Astronomy - Uranus: In Seventh Heaven with Planet Seven

With our eyes often glued to the bright classical planets, Uranus is easy to overlook. Now that it's well-placed for viewing at a convenient hour, why not pay this pale blue dot a visit the next clear night?

Like the late comedian Rodney Dangerfield, Uranus gets no respect. It starts with its name, which if pronounced yoo-RAY-nuss (a.k.a. Your-ANUS), draws knowing looks even from a polite planetarium crowd. Teachers and lecturers often sidestep the whole uncomfortable business and instead say YUR-in-nuss or even yoo-RAH-nuss.

As a youth I said yoo-RAY-nuss at will and no one blinked an eye. Much later, I switched over to the more delicate pronunciation for shows and speaking engagements. But the devil-may-care in me doesn't feel like padding around on eggshells anymore, so now I let the old-style Uranus fly.

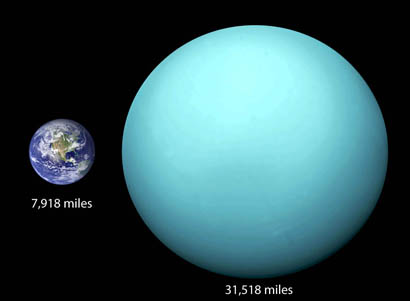

Of course, none of this has anything to do with the real planet, a chillingly remote and blue world. That's how it looked on Supermoon Sunday when a fellow amateur invited me to look at the dot-sized world through his scope. Its color derives from atmospheric methane that absorbs the warmer colors of the spectrum and reflects back a gorgeous shade of aquamarine.

William Herschel discovered Uranus in 1781. Lemuel Francis Abbott painted this portrait of the famous observer four years later.

The planet, seventh from the Sun, is remarkable for several reasons. Six and only six classical planets had been known since the dawn of human history until amateur astronomer William Herschel stumbled upon the seventh with a 6.2-inch f/13 reflector of his own making on March 13, 1781. He was 42 years old at the time and was spending his nights examining every bright star to see if it was double. Astronomers hoped that by observing closely-spaced stars over time, they could measure a shift in their positions called parallax, and use those shifts to determine the stars' distances from Earth.

To distinguish double from single stars, Herschel used high magnification; a power of 227× generally sufficed. That's how he noticed that one particular bright "star" in Taurus showed as a disk instead of a point. Since he wasn't expecting a planet, Herschel at first reported it as a comet. But continued observation revealed otherwise, and the rest is history.

Stellar parallaxes would elude astronomers for another 57 years until Friedrich Bessel calculated the distance to 61 Cygni in 1838. But as in many scientific endeavors, the sieving of one type of data caught something unexpected. Herschel had the eye and presence of mind to stop and pay attention to his oddball star, leading to a monumental moment — the first new planet discovered since antiquity.

While 60× will suffice to see Uranus as a disk, I prefer Herschel's 227× if only to see it the way he did for the first time on that late winter night from his garden on 19 New King Street in Bath, England. Magnifications of 200× and up show it as perfect, pale blue dot about 3.5″ across. Earth must look a similar color when viewed from afar.

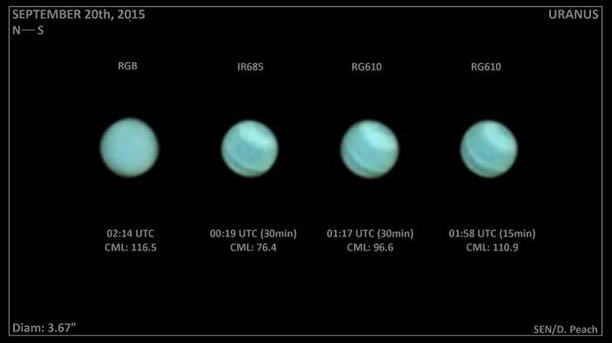

The belts of Uranus are visible in this series of photos taken in September 2015 with RGB, infrared (IR), and near-infrared filters.

SEN / Damian Peach

SEN / Damian Peach

Many observers see little more than a featureless disk through the telescope. But careful study with 8-inch and larger scopes at magnifications in excess of 300× on nights of superb seeing have yielded pay dirt for some, revealing faint parallel bands on either side of a brighter equatorial zone during the best moments.

The mind's eye does better when picturing the planet's weird sideways rotation, 13 rings, 27 moons, an atmosphere colder than more distant Neptune's (down to –371° F / –224° C in some places), winds up to 560 mph (900 km/h), and a sloshy interior of water, methane, and ammonia ices under tremendous pressure.

