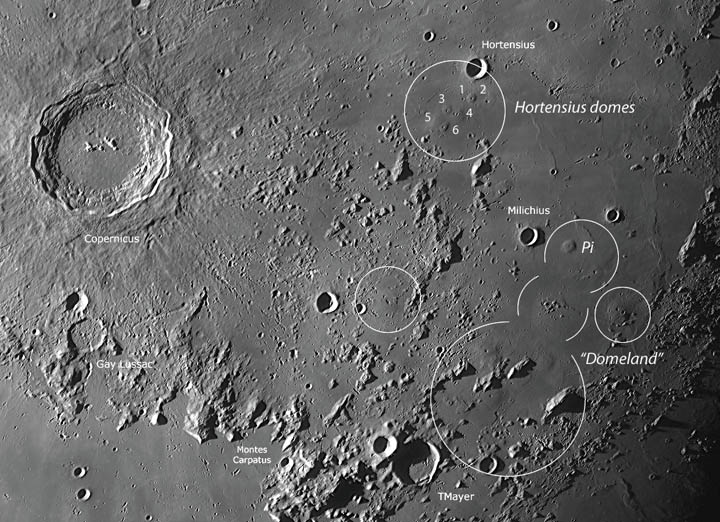

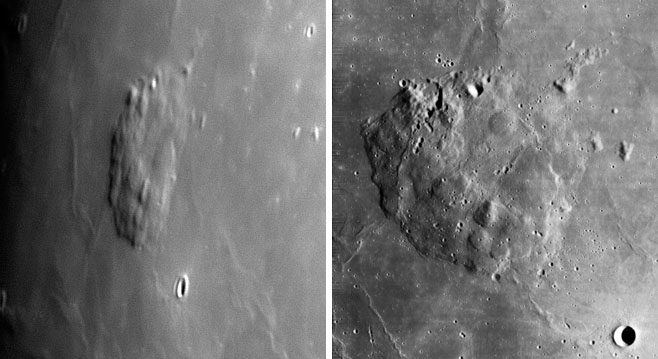

One of the best known lunar dome fields is located just north of the crater Hortensius not far from the crater Copernicus. In this and the following photos, south is up unless otherwise indicated.

Mike Wirths

Mike Wirths

In the coming week, the Moon will wax from a thick crescent to nearly full. Most of us will put deep-sky observing on hold as lunar glare intrudes on dark skies. Instead of capping your scope, why not make the Moon your focus? If you haven't already, it's a good time to get acquainted with one of our satellite's most evocative features: domes.

Many of the Moon's characteristic landscapes were created by impact. Craters, rays, mountain ranges, maria, and basins abound. Lunar domes are different. They formed as a result of the Moon's own internal volcanism. Similar to shield volcanoes in Iceland, Hawaiʻi (including Mauna Kea on the Big Island), and Olympus Mons on Mars, they form when highly fluid lavas erupt through a central caldera onto the surface. They're almost all of low-explosivity, unlike their cousins, the more violent stratovolcanoes that grab the headlines.

As sheet after sheet after sheet of lava oozes up from beneath the crust, a dome slowly builds up over time into a broad, gently-sloped mound shaped like a warrior's shield with a raised center and lower edge. Shield volcanoes can be small like the Icelandic and lunar varieties, or broad and massive like Olympus Mons. A typical lunar dome measures between 5 and 7.5 miles (8-12 km) in diameter with a peak or caldera ~900 feet (~300 meters) high. Slopes are very gentle — only a few degrees at most — making for very easy walking should astronauts ever get the chance to explore one.

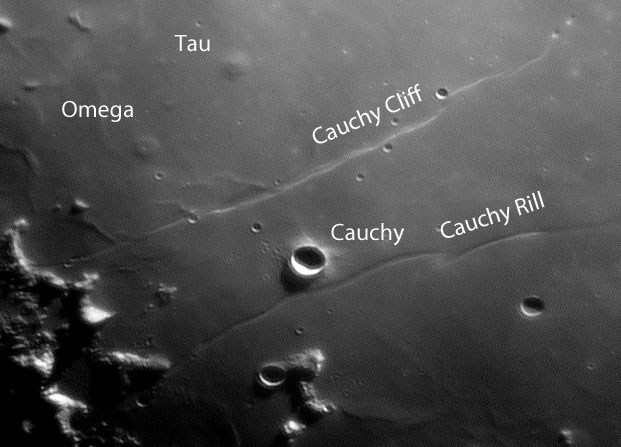

There's a lot to see near the crater Cauchy: a rill; cliff; and two good-sized domes, Omega (diameter 6.2 miles / 10 km) and Tau (8.7 miles / 14 km). Both rise about 650 feet (200 m) above the surrounding mare. Omega's summit crater, with a diameter of 1.2 miles (2 km), is one of the easier ones to see in a modest telescope.

