India Launches First Astronomy Satellite

AstroSat launched into orbit on September 28, 2015, and will soon start returning visible, ultraviolet, and X-ray images of the universe.

Indian astrophysics got a boost recently when an Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) PSLV rocket launched from Satish Dhawan Space Center on September 28th, placing Astrosat in a low-Earth orbit inclined 6° to the equator. The multi-purpose observatory is equipped to observe the Universe across the X-ray spectrum, accompanied by simultaneous visible and ultraviolet light observations.

Previously, India has lofted X-ray detectors aboard high-altitude balloons and sub-orbital sounding rockets, but this is India’s first astronomical satellite. Data from AstroSat will be available to the Indian astronomy community via proposals for observations.

“Expectations naturally depend on the aspirations of the astronomer,” says payload manager Arikkala Raghurama Rao (Tata Institute of Fundamental Research). “Personally, I expect Astrosat to break new ground in understanding the jet emission from black holes (stellar-mass as well as supermassive black holes), the beaming geometry of pulsars, and extending the observations of short gamma-ray bursts to higher redshifts.”

With the capability of observing from visible wavelengths all the way through high-energy X-rays, Astrosat will also be capable of studying everything from nearby white dwarfs, pulsars, and supernova remnants to faraway galaxy clusters.

From Visible Light to X-rays

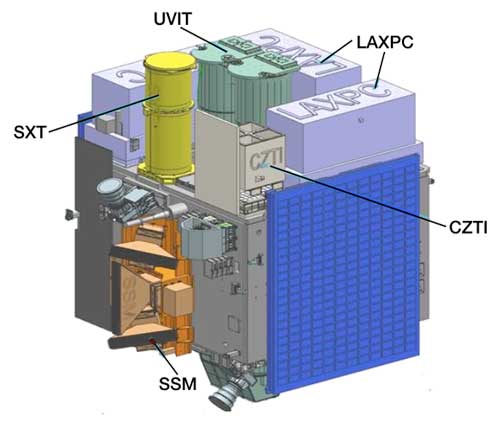

Astrosat carries five astronomical instruments that observe the sky in five different wavelength ranges, from visible through near- and far-ultraviolet, to low-energy and high-energy X-rays.

- The Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (UVIT) is a twin optical system, each primary mirror 37.5 centimeters in diameter and in a Ritchey-Chrétien configuration. Think of the UVIT payload as a set of binoculars in space, with each ocular about twice the size of a backyard 8-inch diameter Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope. The primary purpose of this instrument is to accompany X-ray observations with simultaneous visible, near-, and far-ultraviolet images, covering 130 to 530 nanometers.

- The Soft X-ray Telescope (SXT) focuses “soft” X-rays (that is, low-energy X-rays between 300 and 8,000 electron Volts) into images from which low-resolution spectra can also be extracted. Its design is similar to the Swift’s X-ray Telescope.

- The Large Area Xenon Proportional Counters (LAXPC) are three block-shaped detectors that collect X-rays with higher energies, between 3,000 and 80,000 eV. Unlike the SXT, this instrument doesn’t focus X-rays into images, but it does provide incredibly precise arrival times for each photon. Astronomers can also reconstruct low-resolution spectra from the data LAXPC collects.

- The Cadmium-Zinc-Telluride Imager (CZTI) collects X-ray photons with even higher energies, up to 150,000 eV. While it also doesn’t focus X-rays, this instrument can carry out polarization measurements, a capability lacking on most other X-ray telescopes.

- The Scanning Sky Monitor (SSM), a detector with a huge 10° by 90° field of view, which will scan the sky for transient X-ray sources. Its design is much like the decommissioned Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer (RXTE).

Another auxiliary payload aboard Astrosat is a Charged Particle Monitor (CPM), which counts charged particles to protect the satellite’s instruments, particularly when the spacecraft passes through the South Atlantic Anomaly region, an area of high electron and proton flux.

New Capabilities

AstroSat in the clean room. The triple tubes are the SXT and two UVIT detectors, while the three boxes stowed around them are the LAXPC.

ISRO

ISRO

Astrosat joins several other X-ray observatories already in orbit: Chandra makes out fine details in low-energy X-ray images, NuSTAR brings high-energy X-rays into sharp focus, Swift monitors the sky for distant explosions bright in X-rays and gamma rays, and the European Space Agency’s (ESA) XMM-Newton is a light bucket that can measure X-ray spectra of faint sources. So what does Astrosat bring to the table?

Kulinder Pal Singh (Tata Institute for Fundamental Research) compares Astrosat to a combination of the Swift satellite and the now-retired Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer satellite (RXTE). Like Swift, Astrosat will hunt for X-ray transients and observe these sources across the visible-to-X-ray spectrum. And like RXTE, LAXPC’s triplet of detectors will measure the arrival time of each photon. LAXPC has the largest collecting area of any X-ray instrument ever built, and it’s currently the only one capable of studying X-ray fluctuations over millisecond timescales.

The satellite is now undergoing systems checks: the CPM and CZTI are now operational, and Singh says we can expect to see Astrosat’s first images about 6 to 8 weeks post-launch. The satellite has an expected lifetime of at least five years.

By the way, NORAD cataloged Astrosat as ID 2015-052A/40930 shortly after launch, but unfortunately for northern satellite spotters, Astrosat’s low-inclination orbit makes it visible only from Earth’s equatorial regions due to its low inclination orbit.

The Indian Space Research Organization has proven itself a force to be reckoned with thanks to recent success stories, including the Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter and the Mars Orbiter Mission, which successfully entered orbit around the Red Planet on September 24, 2014. (It’s worth noting that India is the only nation that was successful in fielding a mission to Mars on its first try!)

Now we can add Astrosat to India’s list of space success stories, one that holds a promise of some exciting astrophysics discoveries to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment