Astronomy - Did Ancient Explosions Rock Eta Carinae?

New observations suggest this unstable star let off some steam before its famous 19th century “Great Eruption.”

The Hubble Space Telescope has been keeping an eye on Eta Carinae since 1993. The Homonculus Nebula seen here hides two stars on a tight, oval-shaped orbit within.

Nathan Smith / Jon Morse / NASA

Nathan Smith / Jon Morse / NASA

In 1843 the giant, unstable star known as Eta Carinae began shedding its outer layers, ultimately expelling at least 10 Suns’ worth of gas. That is roughly 10% of the star’s total estimated mass. The star brightened from obscurity to become the second-brightest star in the sky before fading away again to the limit of the naked eye.

Needless to say astronomers took notice, and ever since then they’ve been trying to explain this star’s sudden and mysterious violence. Sky & Telescope recently provided an overview of recent research on Eta Carinae — check out Keith Cooper’s feature article in the October 2016 issue on newsstands now — but now there’s one more surprise to add: the possibility of explosions before the famous Great Eruption of the 19th century.

Ancient Eruptions?

In Eta Carinae's core two massive stars orbit each other, coming within about 1½ astronomical units of each other every 5½ years. This frame comes from a computer simulation of the stars' orbits and shows their interacting stellar winds.

NASA / Goddard Space Flight Center / T. Madura

NASA / Goddard Space Flight Center / T. Madura

Eta Carinae lies hidden behind the gigantic, still-expanding Homunculus Nebula, a double-lobed mass created during the Great Eruption. Yet astronomers are certain the star cloaked within isn’t alone. Its stellar companion weighs in at 30 solar masses and orbits the primary every 5.5 years in an oval-shaped orbit. Perhaps, some astronomers theorize, there may even have been a third star, which met an untimely death when it plunged into the primary star and brought about the 19th century explosion.

To peer deeper into this mysterious system, astronomers have been monitoring Eta Carinae for years. The Hubble Space Telescope, for one, has been keeping an eye on Eta Car since 1993, with the most recent observation taken in 2014. Megan Kiminki (University of Arizona) and colleagues are taking advantage of Hubble’s persistence to watch the star’s ejected gas fly outward in real time.

