Viral Hepatitis - Background, pathophysiology and prognosis

Background:

Hepatitis, a general term referring to inflammation of the liver, may result from various causes, both infectious (ie, viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic organisms) and noninfectious (eg, alcohol, drugs, autoimmune diseases, and metabolic diseases); this article focuses on viral hepatitis, which accounts for more than 50% of cases of acute hepatitis in the United States.

In the United States, viral hepatitis is most commonly caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV),hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus(HCV). These 3 viruses can all result in acute disease with symptoms of nausea, abdominal pain, fatigue, malaise, and jaundice.[1]Additionally, HBV and HCV can lead to chronic infection. Patients who are chronically infected may go on to develop cirrhosis andhepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).[1]Furthermore, chronic hepatitis carriers remain infectious and may transmit the disease for many years.[2]

Other hepatotropic viruses known to cause hepatitis include hepatitis D virus (HDV) andhepatitis E virus (HEV). However, the term hepatotropic is itself a misnomer. Infections with hepatitis viruses, especially HBV and HBC, have been associated with a wide variety of extrahepatic manifestations. Infrequent causes of viral hepatitis include adenovirus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and, rarely, herpes simplex virus (HSV). Other pathogens (eg, virus SEN-V) may account for additional cases of non-A/non-E hepatitis.

Acute versus chronic viral hepatitis

The term viral hepatitis can describe either a clinical illness or the histologic findings associated with the disease. Acute infection with a hepatitis virus may result in conditions ranging from subclinical disease to self-limited symptomatic disease to fulminant hepatic failure. Adults with acute hepatitis A or B are usually symptomatic. Persons with acute hepatitis C may be either symptomatic or asymptomatic (ie, subclinical).

Typical symptoms of acute hepatitis are fatigue, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Very high aminotransferase values (>1000 U/L) andhyperbilirubinemia are often observed. Severe cases of acute hepatitis may progress rapidly to acute liver failure, marked by poor hepatic synthetic function. This is often defined as a prothrombin time (PT) of 16 seconds or an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5 in the absence of previous liver disease.

Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is defined as acute liver failure that is complicated by hepatic encephalopathy. In contrast to the encephalopathy associated with cirrhosis, the encephalopathy of FHF is attributed to increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier and to impaired osmoregulation in the brain, which leads to brain-cell swelling. The resulting brain edema is a potentially fatal complication of fulminant hepatic failure.

FHF may occur in as many as 1% of cases of acute hepatitis due to hepatitis A or B. Hepatitis E is a common cause in Asia; whether hepatitis C is a cause remains controversial. Although FHF may resolve, more than half of all cases result in death unless liver transplantation is performed in time.

Providing that acute viral hepatitis does not progress to FHF, many cases resolve over a period of days, weeks, or months. Alternatively, acute viral hepatitis may evolve into chronic hepatitis. Hepatitis A and hepatitis E never progress to chronic hepatitis, either clinically or histologically.

Histologic evolution to chronic hepatitis can be demonstrated in approximately 90-95% of cases of acute hepatitis B in neonates, 5% of cases of acute hepatitis B in adults, and as many as 85% of cases of acute hepatitis C. Some patients with chronic hepatitis remain asymptomatic for their entire lives. Other patients report fatigue (ranging from mild to severe) and dyspepsia.

Approximately 20% of patients with chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis C eventually developcirrhosis, as evidenced by the histologic changes of severe fibrosis and nodular regeneration. Although some patients with cirrhosis are asymptomatic, others develop life-threatening complications. The clinical illnesses of chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis may take months, years, or decades to evolve.

Pathophysiology

Hepatitis A

The incubation period of HAV is 15-45 days (average, 4 weeks). The virus is excreted in stool during the first few weeks of infection, before the onset of symptoms. Young children who are infected with HAV usually remain asymptomatic. Acute hepatitis A is more severe and has higher mortality in adults than in children. The explanation for this is unknown.

Typical cases of acute HAV infection are marked by several weeks of malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and elevated aminotransferase levels. Jaundice develops in more severe cases. Some patients experience a cholestatic hepatitis, marked by the development of an elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level, in contrast to the classic picture of elevated aminotransferase levels. Other patients may experience several relapses during the course of a year. Less than 1% of cases result in FHF. HAV infection does not persist and does not lead to chronic hepatitis.

