Astronomy - Plant Your Eyes In Delta Cephei’s Fertile Triangle

The famous variable star Delta Cephei unlocks a box of deep-sky treasures in a little-visited corner of Cepheus, the King.

Cepheus, the King, and the triangle of naked-eye stars headed up by Delta (δ) Cephei are well placed in the northern sky now through mid-winter. This map shows the sky facing north around 9:30 p.m. local time in mid-October.

Stellarium

Stellarium

I like to plan my deep-sky observing forays by selecting a familiar bright star situated near a diverse mix of clusters, double stars, nebulae, and galaxies. Using an atlas and the star as my waypoint, I happily plunge into the unknown.

While I enjoy the challenge of seeing the next-to-impossible, my favorite deep-sky perambulations are those that include both bright and faint objects.

There are two reasons for this. After tackling a faint and difficult nebula, moving on to a bright star cluster feels like a well-earned vacation. Sweet relief! Secondly, bright and faint celestial targets complement and define each other much as pain and joy do in a life. We learn the limits of our eyes and instruments while getting a taste of everything the universe has to offer.

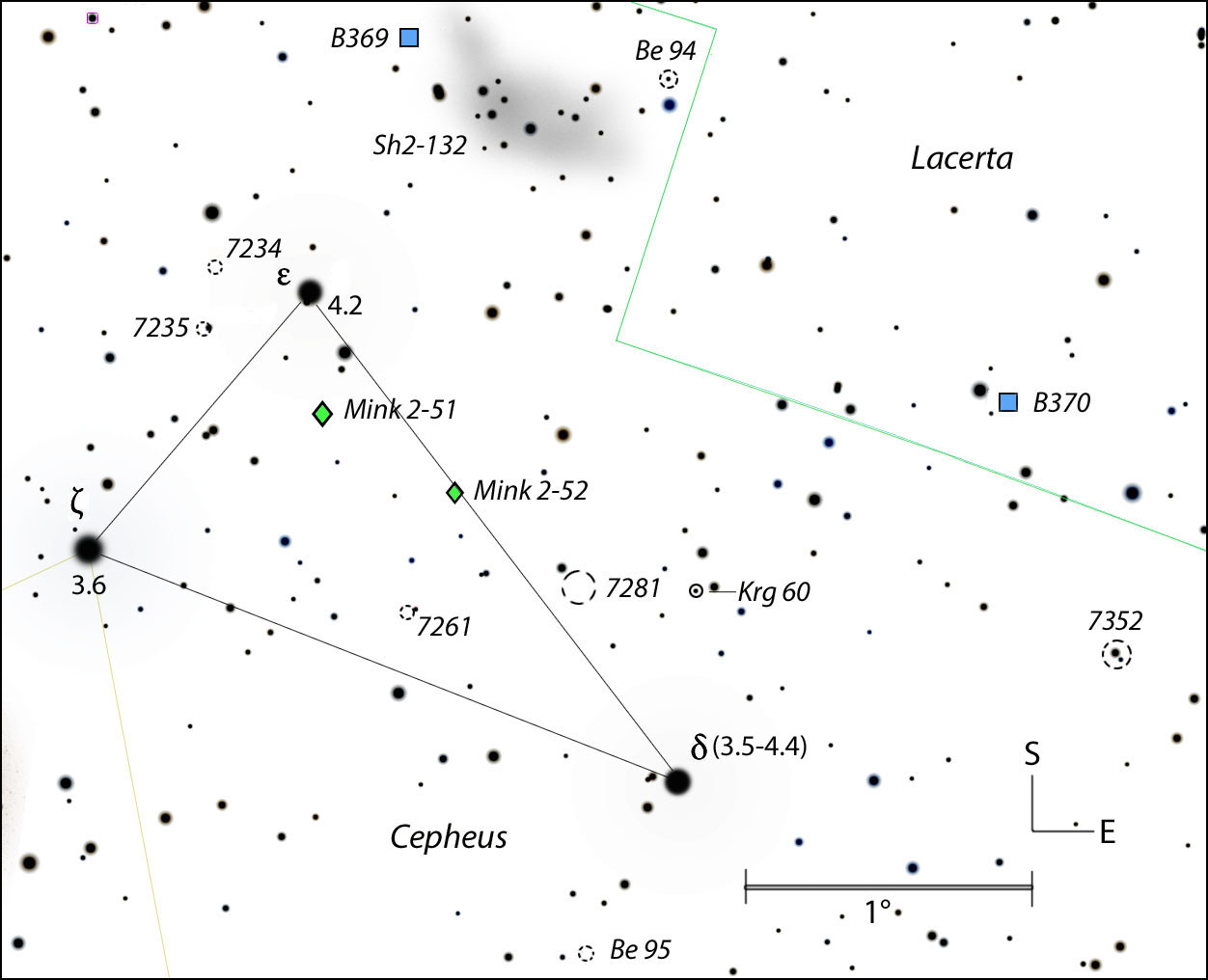

For all these reasons, a triangle of cosmic real estate in Cepheus measuring just 3.5° × 2° makes for a wonderful place to roll out the star map and leave Earth behind for an evening.

