Astronomy - The Merope Nebula and Its Well-Kept Secret

Did you know that the brightest part of the Merope Nebula in the Pleiades is also the hardest to see? We'll make sense of this seeming contradiction while honing key observing skills.

The Pleiades reflection nebula, the brightest part of which surrounds the star Merope (lower center), is visible in 6-inch and larger telescopes.

Bob King

Bob King

By November, the Pleiades star cluster has climbed high enough in the eastern sky to be noticed by even most casual observer. Also known as the Seven Sisters, this mini-dipper of fuzzy jewels, all moving together through space, is 444 light-years from Earth.

The cluster is dominated by hot, intermediate-aged blue stars that light up the surrounding dust as a reflection nebula. Not so long ago, it was thought that the cotton candy-like tufts of nebulosity were left over from the formation of the cluster, but the 100-million-year age of its members precludes this possibility; stars that "old" would have swept out any remaining embryonic dust long ago.

Instead, the Pleiades just happen to be passing through a dust-rich region of the interstellar medium as they make a beeline for Orion. Picture a flashlight beam moving through a fog of varying thickness, its light revealing textures and densities that change from moment to moment. In this new view of the Seven Sisters, we can imagine our distant descendants looking at a rather different nebula that the one we see.

The hot blue stars of the Pleiades star cluster happen to illuminate a large cloud of interstellar dust along the cluster's path. The group is moving toward the southeast at 5.5″ per century. Click for a large version.

Davide De Martin & the ESA / ESO / NASA Photoshop FITS Liberator

Davide De Martin & the ESA / ESO / NASA Photoshop FITS Liberator

Visually, glare from all these gorgeous blue suns makes it difficult to tell the nebula from the oft-seen glowing aureoles around bright stars. And if your optics are dirty, it's even more challenging. But the Merope Nebula, the brightest and most extensive swish of glowing dust in the cluster, is visible in even a 6-inch telescope at low to medium magnification (25×–100×). Take care to place 4th-magnitude Merope just outside the field of view for the best view.

The Merope Nebula has an attractive teardrop shape readily visible in a smaller instrument. Keep Merope (above center) out of the field of view. North is up.

Hap Griffin

Hap Griffin

I'm reminded of breath on a mirror when viewing the Merope Nebula. Maybe breath on the eyepiece paints a more accurate picture, since nights can be cold in November and observers must take care not to accidentally breathe on a lens! The larger your scope, the more obvious the nebula, but it's best on the low magnification end — an island of cosmic dust with Merope a beacon blazing along its northern shore.

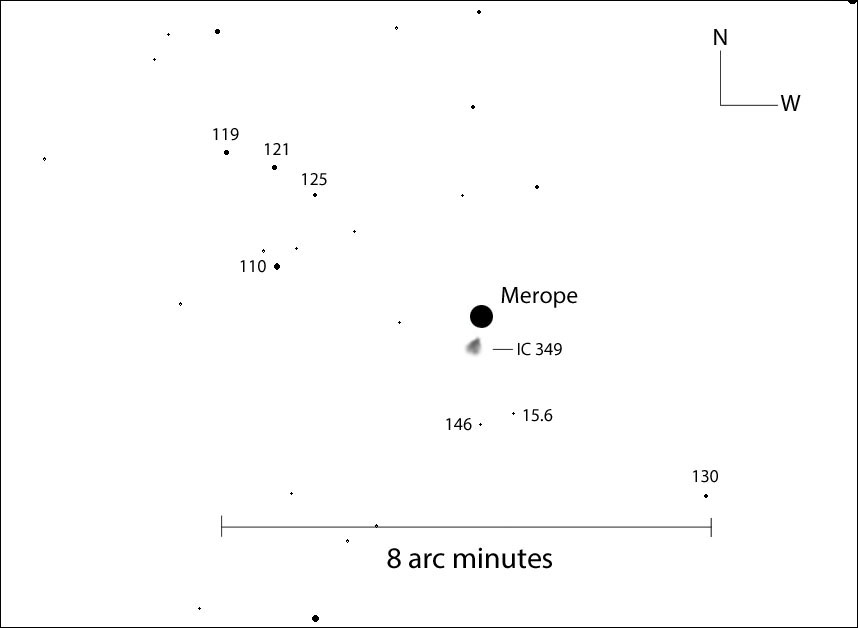

Use this chart to help you pinpoint Barnard's Nebula about 30″ southeast of 4th-magnitude Merope. Field stars' magnitudes are shown with decimals omitted. Click for a larger version to print out for use at the telescope.