Hepatitis B

HBV may be directly cytopathic to hepatocytes. However, immune system–mediated cytotoxicity plays a predominant role in causing liver damage. The immune assault is driven by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I–restricted CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes that recognize hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) on the cell membranes of infected hepatocytes.

Acute

The incubation period of HBV is 40-150 days (average, approximately 12 weeks). As with acute HAV infection, the clinical illness associated with acute HBV infection may range from mild disease to a disease as severe as FHF (< 1% of patients). After acute hepatitis resolves, 95% of adult patients and 5-10% of infected infants ultimately develop antibodies against hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)—that is, anti-HBs—clear HBsAg (and HBV virions), and fully recover. About 5% of adult patients and 90-95% of infected infants develop chronic infection.

Some patients, particularly individuals who are infected as neonates or as young children, have elevated serum levels of HBV DNA and a positive blood test for the presence of HBeAg but have normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and show minimal histologic evidence of liver damage. These individuals are in the so-called immune-tolerant phase of disease.[3, 4]

Years later, some but not all of these individuals may enter the so-called immune-active phase of disease. The HBV DNA may remain elevated as the liver experiences active inflammation and fibrosis. An elevated ALT level is noted during this period. Typically, the immune-active phase ends with loss of HBeAg and the development of antibodies to HBeAg (anti-HBe).[3, 4]

Individuals who seroconvert from an HBeAg-positive state to an HBeAg-negative state may enter the so-called inactive carrier state (previously known as the healthy carrier state). Such individuals are asymptomatic, have normal liver chemistry test results, and have normal or minimally abnormal liver biopsy results. Blood test evidence of HBV replication should be nonexistent or minimal, with a serum HBV DNA level in the range of 0-2000 IU/mL.[3, 5]

Inactive carriers remain infectious to others through parenteral or sexual transmission. Inactive carriers may ultimately develop anti-HBs and clear the virus. However, some inactive carriers develop chronic hepatitis, as determined by liver chemistry results, liver biopsy findings, and HBV DNA levels. Inactive carriers remain at risk for HCC, though the risk is low. At this point, no effective antiviral therapies are available for patients in an inactive carrier state.

Other patients who seroconvert may enter the so-called reactivation phase of disease. These individuals remain HBeAg-negative but have serum HBV DNA levels higher than 2000 IU/mL and show evidence of active liver inflammation. These patients are said to have HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis.[3]

Chronic

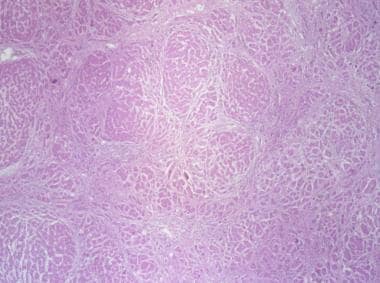

The 10-30% of HBsAg carriers who develop chronic hepatitis are often symptomatic. Fatigue is the most common symptom of chronic HBV infection. Acute disease flares occasionally occur, with symptoms and signs similar to those of acute hepatitis. Extrahepatic manifestations of the disease (eg, polyarteritis nodosa, cryoglobulinemia, andglomerulonephritis) may develop. Chronic hepatitis B patients have abnormal liver chemistry results, blood test evidence of active HBV replication, and inflammatory or fibrotic activity (see the images below) on liver biopsy.

Liver biopsy with hematoxylin stain showing stage 4 fibrosis (ie, cirrhosis) in patient with hepatitis B.

Liver biopsy with hematoxylin stain showing stage 4 fibrosis (ie, cirrhosis) in patient with hepatitis B.

Patients with chronic hepatitis may be considered either HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative. In North America and Northern Europe, about 80% of chronic hepatitis B cases are HBeAg positive and 20% HBeAg negative. In Mediterranean countries and in some parts of Asia, 30-50% of cases are HBeAg positive and 50-80% HBeAg negative.

Patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis have signs of active viral replication, with an HBV DNA level greater than 2 × 104 IU/mL.[3, 5]HBV DNA levels may be as high as 1011 IU/mL.

Patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis were presumably infected with wild-type virus at some point. Over time, they acquired a mutation in either the precore or the core promoter region of the viral genome. In such patients with a precore mutant state, HBV continues to replicate, but HBeAg is not produced. Patients with a core mutant state appear to have downregulated HBeAg production.[6]

The vast majority of patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B have a serum HBV DNA level greater than 2000 IU/mL. Typically, HBeAg-negative patients have lower HBV DNA levels than HBeAg-positive patients do. Commonly, the HBV DNA level is no higher than 2 × 104 IU/mL.[3, 5]

HBV and HCC

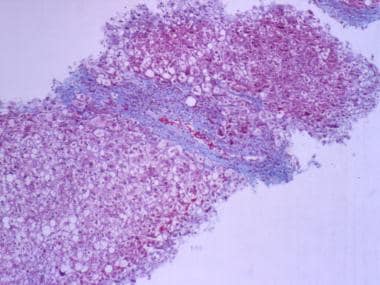

Ultimately, approximately 20% of HBsAg carriers (approximately 1% of all adult patients with acute HBV infection) go on to develop cirrhosis or HCC (see the image below). The incidence of HCC parallels the incidence of HBV infection in various countries around the world. Worldwide, up to 1 million cases of HCC are diagnosed each year. Most appear to be related to HBV infection.

Hepatic carcinoma, primary. Large multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma in 80-year-old man without cirrhosis.

Hepatic carcinoma, primary. Large multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma in 80-year-old man without cirrhosis.

In HBV-induced cirrhosis, as in cirrhosis due to other causes, hepatic inflammation and regeneration appear to stimulate mutational events and carcinogenesis. However, in HBV infection, in contrast to other liver diseases, the presence of cirrhosis is not a prerequisite for the development of HCC. The integration of HBV into the hepatocyte genome may lead to the activation of oncogenes or the inhibition of tumor suppressor genes. As an example, mutations or deletions of the p53 and RB tumor suppressor genes are seen in many cases of HCC.[7]

Multiple studies have demonstrated an association between elevated serum HBV DNA levels and an increased risk for the development of HCC.[8] Conversely, successful suppression of HBV infection by antiviral therapy can decrease the risk of developing HCC.[9, 10]

HCC is a treatable and potentially curable disease, whether the treatment entails tumor ablation (eg, with percutaneous injection of ethanol into the tumor), liver resection, or liver transplantation. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends screening for HBV-infected individuals who are at high risk for HCC, including men older than 45 years, persons with HBV-induced cirrhosis, and persons with a family history of HCC.

For these patients, ultrasonography of the liver and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) testing every 6 months are recommended. No specific recommendations have been made for patients at low risk for HCC. Some recommend that low-risk patients (including inactive carriers) undergo only AFP and liver chemistry testing every 6 months. The author’s practice is to screen all chronic hepatitis B patients with ultrasonography and AFP testing every 6 months, with inactive carriers undergoing liver chemistry and AFP testing every 6 months; however, this is controversial.

Hepatitis C

HCV has a viral incubation period of approximately 8 weeks. Most cases of acute HCV infection are asymptomatic. Even when it is symptomatic, acute HCV infection tends to follow a mild course, with aminotransferase levels rarely higher than 1000 U/L. Whether acute HCV infection is a cause of FHF remains controversial.

Approximately 15-30% of patients acutely infected with HCV lose virologic markers for HCV. Thus, approximately 70-85% of newly infected patients remain viremic and may develop chronic liver disease. In chronic hepatitis, patients may or may not be symptomatic, with fatigue being the predominant reported symptom. Aminotransferase levels may range from reference values (< 40 U/L) to values as high as 300 U/L. However, no clear-cut association exists between aminotransferase levels and symptoms or risk of disease progression.

An estimated 20% of patients with chronic hepatitis C experience progression to cirrhosis. This process may take 10-40 years. All patients who are newly diagnosed with well-compensated cirrhosis must be counseled regarding their risk of developing symptoms of liver failure (ie, decompensated cirrhosis). Only 30% of patients with well-compensated cirrhosis are anticipated to decompensate over a 10-year follow-up period.

Patients with HCV-induced cirrhosis are also at increased risk for the development of HCC (see the image below), especially in the setting of HBV coinfection. In the United States, HCC arises in 3-5% of patients with HCV-induced cirrhosis each year. Accordingly, routine screening (eg, ultrasonography and AFP testing every 6 months) is recommended in patients with HCV-induced cirrhosis to rule out the development of HCC. End-stage liver disease caused by HCV leads to about 10,000 deaths in the US each year.

Triple-phase CT scan of liver cancer, revealing classic findings of enhancement during arterial phase and delayed hypointensity during portal venous phase.

