Mars Gravity Map

By tracking deviations in spacecraft orbits, planetary scientists have created a high-resolution map of the Red Planet's gravitational pull.

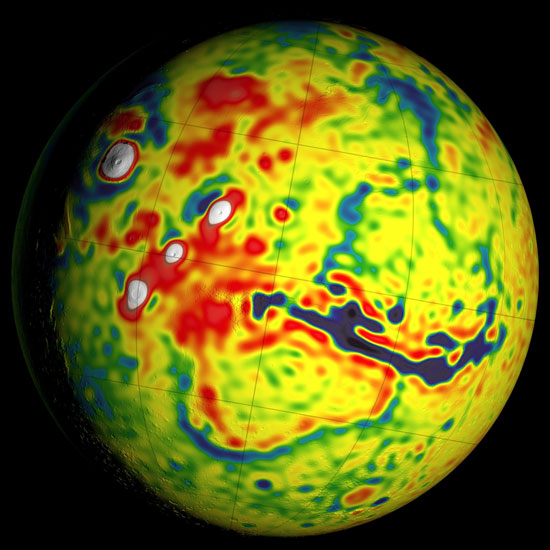

If you could see past Mars’s surface to how its gravity changes from place to place, what you’d see is this:

This map shows local variations in Mars's gravitational pull on orbiters. The view is centered at 90 degrees west longitude, showing the four volcanoes of the Tharsis region (white dots) and the deep Valles Marineris canyon system just right of center (dark blue gash). The color coding is in units of gravity acceleration variability, called gals or galileos. The range is from about half a negative gal (dark blue) to one positive gal (white).

NASA / GSFC / Scientific Visualization Studio

NASA / GSFC / Scientific Visualization Studio

This map isn’t a topographic map, which shows terrain elevations. It’s a gravity field map. Essentially, it’s a look at the planet’s skeleton. What it shows is how strongly or weakly different parts of Mars tug on orbiting spacecraft. Antonio Genova (MIT and NASA) and others constructed the map using about 16 years’ worth of combined tracking data for three spacecraft: Mars Global Surveyor (operated 1999 to 2006), 2001 Mars Odyssey (2001 to present), and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (2006 to present).

Prolonged, careful analysis enabled the team to pull insights out of the gravity data. For example, the team could detect tides in the Red Planet — yes, even though there are no oceans — created by the Sun as well as Mars’s moon Phobos (smaller, more distant Deimos has a negligible effect). The tidal stretching and squeezing confirm that the planet’s outer core isn’t entirely solid; the outermost edges are still molten. Charles Yoder (JPL) and others found the same thing back in 2003 using tracking data for Mars Global Surveyor.

Scientists think that a global magnetic field arises due to convection in a conducting, liquid-metallic core, spurred by heat flowing outward from core to mantle. Mars’s global field shut down about 4 billion years ago. The team isn’t at the point where they can answer why Mars’s field is dead, Genova says, but one explanation is that the fluid outer core is now too thin to create a global field.

Even the atmosphere’s seasonal migration affects the planet’s gravity field. Itsy-bitsy changes in the spacecraft’s orbits suggest that when winter hits the southern hemisphere, about 4 trillion tons of carbon dioxide freeze out of the atmosphere onto the southern polar cap. (It’s about 3 trillion for the northern cap.) That’s roughly 15% of the mass of the entire Martian atmosphere, as explained in NASA and JPL’s joint press release.

There’s also the matter of a “gravity trough” that lies between Acidalia Planitia (part of the wide northern lowlands) and the higher terrain of Tempe Terra. Previously, scientists thought this trough was some sort of buried channel system that once carried muddy water from the highlands into the basin. But the new analysis shows that the trough covers a lot more area and seems to ring the northern highlands’ edge even down close to the equator. Plus, the only drainage channels in sight run across it perpendicularly, not with it. So the team suggests that instead this feature is some kind of moat, created when the gigantic volcanoes of the Tharsis region built up their surrounding plateau so much that the crust beneath buckled under the weight. (The effect is more noticeable in this projection of the gravity map from NASA.)

The team’s paper appears in the July 1st Icarus. NASA Goddard’s Scientific Visualization Studio also put out a nice video summary of the results, which I’ve embedded below.

No comments:

Post a Comment