We'll start with Delta (δ) Cephei, the prototype star of the Cepheid variables, arguably the most important class of variable stars in the sky. Since Henrietta Leavitt's discovery of Cepheids as "standard candles" and Edwin Hubble's application of what came to be called the period-luminosity relationship to Cepheids in the Andromeda Galaxy in 1923, the scale of the known universe dramatically expanded overnight. At the time, it must have felt like getting kicked out of the nest.

Delta Cephei is a bright, easy double star with a nice color contrast. On the morning of Monday, October 10th, the Delta primary shone at magnitude +4.2.

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

Delta's light varies between magnitude +3.5 and +4.4 every 5.36 days as the star expands and contracts, alternately fading and brightening with a precise rhythm. By happy coincidence, we can easily track Delta's variations using the other two stars in the triangle, Zeta (ζ)Cephei (magnitude +3.6) and Epsilon (ε) Cephei (+4.2).

Delta has a classic roller coaster-shaped light curve, rising rapidly to maximum in a day and a half followed by a slower 4-day fall to minimum.

Not only does Delta make a wonderful naked-eye variable star, but even a small telescope will show it as a bright, attractive double star with a golden primary and pale blue-white, 6th-magnitude companion lying 41″ to the south-southwest. At first glance, it resembles Albireo in Cygnus.

The little triangle outlined by Delta, Zeta, and Epsilon Cephei and vicinity are home to more than a dozen deep-sky objects for small and larger telescopes. South is up and stars are shown to magnitude +9.5. Click for a larger version.

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

From Delta we glide about ⅔° south to another unique double star, Kruger 60, a tight pair of red dwarfs and one of the closest stars to Earth at a distance of just 13.1 light years. Kruger 60A shines at magnitude +9.8; its +11.4-magnitude companion, Kruger 60B, huddles about 1.7″ to the northwest. The duo was closest in 2014 and is slowly widening toward a maximum separation of ~4.8″ in 2036. The period is 44.5 years. I had no problem splitting the two in a 6-inch telescope back in the early 1990s, but they were tough work this season. Seize a night of good seeing and use high power!

Use this detailed finder chart with stars to magnitude +10.5 to navigate to the binary star Kruger 60. The star forms a small right triangle with two similarly bright stars and shows a distinctive orange-red hue. Click to enlarge and print for use at the telescope.

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

Typical of red dwarfs, both A and B have very low luminosities with masses only a fraction of solar. The pair also has a large proper motion of nearly 1″ per year (0.86″), fast enough to see them drift against the background stars in just a few years time. Photos or sketches made now and two years down the road would make a worthy observing project. Finally, the secondary star is subject to random but brilliant stellar flares that can more than double its brightness temporarily. Keep an eye out for these rare events.

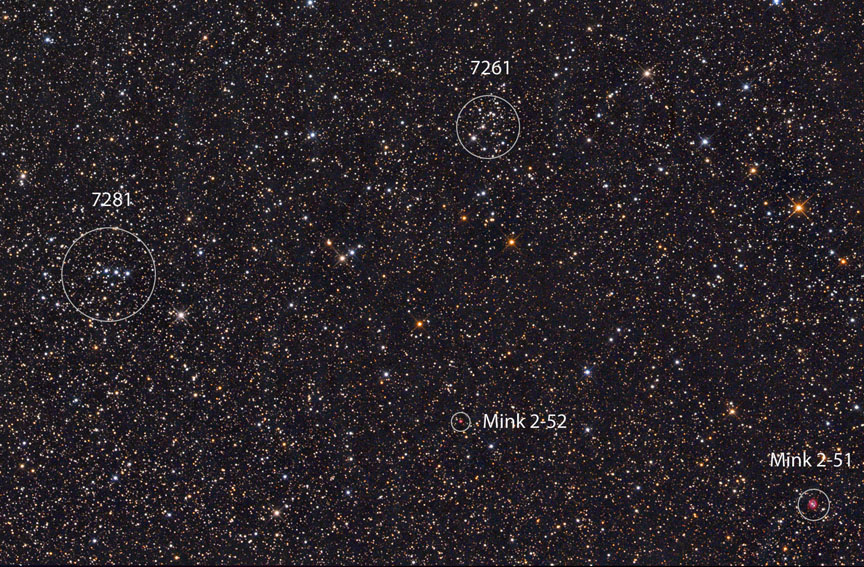

The core of the Delta triangle includes two NGC open clusters and two Minkowski planetary nebulae.