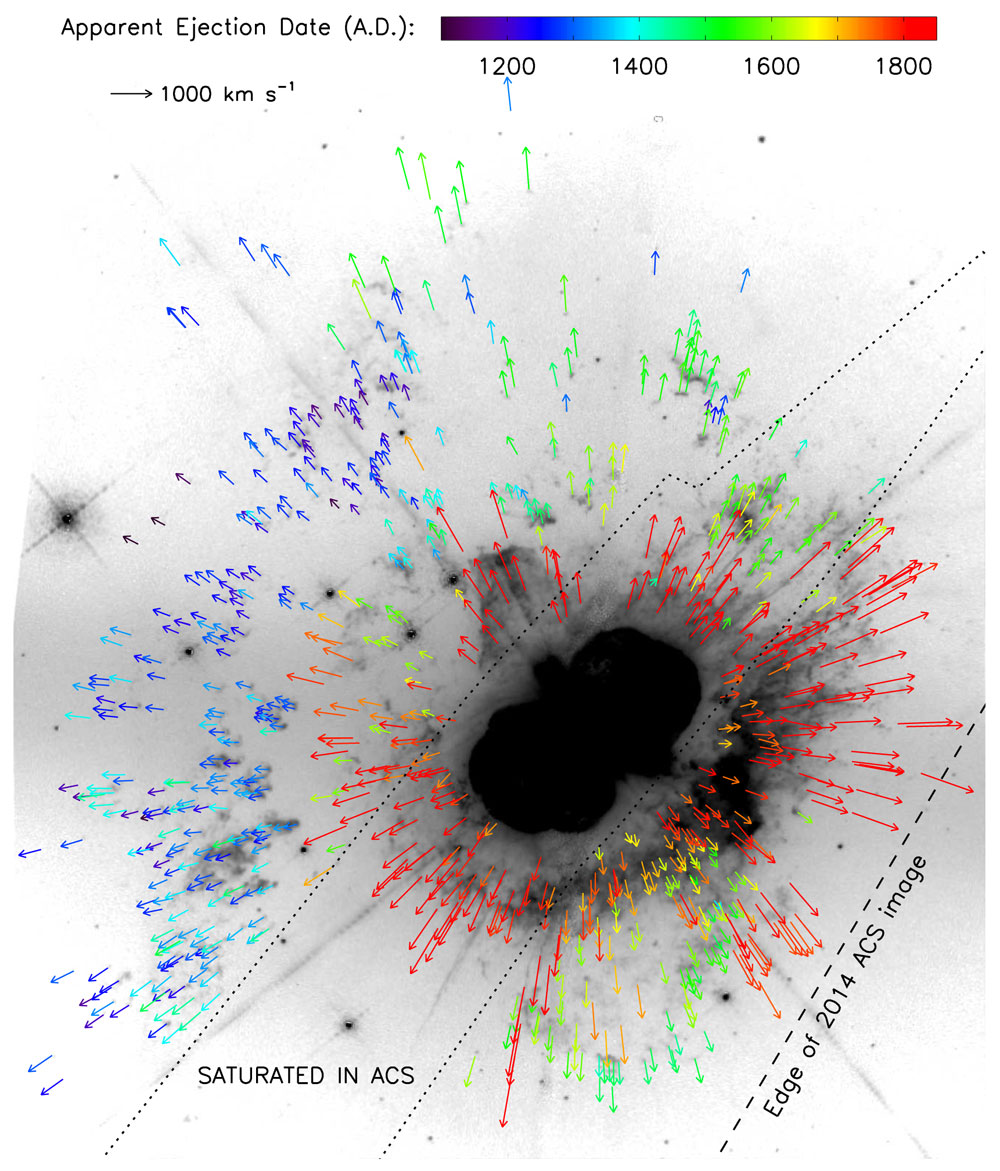

Kiminki’s team is studying the proper motions of gaseous clumps at the periphery of the Homunculus, measuring the clumps’ motion across the sky. Combining this information with spectra, which reveal motion toward or away from Earth, gives us the clumps’ three-dimensional movement in space.

Unsurprisingly, the team finds that the ejecta are flying away from Eta Carinae at hundreds, and in some cases more than 1,000, kilometers per second (2 million mph). What is surprising, though, is that if all the ejected clumps have always been traveling at the same speed, then they can’t have all come from the Homunculus-creating event: one, or perhaps two, eruptions went off before the 19th century.

Hubble imaged Eta Carinae in 2014 (shown in reverse color). To best see the faint clumps of gas at the outskirts of the nebula, the Hubble images have least 9 minutes of exposure time per image, which saturates the Homunculus Nebula at the center of the frame. The arrows show how fast each clump is moving through space, and the arrows are color-coded by the year of their ejection, calculated as if they have always traveled at the same speeds they're traveling now.

Kiminki & others, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Kiminki & others, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

The more likely eruption may have occurred around AD 1250, just before Marco Polo's first visit to the Court of Kubla Khan. The other ejection would have happened in AD 1550, just after Copernicus published his De Revolutionibus.

Ifs, Ands, or Buts

But constant speeds for outward-flung ejecta are far from a sure thing. For example, it’s possible that the incredibly fast wind now coming from the secondary star also existed in ancient times, whipping the clumps to higher speeds early on. If the constant-velocity assumption is untrue, then the theory of multiple outbursts stands on shaky ground.

“I'm open to the possibility of earlier eruptions if that is what the observations really tell us, but I am not 100% convinced yet,” says Thomas Madura (San Jose State University).

Another oddity: the gas clumps supposedly ejected in the thirteenth century lie entirely on the northeast side of the system, traveling toward Earth at an angle of 20-40° out of the plane of the sky. There’s nothing similar on the star’s west side.

“It seems curious to me that if there were another major eruption in the 1200s, it would be so extremely asymmetric,” Madura adds. “This could perhaps be a sign that the mechanisms for each eruption were drastically different.”

Understanding those mechanisms is difficult in part because there’s no firm estimate of the mass ejected in ancient times. If Eta Carinae experienced earlier explosions before the Great Eruption, that leaves astronomers once again with the question: what caused Eta Carinae to blast away its outer layers without going whole hog supernova? And if the star is so unstable, why is it still here?

“I'm sure we'll still learn a lot about the late stages of massive star evolution by continuing to study [Eta Carinae],” Madura says. “It has a habit of surprising us.”.

No comments:

Post a Comment