Triple-phase CT scan of liver cancer, revealing classic findings of enhancement during arterial phase and delayed hypointensity during portal venous phase.Hepatitis D

Simultaneous introduction of HBV and HDV into a patient results in the same clinical picture as acute infection with HBV alone. The resulting acute hepatitis may be mild or severe. Similarly, the risk of developing chronic HBV and HDV infection after acute exposure to both viruses is the same as the rate of developing chronic HBV infection after acute exposure to HBV (approximately 5% in adults). However, chronic HBV and HDV disease tends to progress more rapidly to cirrhosis than chronic HBV infection alone does.

Introduction of HDV into an individual already infected with HBV may have dramatic consequences. Superinfection may give HBsAg-positive patients the appearance of a sudden worsening or flare of hepatitis B. HDV superinfection may result in FHF.

Hepatitis E

HEV has an incubation period of 2-9 weeks. Acute HEV infection is generally less severe than acute HBV infection and is characterized by fluctuating aminotransferase levels. However, pregnant women, especially when infected during the third trimester, have a greater than 25% risk of mortality associated with acute HEV infection.[11] In a number of cases, FHF caused by HEV has necessitated liver transplantation.

Traditionally, HEV was not believed to cause chronic liver disease. However, several reports have described chronic hepatitis due to HEV in organ transplant recipients.[12] Liver histology revealed dense lymphocytic portal infiltrates with interface hepatitis, similar to the findings seen with hepatitis C infection. Some cases have progressed to cirrhosis.[13, 14]

Etiology

HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV (which requires coexisting HBV infection), and HEV cause the majority of clinical cases of viral hepatitis. Whether hepatitis G virus (HGV) is pathogenic in humans remains unclear. HAV, HBV, HCV, and HDV are the only hepatitis viruses endemic to the United States, HAV, HBV, and HCV are responsible for more than 90% of US cases of acute viral hepatitis. Whereas HAV is the most common cause of acute hepatitis in the United States, HCV is the most common cause of chronic hepatitis.

The following are typical patterns by which hepatitis viruses are transmitted, with + symbols indicating the frequency of transmission (ie, more + symbols indicate increased frequency).

Fecal-oral transmission frequency is as follows:

- HAV (+++)

- HEV (+++)

Parenteral transmission frequency is as follows:

- HBV (+++)

- HCV (+++)

- HDV (++)

- HGV (++)

- HAV (+)

Sexual transmission frequency is as follows:

- HBV (+++)

- HDV (++)

- HCV (+)

Perinatal transmission frequency is as follows:

- HBV (+++)

- HCV (+)

- HDV (+)

Sporadic (unknown) transmission frequency is as follows:

- HBV (+)

- HCV (+)

Hepatitis A

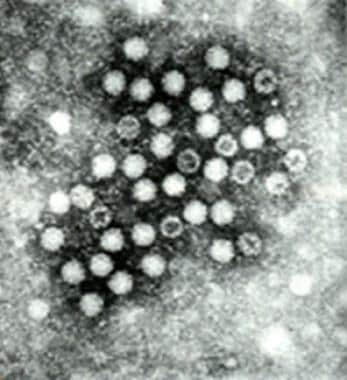

HAV (see the image below), a member of the Picornaviridae family, is an RNA virus with a size of 7.5 kb and a diameter of 27 nm. It has 1 serotype but multiple genotypes. Classic findings of acute HAV infection include a mononuclear cell infiltrate, interface hepatitis, focal hepatocyte dropout, ballooning degeneration, and acidophilic (Councilman-like) bodies. HAV is present in the highest concentration in the feces of infected individuals; the greatest fecal viral load tends to occur near the end of the HAV incubation period.

Most commonly, the virus spreads from person to person via the fecal-oral route. Contaminated water and food, including shellfish collected from sewage-contaminated water, have also resulted in epidemics of HAV infection. The virus may also be spread through sexual (anal-oral) contact.[15] Transmission by blood transfusion is rare. Maternal-neonatal transmission has not been established.

Although HAV infection occurs throughout the world, the risk is highest in developing countries, areas of low socioeconomic status, and areas without sufficient sanitation. Higher infection rates also exist in settings where fecal-oral spread is likely, such as daycare centers.[1]

Other groups at high risk for HAV infection include international travelers, users of injection and noninjection drugs, and men who have sex with men.[1, 15] International travel was the most frequently identified risk factor reported by case patients in the United States in 2006. Close contacts of infected individuals are also at risk.[1] The secondary infection rate for hepatitis A virus in household contacts of patients with acute HAV infection is around 20%. Thus, secondary infection plays a significant role in the maintenance of HAV outbreaks.

