Astronomy - Mercury Punctuates The False Dawn

Early risers get a triple treat this week and next: a ravishing dawn Moon, an excellent apparition of Mercury, and a hint of Halloween in the ghostly zodiacal light.

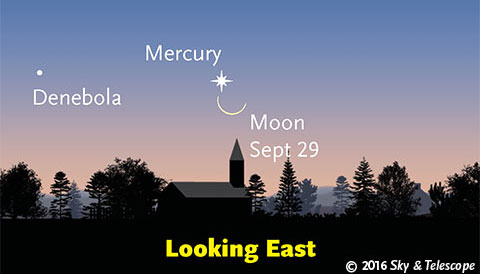

A wiry crescent Moon will be in conjunction with Mercury low in the eastern sky Thursday morning. Look for the pretty combo about 8° high around 45 minutes before sunrise.

Synchronicity is a beautiful thing. Just as the Moon departs the morning sky this week, Mercury puts in a fine appearance and the zodiacal light comes out of hiding.

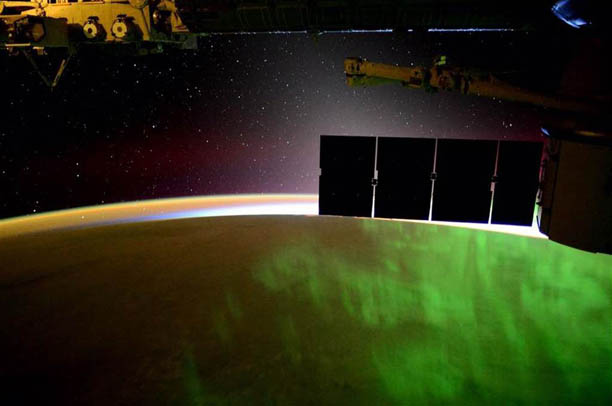

And there's more! Before the Moon bows out on Thursday morning (September 29th), its slender crescent will dangle just 1.5° to the south of our solar system's innermost planet. Skywatchers should also be alert tonight (September 28th) and tomorrow night for the aurora borealis. NOAA's space weather prediction center expectsstrong solar winds emanating from a large solar coronal hole to spark moderate G2 geomagnetic storms both nights.

Once the Moon departs the scene, Mercury remains, brightening to negative magnitude in the first week of October while slowly slipping back toward the horizon. During this time, the zodiacal light puts in a great appearance, its best of the year for mid-northern latitude skywatchers. We have a two-week window of dark sky for sampling this tenuous delectable before the Moon returns in mid-October. A second window opens from October 28th through November 10th.

A tapered cone of zodiacal light tilted up from the eastern horizon last fall at the start of dawn. You can start watching for the light about 2 hours before sunrise. The closer to dawn, the higher the cone rises. It's brightest at its base, comparable to the summertime Milky Way, and dimmest at its tip, about equal to the fainter sections of the winter Milky Way.

Bob King

Bob King

Composed of dust shed by comets and released byasteroid impacts, the zodiacal light gets its name from its location: it resides along the zodiac, a 16°-wide band of sky centered on the ecliptic, the great circle that defines the plane of the Solar System. The tapered cone of dust extends roughly to Jupiter's distance in a thin, flat disk, giving it a very approximate diameter of a billion miles. Outside of the solar wind, it's one of the largest entities in the Solar System.

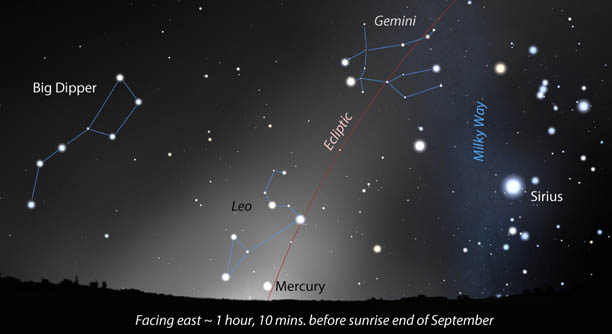

In the coming week, watch for fall's solitary bright morning planet, Mercury, to appear at the base of the zodiacal light just as the light of dawn gathers. This map shows the sky from about latitude 42° north 70 minutes before sunrise.

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

The zodiacal light is broadest and brightest near the horizon because the fine dust is physically closer to the Sun and delivers a more intense reflection. As you follow up the length of the cone, your gaze takes you farther and farther from the Sun and the finger of light fades.

