Astronomy - Resolving Andromeda — How to See Stars 2.5 Million Light-Years Away

At 2.5 million light-years away, you might think it's impossible to see individual stars in the Andromeda Galaxy. Let its largest star cloud, NGC 206, show you the way.

The Hubble Space Telescope easily resolves millions of individual stars in an outer region of the Andromeda Galaxy, also known as M31.

NASA / ESA / Hubble Heritage Team

NASA / ESA / Hubble Heritage Team

I always figured I'd have to wait until the next supernova to see an individual star among the trillion that comprise theAndromeda Galaxy. At the galaxy's distance of 2.5 million light-years, the stars blend into a luminous stellar fog. Whenever I show Andromeda to the public, I make sure to remind each viewer that the haze they see is actually the light of billions of individual stars too far and faint to resolve into individual pinpoints.

In binoculars and small telescopes, it's easy todistinguish the core, where stars are more strongly concentrated, from the less populated arms. Those with 10-inch and larger telescopes can survey the galaxy's brighter globular star clusters and stellar associations with the aid of detailed maps. But individual stars?

Several years back, I briefly observed a bright nova just outside the galaxy's nucleus in my 15-inch reflector when it peaked around magnitude +14.9. That was a lucky break as most novae in M31 max out around magnitude +17-19 and require telescopes upwards of 20-inches to track down.

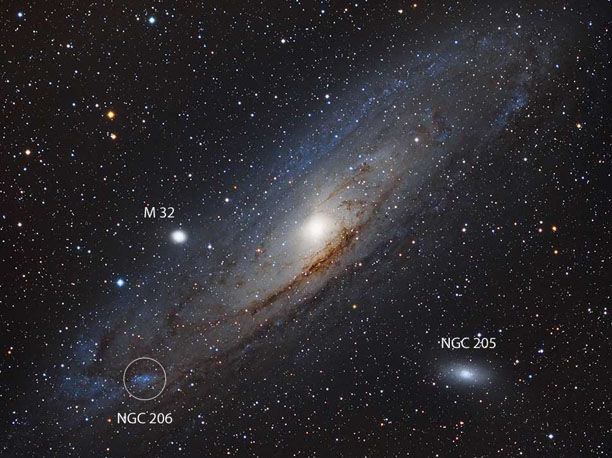

In this wide-field photo of the Andromeda Galaxy, the bright OB association NGC 206 resembles its visual appearance. The massive star cloud is located at the southwestern end of the galaxy's disk at the junction of two spiral arms.

Patrick Winkler / Online Photo Gallery

Patrick Winkler / Online Photo Gallery

Then one fall night, while hunting down globulars and other minute delights in the galaxy, I shifted the scope toNGC 206, M31's largest and brightest star cloud. The object, which resembles a weakly condensed 10th-magnitude comet superimposed on Andromeda's southwestern arm, measures 4.2′ across. Its true size is about 4,000 light-years across or nearly three times the distance from Earth to the star Deneb in the Northern Cross, making it one of the largest star clouds in the Local Group of galaxies.

If you haven't observed it yet, you've probably noticed this distinctive hazy patch in photos of Andromeda. NGC 206 also goes by the name OB 78 and resembles the vastPerseus OB 1 association which includes Mirfak, the brightest star in Perseus, and the popular Double Cluster.

OB associations, named after the brilliant class O and B stars they contain, are loosely organized gaggles of young stars and star clusters born in the collapse of a giant molecular cloud. True star clusters, more compact by nature, keep hold of their stars through gravitational attraction. Thinly spread OB associations make easy prey for galactic tides, which pull associations apart and disperse their members far and wide.