Hepatitis B

HBV, a member of the Hepadnaviridae family, is a 3.2-kb partially doubled-stranded DNA virus. The positive strand is incomplete. The complete negative strand has 4 overlapping genes, as follows:

- Gene S codes for HBsAg, a viral surface polypeptide

- Gene C codes for HBcAg, the nucleocapsid protein; it also codes for HBeAg, whose function is unknown

- Gene P codes for a DNA polymerase that has reverse transcriptase activity

- Gene X codes for the X protein that has transcription-regulating activity

The viral core particle consists of a nucleocapsid, HBcAg, which surrounds HBV DNA, and DNA polymerase. The nucleocapsid is coated with HBsAg. The intact HBV virion is known as the Dane particle. Dane particles and spheres and tubules containing only HBsAg are found in the blood of infected patients. In contrast, HBcAg is not detected in the circulation. It can be identified by immunohistochemical staining of infected liver tissue.

HBV is known to have 8 genotypic variants (genotypes A-H). Although preliminary studies suggest that particular HBV genotypes may predict the virus’s response to therapy or may be associated with more aggressive disease, it would be premature to incorporate HBV genotype testing into clinical practice on a routine basis.

HBV is readily detected in serum and is seen at very low levels in semen, vaginal mucus, saliva, and tears. The virus is not detected in urine, stool, or sweat. HBV can survive storage at –20°C (–4°F) and heating at 60°C (140°F) for 4 hours. It is inactivated by heating at 100°C (212°F) for 10 min or by washing with sodium hypochlorite (bleach).

The major reservoir of HBV in the United States consists of the 1.25 million people with chronic HBV infection.[1] In this group, those with HBeAg in their serum tend to have higher viral titers and thus greater infectivity.

HBV is transmitted both parenterally and sexually, most often by mucous membrane exposure or percutaneous exposure to infectious body fluids. Saliva, serum, and semen all have been determined to be infectious. Percutaneous exposures leading to the transmission of HBV include transfusion of blood or blood products, injection drug use with shared needles, hemodialysis, and needlesticks (or other wounds caused by sharp implements) in health care workers.

Globally and in the United States, perinatal transmission is one of the major modes of transmission. The greatest risk of perinatal transmission occurs in infants of HBeAg-positive women. By age 6 months, these children have a 70-90% risk of infection, and of those who become infection, about 90% will go on to develop chronic infection with HBV.

For infants born to HBeAg-negative women, the risk of infection is approximately 10-40%, with a chronic infection rate of 40-70%. Even if transmission does not occur in the perinatal period, these children are still at significant risk for the development of infection during early childhood.

Groups at high risk for HBV infection include intravenous (IV) drug users, persons born in endemic areas, and men who have sex with men.[2] Others at risk include health care workers exposed to infected blood or bodily fluids, recipients of multiple blood transfusions, patients undergoing hemodialysis, heterosexual persons with multiple partners or a history of sexually transmitted disease, institutionalized persons (eg, prisoners), developmentally disabled persons, and household contacts or sexual partners of HBV carriers.[2]

Hepatitis C

HCV, a member of the Flaviviridae family, is a 9.4-kb RNA virus with a diameter of 55 nm. It has 1 serotype, but at least 6 major genotypes and more than 80 subtypes are described, with as little as 55% genetic sequence homology. Genotype 1b is the genotype most commonly seen in the United States, Europe, Japan, and Taiwan. Genotypes 1b and 1a (also common in the US) are less responsive to interferon therapy than other HCV genotypes are. The wide genetic variability of HCV hampers the efforts of scientists to design an effective anti-HCV vaccine.

HCV can be transmitted parenterally, perinatally, and sexually. Transmission occurs by percutaneous exposure to infected blood and plasma.[16] The virus is transmitted most reliably through transfusion of infected blood or blood products, transplantation of organs from infected donors, and sharing of contaminated needles among IV drug users.[16]Transmission by sexual activity and household contact occurs less frequently. Perinatal transmission occurs but is uncommon.

Genetic variations and HCV clearance

Genetic polymorphisms involving the IL28Bgene have been found to affect the odds that HCV can be cleared in a given patient. TheIL28B gene encodes interferon (IFN) lambda-3. A single nucleotide polymorphism 3 kb upstream of the IL28B gene was associated with patients’ ability to clear HCV spontaneously.