Oliver Pettenpaul

Oliver Pettenpaul

Over 300 lunar domes are known, with many visible in amateur telescopes with apertures from 3-inches on up. We'll look at the historically most interesting and easiest examples along with a few oddballs tossed in to keep things lively. There are two key requirements for happy dome watching — steady atmospheric seeing and observing the dome near the terminator shortly after lunar sunrise or before sunset.

Most domes are subtle, low contrast features that turn mushy in poor seeing. Low light, the kind that produces long shadows from peaks and crater rims, brings out their gently sloping forms and provides the best contrast. Don't bother dome hunting when the Sun rides high in the lunar sky. No shadows, no domes!

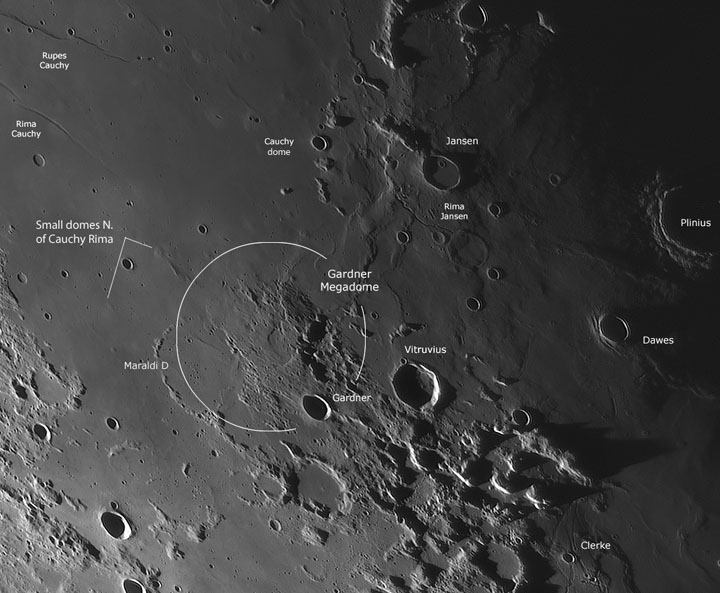

This enormous "bubble" or rise called the Gardner Megadome is 38 miles (61 km) across and features a large depression at its center suspected of being a volcanic caldera. The west side (lunar west) of the Megadome is rugged, while the east appears to have been smoothed over by lavas.

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hofmann

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hofmann

Under good light and excellent seeing, domes look like swellings or blisters on the lunar surface. Many appear almost smooth, though a few have rougher areas that again show up best in low, slanted sunlight. I get most excited when I can tease out a caldera. Seeing the summit blow-hole, you really see a dome for what it is: a formerly active volcano back in the Moon's rough and tumble days.

