Dark Dwarf Galaxy Discovered

Astronomers using the ALMA array of radio dishes have detected a dwarf galaxy 4 billion light-years away by the pull of its dark matter.

A long time ago around a galaxy far, far away, a dwarf galaxy awaited discovery. This miniature galaxy is almost entirely dark matter dominated — it contains few, if any stars. Only by combining the power of dozens of radio dishes high in the Atacama Desert in Chile could astronomers spot the dark dwarf’s gravitational mark.

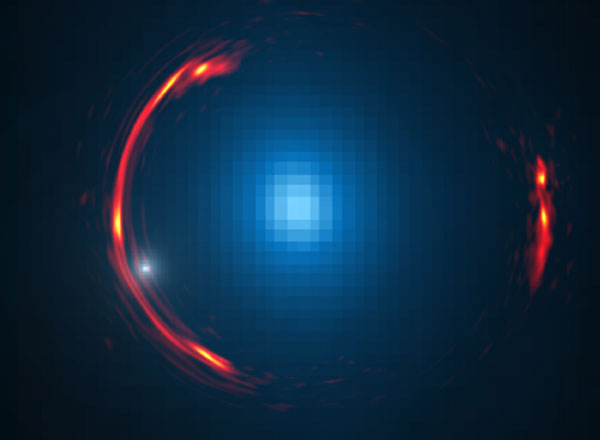

This composite image of the gravitational lens SDP.81 shows the distorted light from a distant background galaxy (red, imaged by ALMA) and the nearby elliptical galaxy that's doing the lensing (blue, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope). The white dot near the left lower arc segment indicates the location of a dark dwarf galaxy. Although it doesn't emit observable light itself, the dwarf's mass nevertheless produces effects in the distorted image of the background galaxy.

Y. Hezaveh (Stanford Univ.) / ALMA (NRAO / ESO / NAOJ) / NASA / ESA / Hubble Space Telescope

Y. Hezaveh (Stanford Univ.) / ALMA (NRAO / ESO / NAOJ) / NASA / ESA / Hubble Space Telescope

About a year ago, a team of astronomers imaged a tiny ring in the sky just 3 arcseconds across. This ring was actually the gravitational distortion of light from a distant background galaxy. A massive elliptical much closer to Earth, dubbed SDP.81, acted as a gravitational lens, bending the background galaxy’s light into a circle.

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) imaged this ring in stunning detail, one of the first ultrasharp images to be collected using the array’s longest 15-kilometer baseline. (Read “Ring-Shaped Spyglass to Early Universe” for more information on the original image.)

Now another team, led by Yashar Hezaveh (Stanford University), has employed the Blue Waters supercomputer to analyze the same set of data — and to make a surprising discovery.

Hidden within the depths of the background galaxy’s distorted image, Hezaveh and colleagues have found the unmistakable signature of a dwarf galaxy with the mass of a billion Suns. The dwarf, which orbits the massive lensing galaxy SDP.81 — not the more distant galaxy — made its presence known by its additional, subtle distortion of the background galaxy’s light. Hezaveh’s team also found hints of even smaller dark matter clumps floating in SDP.81’s halo.

All together, the clumps of dark matter around SDP.81 match what’s expected from simulations modeling the evolution of the universe in the presence of dark matter. That’s something of a surprise considering that the number of dwarfs found around the Milky Way is much lower than those models predict, the so-called missing satellite problem. Then again, astronomers still depend on light to detect diminutive galaxies around our own — it's likely that they’re missing dark galaxies that emit little if any light, and they're already well on their way to upping the tally to a more comfortable number.

In a press release, team member Joaquin Vieira (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) hailed the discovery as “the most sensitive picture of dark matter ever.” The international collaboration is already looking forward to applying their novel technique elsewhere, on the hunt for dwarfs around other gravitational-lens galaxies.

No comments:

Post a Comment