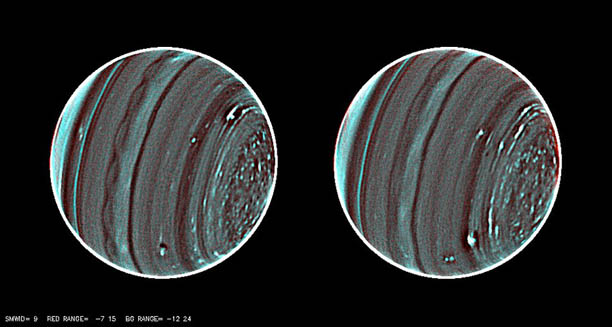

Uranus is visually featureless in most amateur telescopes. However, in these images — the most detailed ever taken — the cloudy stripes are evident. Taken in near-infrared light with one of the 10-meter Keck telescopes in 2012, these photos were created by averaging 100 individual images. North pole is on the right in both views.

Larry Sromovsky and Pat Fry (Space Science and Engineering Center, UW-Madison) / Heidi Hammel (Space Science Institute, Boulder, CO) / Imke de Pater (UC Berkeley)

Larry Sromovsky and Pat Fry (Space Science and Engineering Center, UW-Madison) / Heidi Hammel (Space Science Institute, Boulder, CO) / Imke de Pater (UC Berkeley)

Uranus's cloudy exterior is striped with faint bands that resemble those on Jupiter and Saturn, but they're exceedingly difficult to see and best revealed photographically using a near-infrared filter to increase their contrast. Still, the planet offers two delightful observing challenges, one for the naked eye and the other for telescope users.

Uranus is located in eastern Pisces, a fist west of Alpha (α) Piscium between the 5th-magnitude stars Mu (μ) and Zeta (ζ). Shoot a line through Beta (β) and Alpha Pegasi to Delta (δ) Piscium. Uranus is the 4th "star" in a row to the east of Delta.

Stellarium

Stellarium

Seeing Uranus without optical aid isn't too difficult, especially in November with the planet just a month past opposition and crossing the meridian around 9 o'clock. At magnitude +5.7, it's a smidge brighter than the traditional 6th-magnitude limit of visibility, which many an amateur knows can be pushed to +6.5 or even deeper under exceptional skies. With a good map, you can nail down exactly where to look. Now through the end of the year, Uranus takes a position in a dance line of Greek alphabet stars in eastern Pisces.

You can use this map with binoculars or a telescope. Tick marks are at 10-day intervals through early 2017. Stars are shown to magnitude +7.5 and north is up. "88" is 88 Piscium.

Chris Marriott's SkyMap software

Chris Marriott's SkyMap software

Once you know where to look, scan around the spot with averted vision and watch the faint planet pop into view. Now think of how many millions of times our ancestors unknowingly stared right at it ... and moved on. Even with the advantage of near-zero light pollution, it evaded every gaze until Mr. H got to work.

If your sky won't allow a naked-eye attempt, binoculars will show the planet with ease and even allow you to track its westward retrograde motion into late December.

A near-infrared view of Uranus with seven of its moons taken with the Very Large Telescope in northern Chile in 2002. Its ring system is also plainly visible.

ESO

ESO

Another Uranian challenge is to seek out its five brightest moons: Titania (magnitude +13.8), Oberon (+14.0), Ariel (+14.1), Umbriel (+14.8) and Miranda (+15.8). Titania and Oberon look like fly specks in the planet's glaring aureole; an 8-inch or 10-inch scope should bring them to light. Use a magnification of at least 225× and averted vision. If you make an occulting bar for your eyepiece to block the planet's glare, you'll be amazed at how much easier they are to see.

Uranus and its five brightest moons are shown for this evening, November 16th. The two brightest satellites, Titania and Oberon, are near greatest southern elongation, one of the best times to find them. Right: The planet's orientation in 2016.

Left: Sky & Telescope; Right: Bob King

Left: Sky & Telescope; Right: Bob King

Ariel and Umbriel are not only fainter but much closer to the planet. While I've spotted both Titania and Oberon in my 10-inch and 15-inch telescopes, Ariel and Umbriel remained hidden until this summer when I finally extracted them from the glare in a friend's 24-inch reflecting telescope. For a few minutes, Uranus had that "Solar System in miniature" look. Miranda is closer yet and much fainter. I've never seen it. You?

To know exactly where to look for the Uranian moons, useSky &Telescope's handy Uranus Moon Finder. No matter how you pronounce it, Uranus will keep you company during the dark nights ahead, when other classical planets have slipped into bed.

No comments:

Post a Comment