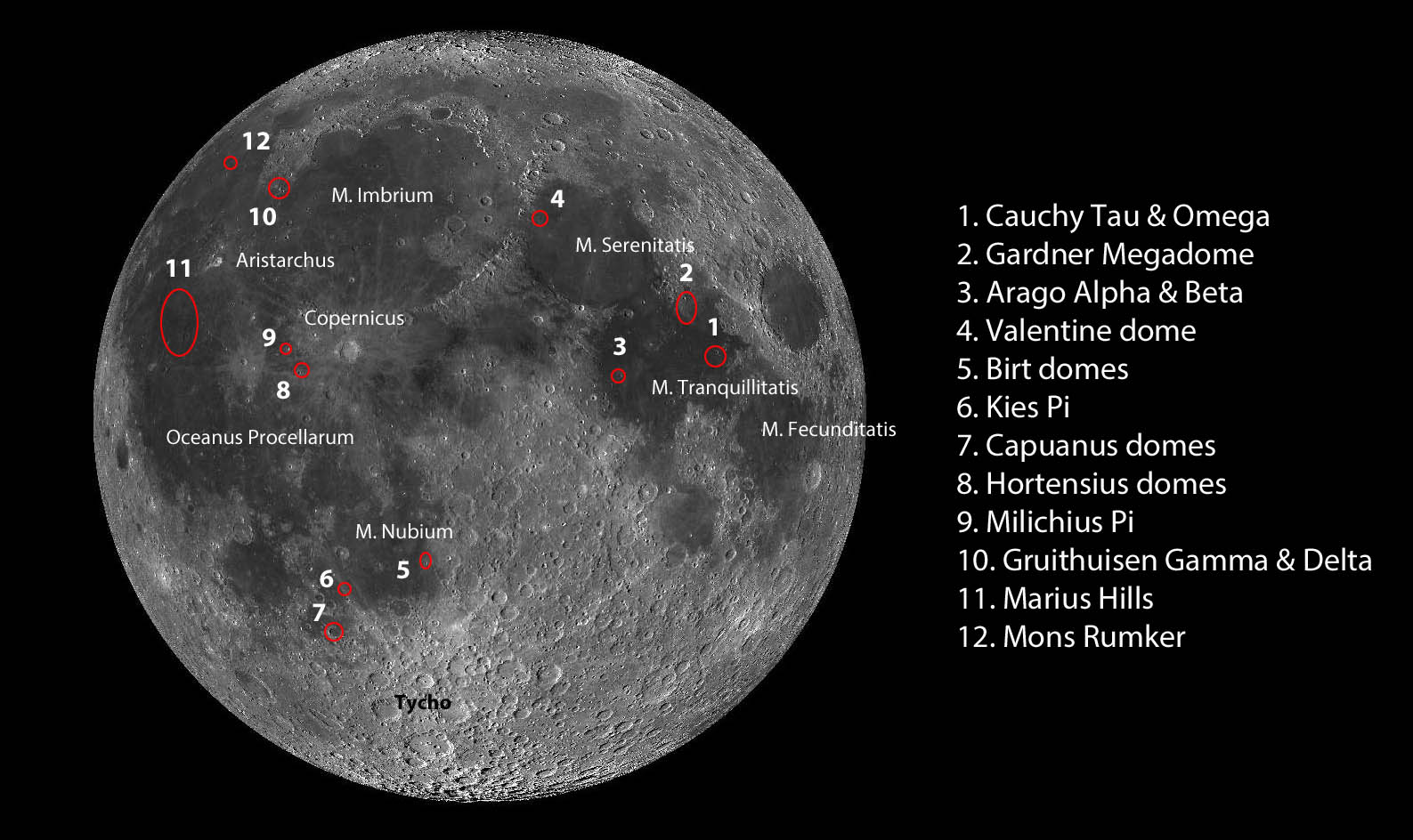

This map of the Moon shows the locations of a dozen key domes or dome fields within easy reach of amateur telescopes. The table at right identifies each by number.

Bob King using the ACT-REACT Quickmap / LRO / NASA

Bob King using the ACT-REACT Quickmap / LRO / NASA

The full-disk map above plots the general location of each of the featured domes followed by individual descriptions. If you're thwarted by poor seeing or discover that the dome you hope to view is too far from the terminator to make out this lunation, save it for the next. Persistence will eventually reward you with a thorough working knowledge of the Moon's bumps and lumps. You may even discover a newfound eagerness for the Moon's return after dark nights!