If you're fortunate enough to observe under truly pristine skies, the zodiacal light doesn't stop there but continues as the zodiacal band across the entire length of the ecliptic, brightening a bit at the anti-Sun position into a fist-wide patch called the gegenschein. I've seen extensions of the zodiacal cone but have never glimpsed the complete arc even from my darkest observing site. Someday!

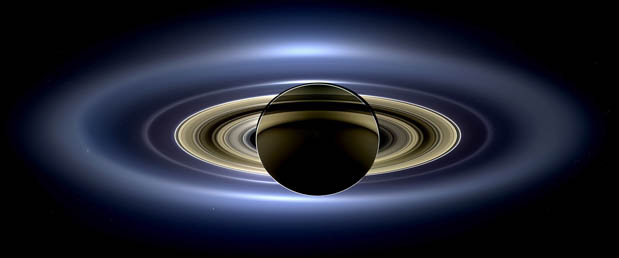

In this photo montage taken by NASA's Cassini spacecraft in July 2013, the Sun is hidden by the ball of the planet. Forward scattering of sunlight makes the faint outer rings stand out.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute

The dust particles range in size from coal dust to very fine beach sand (0.01–0.3 mm) and reflect light via forward scattering, that is, the dust, which is illuminated from behind by sunlight, scatters the light forward in our direction. As long as the brilliant source is hidden, and the material is seen against a dark backdrop, forward scattering can take a wispy thing and make it look very substantial. If you live in a cold climate, you've probably seen your own breath as brilliant swirls of vapor when backlit by the low Sun — a close-to-home example of forward scattering.

NASA astronaut Terry Virts tweeted this photo from the International Space Station on April 26, 2015. In it we see the diffuse glow of the zodiacal partially hidden by a solar panel, airglow (to the left), and the aurora australis or southern lights. Because the zodiacal light mimics the appearance of morning twilight, it's also called the "false dawn."

Terry Virts / NASA

Terry Virts / NASA

In photos taken from the unique vantage point of theCassini space probe, we see Saturn's tenuous, outer rings light up for the same reason. It doesn't take much material to create a spectacle, either. The separation between individual dust partlcles in the zodiacal light is about 5 miles (8 km) according to a study by Dutch astronomer H. C. van de Hulst. While tiny, the volume of space they occupy is huge. That and the effectiveness of forward scattering make these mere motes a most impressive sight from a dark sky.

The LADEE Moon orbiter took this image of the zodiacal light as the cone rose along the lunar limb on April 12, 2014, just five days before the probe crashed into the Moon.

NASA Ames

NASA Ames

You can begin watching for the zodiacal light ~2 hours before sunrise. Look for a weak, diffuse, thumb-shaped glow extending from the head of Leo, the Lion, in the north-northeastern horizon up through Cancer and into Gemini until it meets and blends into the tilted band of the winter Milky Way. This time of year it's easy to imagine it as the Lion's breath condensing into vapor on a chilly fall morning.

The light reaches greatest intensity, height, and spread in the opening minutes of dawn, when the eastern horizon begins to pale. Remember to cast your visual net wide. Where it roots at the eastern horizon, the zodiacal light is some 30° or three fists wide and at least six fists from top to bottom. It's also brighter than you might think, especially the lower half closer to the horizon (and the Sun). Some observers liken it to a light dome from a distant city.

Mercury (lower left) was bright and easy to spot this morning one hour and 15 minutes before sunrise in the eastern sky below the Moon. Tomorrow, the two will be in conjunction.

Bob King

Bob King

While you don't need a completely foreground-free horizon to see the zodiacal light (owing to its size), you will need one if you want to see Mercury ascend from its base. Watch for the planet to clear the horizon just about the time the cone pales in the bluing sky. I saw them both this morning around 5:45 a.m. along with the amazing earth-lit Moon.

From the northern hemisphere, fall mornings in the eastern sky (left) and spring evenings in the west are the best times to see the zodiacal light. It's then that the ecliptic is angled most steeply to the horizon, tilting the otherwise faint light cone to best advantage.

Bob King

Bob King

Fall mornings are best for zodiacal light viewing in the northern hemisphere because the angle the ecliptic makes to the horizon tilts upward and to the north, ensuring that the "false dawn" stands high and clear of the horizon haze. The favorable tilt repeats itself on spring evenings in the western sky; other times of year, the ecliptic is more nearly parallel to the horizon and the dusty blush is swamped by atmospheric absorption at low altitude.

A lingering crescent, a hide-and-seek planet, and a pyramid of light constructed of comet and asteroid castoffs. Such sights of arresting beauty await those who rise with the dawn.

No comments:

Post a Comment