Fifty-three percent of patients with the favorable C/C genotype spontaneously cleared the virus. Only 23% of patients with the less favorable T/T genotype spontaneously cleared the virus.[17] Of the patients who were chronically infected with HCV, those with the C/C genotype were more likely to see viral eradication after treatment with pegylated IFN (Peg-IFN) plus ribavirin.[18]

The C/C genotype was more common in persons of European ancestry than in those of African ancestry. In contrast, the T/T genotype was more common in persons of African ancestry.[17] These observations may help to explain why black individuals typically exhibit lower sustained virologic response (SVR) rates than white persons when treated with Peg-IFN plus ribavirin.

Hepatitis D

HDV, the single species in the Deltavirus genus, is a 1.7-kb single-stranded RNA virus. The viral particle is 36 nm in diameter and contains hepatitis D antigen (HDAg) and the RNA strand. It uses HBsAg as its envelope protein; thus, HBV coinfection is necessary for the packaging and release of HDV virions from infected hepatocytes.

Modes of transmission for HDV are similar to those for HBV. HDV is transmitted by exposure to infected blood and blood products. It can be transmitted percutaneously and sexually.[19]Perinatal transmission is rare.

Hepatitis E

HEV, the single species in the Hepevirus genus, is a 7.5-kb single-stranded RNA virus that is 32-34 nm in diameter. It is transmitted primarily via the fecal-oral route, with fecally contaminated water providing the most common means of transmission.[20, 21] Person-to-person transmission is rare, though maternal-neonatal transmission does occur.[21]Zoonotic spread is possible because some nonhuman primates (cows, pigs, sheep, goats, and rodents) are susceptible to the disease.[20]

Other viruses

Hepatitis G virus (HGV) is similar to viruses in the Flaviviridae family, which includes HCV. The HGV genome codes for 2900 amino acids. The virus has 95% homology (at the amino acid level) with hepatitis GB virus C (HGBV-C) and 26% homology (at the amino acid level) with HCV. It can be transmitted through blood and blood products.[21] HGV coinfection is observed in 6% of chronic HBV infections and in 10% of chronic HCV infections. HGV is associated with acute and chronic liver disease, but it has not been clearly implicated as an etiologic agent of hepatitis.

Other known viruses (eg, CMV, EBV, HSV, and varicella-zoster virus [VZV]) may also cause inflammation of the liver, but they do not primarily target the liver.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts national surveillance for acute hepatitis A, B, and C. In 2007, 2979 cases of acute symptomatic HAV infection were reported. This was the lowest incidence of HAV infection recorded to that point and represented a 90% decline from annual cases reported from 1995 through 2005. Because a good deal of HAV infections may be asymptomatic or may go unreported, the CDC estimated that the actual number of new HAV infections in 2007 was about 25,000.[1]

For HBV infection, 4519 acute, symptomatic cases were reported in 2007—also the lowest rate recorded to that point. With correction for asymptomatic cases and underreporting, the true number was estimated to be 43,000 new infections in 2007.[1] The incidence of childhood HBV infection is not well established, because more than 90% of such infections in children are asymptomatic.

Rates of HBV infection were highest in non-Hispanic blacks in 2007 (2.3 cases per 100,000).[1] Chronic HBV infection has a higher prevalence among Asian Pacific Islanders and non-Hispanic blacks.

The number of confirmed cases of acute hepatitis C increased slightly for 2007, from 802 reported cases in 2006 to 849 in 2007. The actual number of new HCV infections in 2007 was estimated to be around 17,000.[1] About 70-90% of people infected progress to chronic HCV infection.[16] Approximately 3.2 million people In the United States have chronic hepatitis C.

International statistics

Worldwide, HAV is responsible for an estimated 1.4 million infections annually.[15] HBV causes more than 4 million cases of acute hepatitis per year throughout the world, and it is estimated that approximately 350 million people are chronically infected with the virus.[2] HBV leads to 1 million deaths annually as a result of viral hepatitis–induced liver disease.[2]

The worldwide annual incidence of acute HCV infection is not easily estimated, because patients are often asymptomatic. An estimated 170 million people are chronically infected with HCV worldwide.[16] China, the US, and Russia have the largest populations of anti-HCV positive IV drug users (IDUs). It is estimated that 6.4 million IDUs worldwide are positive for antibody to HBcAg (anti-HBc), and 1.2 million are HBsAg-positive.[22]

Hepatitis A virus

HAV is transmitted commonly most via the fecal-oral route. Cases of transfusion-associated HAV or illness caused by inoculation are uncommon.