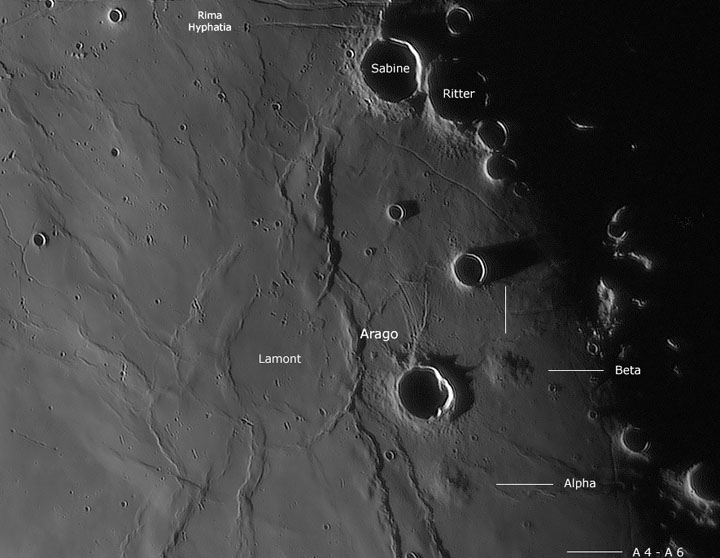

The easy-to-spot Arago domes are both about 15 miles (24 km) and more rugged than most with textured surfaces best seen in low, slanted sunlight. Both are about 980 feet (300 m) high.

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

Use the list below as a general guide to know when lighting is best for viewing a particular dome or dome complex. If the day falls within the current viewing period, a calendar date is included:

* Cauchy domes: 4 days past new

* Gardner Megadome: 5 days

* Arago domes: 6 days (Sept. 7th)

* Valentine dome: 7 days (Sept. 8th)

* Birt domes: 8 days (Sept. 9th)

* Kies Pi and Capuanus crater: 9, 10 days (Sept. 10-11)

* Hortenius and Milichius domes: 10 days (Sept. 11th)

* Gruithuisen domes: 11 days (Sept. 12th)

* Marius Hills: 12 days (Sept. 13th)

* Mons Rümker: 12, 13 days (Sept. 13-14)

* Gardner Megadome: 5 days

* Arago domes: 6 days (Sept. 7th)

* Valentine dome: 7 days (Sept. 8th)

* Birt domes: 8 days (Sept. 9th)

* Kies Pi and Capuanus crater: 9, 10 days (Sept. 10-11)

* Hortenius and Milichius domes: 10 days (Sept. 11th)

* Gruithuisen domes: 11 days (Sept. 12th)

* Marius Hills: 12 days (Sept. 13th)

* Mons Rümker: 12, 13 days (Sept. 13-14)

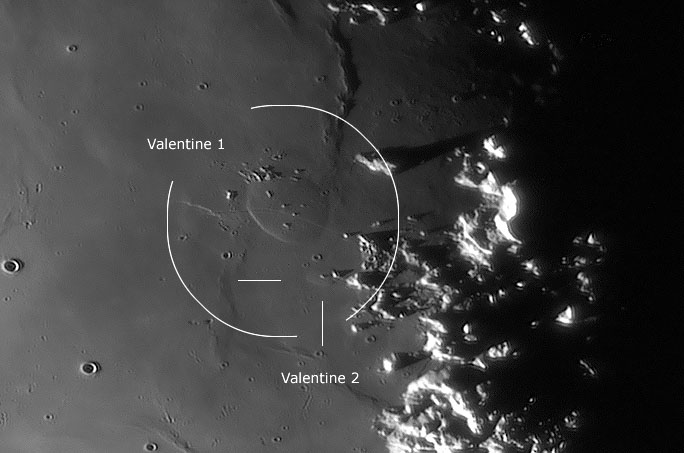

Looking for that special gift next Valentine's Day? Show your sweetheart the Valentine Dome. One of the larger domes, it measures about 18.6 miles (30 km) and is dotted with small protrusions. You'll find it on the northwestern shore of Mare Serenitatis adjacent to the Caucasus Mts. A second smaller "heart" lies a short distance to the north.

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

To make the most of your observations, consider the following at each feature:

- Note the surroundings, whether highlands or sea (mare). You'll soon discover that more domes are found within and near the maria and are undoubtedly related to mare volcanism.

- Size and shape. Is it small, large? Elliptical – circular – polygonal – irregular?

- Steepness of the incline. Is the dome's gentle, steeper?

- Study the shape of the summit. Is it flat – multiple – complex?

- Can you discern a central depression (caldera) or does the top appear smooth? Are there any rills cutting through or near the dome? Sinuous rills once channeled lava.