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

Not to be confused with the larger, much easier to see Merope Nebula is her well-hidden sister, Barnard's Merope Nebula. This tiny 10″ patch was discovered by American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard in 1890 using the 36-inch Lick refractor. Although 15 times brighter than the Merope Nebula proper, it's incredibly hard to spot in the fierce glare of nearby Merope, blazing only 36″ to the northwest. Here's what E. E. had to say when he first saw it:

"... discovered a new comparatively bright, round cometary nebula close south and following Merope (23 Tauri) ... It is about 30″ in diameter, of the 13 (magnitude), gradually brighter in the middle, and very cometary in appearance."

He went on further to note that it was no surprise such a bright nebula hadn't been photographed before, since an exposure to capture the fainter parts of the Pleiades nebulosity would overexpose this nebular nubbin.

This object, also cataloged as IC 349, is one of the most challenging objects I've ever attempted to see. If it weren't for the glare of Merope, it would be far better known. In a wicked irony, the very thing that makes it the brightest part of the Pleiades nebula also thwarts its visibility.

Compare the photo of IC 349 taken with the Hubble Space Telescope (left) to an image taken through an amateur telescope. The bizarre appearance of the nebula is cause by radiation pressure from Merope. Smaller particles pushed away by the pressure of starlight gather to the lower left, while larger particles point toward the star, which is moving toward the nebula. Click photo to see a larger Hubble image.

Left: NASA / ESA, Right: Volker Wendel, Josef Pöpsel, Stefan Binnewies: www.capella-observatory.com

Left: NASA / ESA, Right: Volker Wendel, Josef Pöpsel, Stefan Binnewies: www.capella-observatory.com

On a recent night of above average seeing, I cranked up the magnification on my 15-inch Dob reflector to 428× to separate the nebula from the star as much as possible. Then I placed Merope just outside the field of view. After more than a half hour of averted vision viewing, during which time I repeatedly re-hid the drifting star, I strongly suspected a dab of nebulosity between Merope's flashing diffraction spikes and within its glowing aureole. The effort made me hungry enough to eat a steak.

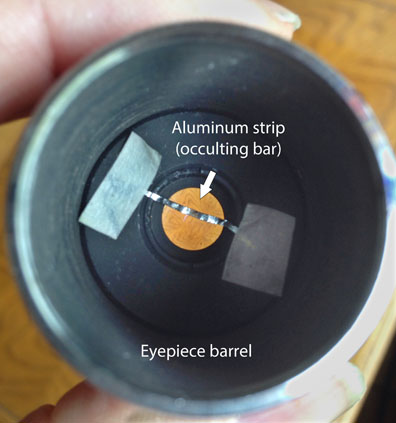

To make an occulting bar, slice a narrow strip of aluminum foil and tape it over the field stop of an eyepiece. You may have to use a toothpick to bend / push the strip into the focal plane, so it comes to a sharp focus when viewed through the eye lens.

Bob King

Bob King

At the next opportunity, I opted to use an occulting bar instead. I taped a thin strip of aluminum foil across the field stop of an old 12-mm Orthoscopic eyepiece and plunked it into a 2× Barlow for a magnification of 284×. After noting the direction of Merope's drift across the field, I aligned the opaque bar to hide the star and suppress its glare.

This is the preferred arrangement for spotting faint objects near bright ones. It works wonders when hunting the satellites of Uranus or attempting to see the white dwarf companion of Sirius.

Seeing wasn't nearly as good as the previous night's, but once again, I strongly suspected a cometary patch at the correct position. I've also attempted observations of the nebula in the past but never came away 100% convinced of seeing it. Until my suspicion becomes a confirmation, this tough nut will remain on my observing list!

The main Merope Nebula resembles streaks of cirrus clouds crossing the sun in this close up view. The little blip sticking out below Merope is Barnard's Nebula, IC 349.

Hunter Wilson

Hunter Wilson

Since visual observations are almost non-existent, I can't say what the minimum-size aperture would be required to see this mini-Merope but suspect that clean, well-collimated optics and steady seeing will play important roles in your attempt. I strongly encourage observers with 8-inch and larger scopes to try this one out. There's no better time than late fall and winter when the Pleiades extend an invite every moonless night.

No comments:

Post a Comment