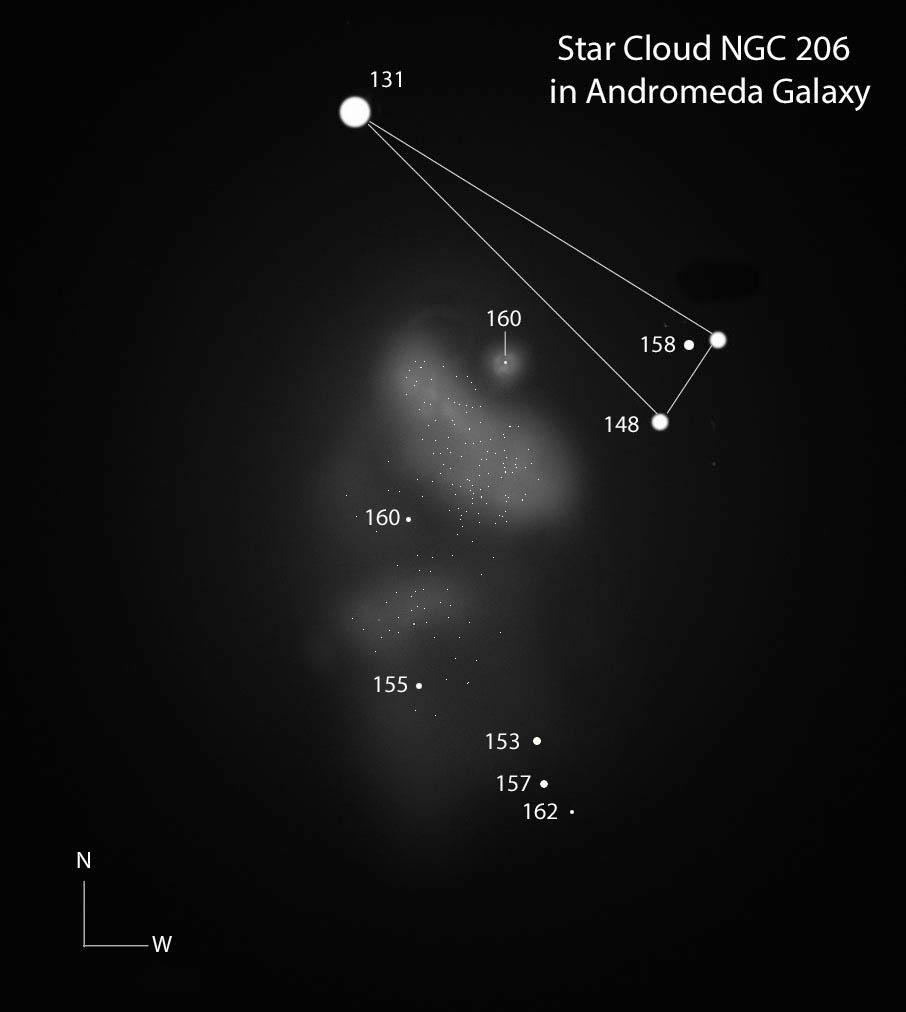

This closeup of NGC 206 reveals a rich gathering of hot blue supergiant stars. The cloud is similar in size to the spectacular Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud and NGC 604 in M33, the Pinwheel Galaxy. I've included a "triangle guide" here and in the sketch below to help you get oriented. North is up.

Michael A. Siniscalchi

Michael A. Siniscalchi

NGC 206 is home to some 300 brilliant blue stars, the youngest of which are just 10 million years old, incredibly young by stellar standards. Stars 20 times more massive than the Sun are common with a few topping out at more than 40x solar! Inspired by these superlatives and photos that showed good resolution of the cloud, I cranked up the magnification to 242x and then 357x, allowed my eyes to fully adapt to the darkened field of view and got the surprise of my life. Stars!

NGC 206 appeared in three sections: a tiny ~30″ wide knot dotted by a 16th magnitude star, a brighter, clumpy northern "cloud" and a fainter, more distended southern section separated by a relatively haze-free gap (in other words, no unresolved stars). Direct vision revealed several faint stellar points around and within the cluster, some of which were members of the association and not Milky Way foreground suns.

NGC 206 lies at the intersection of two of Andromeda's spiral arms and was likely spawned in a collision of massive dust clouds at their intersection.

Jim Misti

Jim Misti

But the thing that positively electrified the view was seeing OB 78 materialize into a rich spray of barely visible stars with averted vision. They came and went with the vagaries of my eye's position and seeing conditions, but there was no question I was seeing cluster stars based on location and star density compared to the ambient Milky Way foreground. The scene reminded me of the grainy interiors of the remote globular clusters NGC 7006 in Delphinus and the "Intergalactic Wanderer," NGC 2419, in Lynx.

In all three cases, it was next to impossible to hold so many faint stars in view long enough to see them individually or connect them into patterns. Instead, they appeared as a granulated haze or mist of dim points that flashed in and out of view.

Stephen Odewahn of the McDonald Observatory surveyed NGC 206 in the 1980s and published a photometric survey of its brightest stars. While most are hopelessly faint for visual observers even with moderately large telescopes, 14 members range between magnitude +14.8 and +17.5, making them somewhat less hopelessly faint.

A 15-inch scope covers the brighter end of that range with ease, but the number of stars I glimpsed with averted vision implies that in some situations, based on seeing, magnification and experience, we can momentarily best a telescope's limiting magnitude by a surprising margin.

This sketch of the NGC 206 star cloud was made primarily using a 15-inch telescope, but it's also informed by a view through a 24-inch. A skinny triangle of stars just north of the cloud will help you get oriented. Brighter stars are labeled with B (blue) magnitudes with decimal points omitted. All the stars, with the exception of the 13.1, are listed as association members in Odewahn's paper. The tiny stellar sprinkles are for illustration purposes and included to convey my impression when viewing the cloud.

Bob King

Bob King

No one should be content with a single observation of faint nothings, so I re-observed the star cloud on several occasions and confirmed my observation using friends' 18-inch and 24-inch telescopes. We invited several members of our clubs to view NGC 206 and every one of them was able to at least partially resolve the stellar association in each scope.

Using a photo labeled with some of the brighter stars fromOdewahn's paper, I was able to clearly see and identify seven stars between magnitudes +14.8 and +15.8 in the 15-inch. I've included these in a drawing made using Photoshop that I hope will provide a useful tracking guide for your own explorations.

While a 24-inch scope reveals even more stars, a 15-inch scope is easily up to the task of breaking out some of Andromeda's brightest blue supergiant stars from this magnificent clutch of stellar celebrities. Daring amateurs may even want to put a 10 or 12-inch scope to the task. I'd love to know what you'll see.

No comments:

Post a Comment