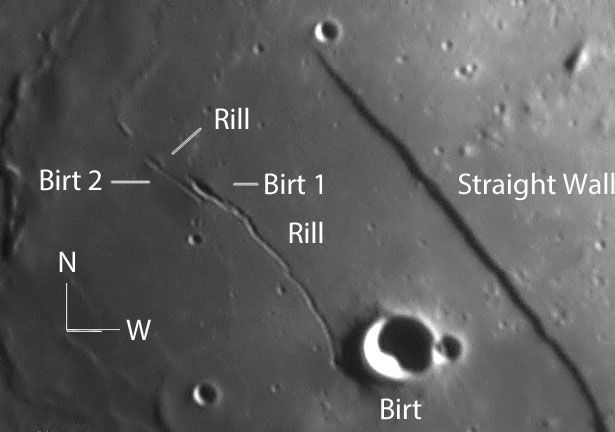

Birt is easy to find thanks to its proximity to the famous Straight Wall, a lunar fault. Once there, follow the Birt Rill north to two small domes, each bisected by a narrow rill. Use high magnification on this one.

Jim Phillips / co-author "Lunar Domes"

Jim Phillips / co-author "Lunar Domes"

The above list of descriptors is based on a more detailed one compiled by the American Lunar Society Lunar Dome Section. Take a read when you get a moment. Now I'll get out of the way, so you can begin your work as an amateur lunar volcanologist.

About 6 miles (10 km) across, Kies Pi is simple to find due east of the Kies Crater in Mare Nubium. The 6-mile-wide (10 km) dome is topped by a summit caldera, visible in excellent seeing in a modest telescope using high power.

Oliver Pettenpaul

Oliver Pettenpaul

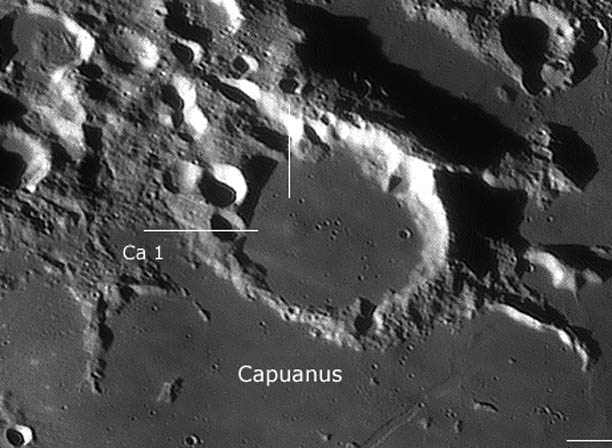

Several craters have swellings and domes in their interiors including Capuanus. The most prominent one is marked, but several more are visible in low light.

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

Copernicus is a wonderful place to begin your exploration of the half-dozen domes north of Hortensius Crater but also Milichius Pi and an entire region of bubbly Mare Insularum between Milichius Pi and Tobias Mayer Crater. Rich in domes, the region's nicknamed "Domeland." Milichius Pi and several of the Hortensius domes show small depressions at their summits.

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

Side by side Gruithuisen Gamma and Delta look like loaves of bread to me, though lunar atlas creator Antonín Rükl compares Gamma to an upturned bathtub. Unlike most domes, these two are steep and tall. Gruithuisen Gamma has a diameter of 11.8 miles (19 km) and a height of 4,330 feet (1,320 m) , while the eastern dome, Gruithuisen Delta, has a diameter of 16.8 miles (27 km) and towers 5,347 feet (1630 m) high. Look for the summit caldera on Gamma.

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

Wolfgang Paech and Franz Hoffman

Lucky is the observer who happens to catch a look at theMarius Hills when the Sun barely grazes their tops. They look like so many pinpricks or pimples when the light's just right. Located in the western portion of the Moon, this extensive dome field contains swells with an average height of 600 to 1,640 feet (200–500 m).

Jim Phillips

Jim Phillips

Mons Rümker forms a large, pudding-like mound of some 30 domes piled one atop the other in far western Oceanus Procellarum. The feature appears quite foreshortened near the limb as shown by its overhead appearance in a photo taken Lunar Orbiter 4 (right). The mound is about 43 miles (70 km) across and climbs to 3,608 feet (1,100 m) above the plains. Rümker represents multiple, massive outflows of lava. Amazing!

Oliver Pettenpaul (left) / NASA

Oliver Pettenpaul (left) / NASA

No comments:

Post a Comment