HAV infection is common in the less-developed nations of Africa, Asia, and Central and South America; the Middle East has a particularly high prevalence. Most patients in these regions are infected when they are young children. Uninfected adult travelers who visit these regions are at risk for infection.

Epidemics of HAV infection may be explained by person-to-person contact, such as occurs at institutions, or by exposure to a common source, such as consumption of contaminated water or food.

As sanitation has improved, the overall prevalence of hepatitis A in the United States and in other parts of the developed world has decreased to less than 50% of the population. Because fewer individuals enter adulthood with previous exposure to HAV, adults in the United States are actually at greater risk for developing significant HAV infection today than they were a generation ago.

Hepatitis B virus

Infection with HBV is defined by the presence of HBsAg. Approximately 90-95% of neonates with acute HBV infection and 5% of adults with acute infection develop chronic HBV infection. In the remaining patients, the infection clears, and these patients develop a lifelong immunity against repeated infections.

Out of the approximately 5% of the world’s population (ie, 350 million people) that is chronically infected with HBV, about 20% will eventually develop HBV-related cirrhosis orHCC. According to the World Health Organization, HBV is the 10th leading cause of death worldwide.[23]

More than 10% of people living in sub-Saharan Africa and in East Asia are infected with HBV. Maintenance of a high HBsAg carriage rate in these parts of the world is partially explained by the high prevalence of perinatal transmission and by the low rate of HBV clearance by neonates.

In the United States, about 250-350 patients die of HBV-associated FHF each year. A pool of approximately 1.25 million chronic HBV carriers exists in the United States. Of these patients, 4000 die of HBV-induced cirrhosis each year, and 1000 die of HBV-induced HCC.

Perinatal transmission

The vast majority of HBV cases around the world result from perinatal transmission. Infection appears to occur during the intrapartum period, or, rarely, in utero. Neonates infected via perinatal infection are usually asymptomatic. Although breast milk can contain HBV virions, the role of breastfeeding in transmission is unclear.

Sexual transmission

HBV is transmitted more easily than human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or HCV. Infection is associated with vaginal intercourse, genital-rectal intercourse, and oral-genital intercourse. An estimated 30% of sexual partners of patients infected with HBV also contract HBV infection. However, HBV cannot be transmitted through kissing, hugging, or household contact (eg, sharing towels, eating utensils, or food). Sexual activity is estimated to account for as many as 50% of HBV cases in the US.

Parenteral transmission

HBV was once a common cause of posttransfusion hepatitis. Screening of US blood donors for anti-HBc, beginning in the early 1970s, dramatically reduced the rate of HBV infection associated with blood transfusion. Currently, approximately 1 HBV transmission occurs per 250,000 individuals transfused.

Patients with hemophilia, those on renal dialysis, and those who have undergone organ transplantation remain at increased risk of HBV infection. IV drug use accounts for 20% of US cases of HBV. A history of HBV exposure is identified in approximately 50% of IDUs. The risk of acquiring HBV after a needle stick from an infected patient is estimated to be as high as 5%.

Sporadic cases

In approximately 27% of cases, the cause of HBV infection is unknown. Some of these cases, in fact, may be due to sexual transmission or contact with blood.

Hepatitis C virus

HCV is the most frequent cause of parenteral non-A, non-B (NANB) hepatitis worldwide. Hepatitis C is prevalent in 0.5-2% of populations in nations around the world. The highest rates of disease prevalence are found in patients with hemophilia and in IDUs.

In the 1980s, as many as 180,000 new cases of HCV infection were described each year in the United States; by 1995, there were only 28,000 new cases each year.[24] The decreasing incidence of HCV was explained by a decline in the number of cases of transfusion-associated hepatitis (because of improved screening of blood products) and by a decline in the number of cases associated with IV drug use.

Transmission via blood transfusion

Screening of the US blood supply has dramatically reduced the incidence of transfusion-associated HCV infection.[16, 25]Before 1990, 37-58% of cases of acute HCV infection (then known as NANB) were attributed to the transfusion of contaminated blood products; today, only about 4% of acute cases are attributed to transfusion. HCV is estimated to contaminate 0.01-0.001% of units of transfused blood. Acute hepatitis C remains an important issue in dialysis units, where patients’ risk for HCV infection is about 0.15% per year.