Gregg L. Ruppel

Gregg L. Ruppel

One-half degree due west of the binary, you'll run into the large and moderately rich open cluster NGC 7281. Although not particularly compact, the cluster features a nice mix of bright and faint stars highlighted by three 10th-magnitude stars in a neat line that recalls Orion's Belt. Another smaller open cluster, NGC 7261, lies not quite 1° to its west. About a third as large and moderately compact, its shape reminds me of a squat arrowhead. Both are low-power objects that should be visible in 6-inch and larger telescopes.

Additional Observing Targets

- Minkowski 2-52: A challenging 14th-magnitude planetary nebula with a diameter of 12″. Nothing was visible in my 15-inch at 142× until I screwed on a Lumicon UHC filter and studied the location with all the averted vision I could muster. Then I saw it — a small disk with a slightly brighter center flickering in and out of view.

Listed at magnitude +13.6, I found the planetary nebula Mink 2-51 easy to spot with an O III filter at magnifications of 67× and 142×.

DSS

DSS

- Minkowski 2-51: Continuing west, you'll quickly run into this much easier and larger planetary that measures 47″ × 38″ and shines at magnitude +13.6. Visible without a filter at 142×, I discerned a soft, round disk dotted by two very faint stars of magnitude +14.5 and 1+5.5. Since my source, the Strasbourg-ESO Catalog of Galactic Planetary Nebulae (Parts One and Two), lists the central star at magnitude +20.4, I have to assume both are foreground suns. An O III or UHC filter makes M2-51 an easy catch.

- NGC 7235 and 7234: Next, we move on to a contrasting pair of star clusters near Epsilon Cephei. I highly recommend NGC 7235, a 5′ wide, 8th-magnitude, moderately compact group shaped like a backwards letter "S." Be sure to look for the 10th-magnitude red star along its eastern border. NGC 7234 lies just 15′ south of 7235. Due to errors in recording the cluster's position when it was first discovered by William Herschel, some publications refer to it as "non-existent," but I saw a faint, nebulous patch some 3′ across at the position shown in Uranometria 2000.0. I could even resolve nearly a dozen +13.5- to +14.5-magnitude stars. Were these random alignments or ...?

- Sharpless 2-132: A beastly, large emission nebula faintly visible without a filter but oh-so-much finer with a low-power, wide-field eyepiece coupled with an O III filter. The brightest section, about ½° long and extended east-west, is centered on a field so rich in stars, it shimmers like a glitter-coated veil. I was able to follow one particular "byway" of the nebula an additional degree to the west. A real find if you own a rich-field telescope 8-inches or larger.

- Dark nebula Barnard 369 and open cluster Berkeley 94 bracket Sh2-132. The dusky nebula is about 5′ across and quite vague, requiring averted vision. I saw it best at low power. Berkeley 94 lies just south of an orange-tinted +6.5-magnitude star. It's an amazing little object just 2′ across with two bright stars and a smattering of 8-10 more that together resemble the narrow snout of a fox. This tiny cluster packs a lot of pizzazz!

The extensive bright nebula Sharpless 2-132 makes a nice sight in a rich-field scope equipped with a nebula filter. North is up.

Sharplesscatalog.com

Sharplesscatalog.com

- If you turn around and head back 2° to the west, you might or might not see the difficult dark nebulae,B370, just over the border in Lacerta. It wasn't easy in the 15-inch at low magnification. Let's just say I suspected seeing a hint of darkening at the correct location.

- NGC 7352: Two stars of magnitude +8.5 and +9.1 separated by 2′ were obvious, but the rest of the cluster was difficult to tease apart from the rich background field, so I felt a bit lost here as to which stars belonged to the cluster and which did not.

- We end on a bright note, returning to Delta Cephei. A bit more than ½° to its north, look for Berkeley 95, a 3′-wide, faint, diffuse glow that splinters into several dozen dim suns ranging from magnitude +13 on down. It's much richer than you'd first suspect, especially for larger scopes. Use medium to high magnifications.

After dropping in on 14 deep-sky denizens, you might think we've exhausted this particular nook in Cepheus. Wrong! I've barely scraped the sky in our circumscribed star hop. Numerous additional open clusters, planetaries, and bright and dark nebulae pepper the region beyond the fertile triangle. The King gladly shares his treasure with all who seek it.

No comments:

Post a Comment