Astronomy - Orbital Path 11: Black Hole Breakthroughs

Michelle Thaller talks with three leading scientists about black holes - how do we know they exist, where do they come from, and how can we learn more about a black hole without getting too close?

Most of the time, science marches slowly forward in methodical, well-measured beats. But sometimes there is an exquisite agony to scientific discovery. Times where you see something unexpected, or something you did expect but never quite let yourself believe was real.

When it comes time to publish those results, when it’s time to claim that you have discovered something extraordinary, there is almost always a barrier of fear to get over. Did you really see what you thought you saw? Did you make some simple mistake that the readers of your paper or the listeners to your conference presentation will immediately see and use to dismantle your result? Of course you’ve passed this by some of your trusted friends and colleagues, but at the end, it’s just you up there, staking your professional reputation on a risky, if exciting assertion.

Do Black Holes Exist?

In astronomy, there are few topic more slippery than black holes. By their very nature, they are nearly impossible to detect, unless something is falling into them. And while the idea of black holes was postulated literally centuries ago, for ages no one could tell whether they were just an example of our mathematics run amok, or whether these beasts were real. Really, real.

It may surprise you to know that the existence of black holes, at least our current model of them, is still controversial. Prominent scientists such as Stephen Hawking still wonder if the laws of thermodynamics truly allow an event horizon, the point of no return around a black hole, to exist.

There is no doubt that there are super-compact bodies with huge gravitational fields that lie in the core of galaxies or can be watched sucking away the lifeblood of stars. But are they black holes, or something we have yet to understand? Do we understand how a black hole would really work? What is the best evidence we have the black holes exist? Could we, for the first time, have witnessed the birth of a black hole?

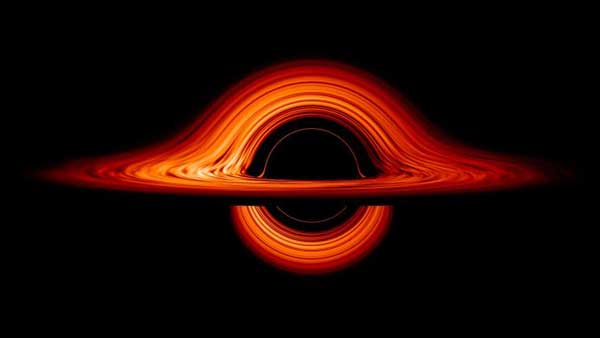

This simulation frame shows a black hole accretion disk. Created by Jeremy Schnittman and inspired by the movie Interstellar.

In this episode of Orbital Path, we speak to three astronomers who have worked to piece together the best evidence yet for the existence of black holes. Decades ago, Paul Murdin worked on early observations of an area of the sky that was mysteriously bright in X-rays, super high-energy light that shouldn’t have been present around a normal star. To make matters even more dramatic, that star was seen to be orbiting a massive object that was, except for its X-rays, invisible. These observations, among others, helped astronomers finally embrace the incredible idea that there really was a black hole in the constellation Cygnus.

Jeremy Schnittman uses mathematics and Einstein’s equations to model what the area close to a black hole would look like, and works on strategies to find the possible millions of black holes that lurk dark and unseen in the Milky Way.

And Christopher Kochanek may have had the tremendous luck (coupled with a brilliant program to monitor the skies) to catch the exact moment a black hole was born. What is it like to make that claim, that you are the first person to see the birth of a black hole? Do these people still suffer doubts about the reality of black holes? There may still be a good deal of wiggle room, but as you’ll hear in the podcast, Kochanek, at least, is willing to bet his life –and your dog’s!

No comments:

Post a Comment