Transmission via intravenous and intranasal drug use

IV drug use remains an important mode of transmitting HCV. The use of IV drugs and the sharing of paraphernalia used in the intranasal snorting of cocaine and heroin account for approximately 60% of new cases of HCV infection. More than 90% of patients with a history of IV drug use have been exposed to HCV.

Transmission via occupational exposure

Occupational exposure to HCV accounts for approximately 4% of new infections. On average, the chance of acquiring HCV after a needle-stick injury involving an infected patient is 1.8% (range, 0-7%). Reports of HCV transmission from healthcare workers to patients are extremely uncommon.

Sexual transmission

Approximately 20% of cases of hepatitis C appear to be due to sexual contact. In contrast to hepatitis B, approximately 5% of the sexual partners of those infected with HCV contract hepatitis C.

The US Public Health Service (USPHS) recommends that persons infected with HCV be informed of the potential for sexual transmission. Sexual partners should be tested for the presence of antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV). Safe-sex precautions are recommended for patients with multiple sex partners. Current guidelines do not recommend the use of barrier precautions for patients with a steady sexual partner. However, patients should avoid sharing razors and toothbrushes with others. In addition, contact with patients’ blood should be avoided.

Perinatal transmission

Perinatal transmission of HCV appears to be uncommon. It is observed in fewer than 5% of children born to mothers infected with HCV. The risk of perinatal transmission of HCV is higher (about 18%) in children born to mothers coinfected with HIV and HCV.[26] Available data show no increase in HCV infection in babies who are breastfed. The USPHS does not advise against pregnancy or breastfeeding for women infected with HCV.

Hepatitis D virus

HDV requires the presence of HBV to replicate; thus, HDV infection develops only in patients who are positive for HBsAg.[27] Patients may acquire HDV as a coinfection (at the same time that they contract HBV), or the HDV may superinfect patients who are chronic HBV carriers. Although hepatitis D is not a reportable disease, the CDC estimates that it results in 7500 infections each year. Approximately 4% of cases of acute hepatitis B are thought to involve coinfection with HDV.

HDV is believed to infect approximately 5% of the world’s 350 million HBsAg carriers. The prevalence of HDV infection in South America and Africa is high. Italy and Greece are areas of intermediate endemicity and are well studied. Only about 1% of HBV-infected individuals in the United States and Northern Europe are coinfected with HDV.

The sharing of contaminated needles in IV drug use is thought to be the most common means of transmitting HDV. IDUs who are also positive for HBsAg have been found to have HDV prevalence rates ranging from 17% to 90%. Sexual transmission and perinatal transmission are also described. The prevalence of HDV in prostitutes in Greece and Taiwan is high.

Hepatitis E virus

HEV is the primary cause of enterally transmitted NANB hepatitis. It is transmitted via the fecal-oral route and appears to be endemic in some parts of the less-developed countries, where most outbreaks occur. HEV can also be transmitted vertically to the babies of HEV-infected mothers. It is associated with a high neonatal mortality.[28]

In one report, anti-HEV antibodies were found to be present in 29% of urban children and 24% of rural children in northern India.[29] Sporadic infections are observed in persons traveling from Western countries to these regions.

Prognosis

The prognosis of viral hepatitis varies, depending on the causative virus.

HAV infection usually is mild and self-limited. Overall mortality is approximately 0.01%; children younger than 5 years and adults older than 50 years have the highest case-fatality rates. Infection confers lifelong immunity against the virus. Older patients are at greater risk for severe disease. Whereas icteric disease occurs in fewer than 10% of children younger than 6 years, it occurs in 40-50% of older children and in 70-80% of adults with HAV. Three rare complications are relapsing hepatitis, cholestatic hepatitis, and FHF.

The risk of chronic HBV infection in infected older children and adults approaches 5-10%. Patients with such infection are at risk for cirrhosis and HCC. FHF develops in 0.5-1% of patients infected with HBV; the case-fatality rate in these patients is 80%. Chronic HBV infection is responsible for approximately 5000 deaths per year from chronic liver disease in the United States.

Chronic infection develops in 50-60% of patients with hepatitis C. Chronically infected patients are at risk for chronic active hepatitis, cirrhosis, and HCC. In the United States, chronic HCV infection is the leading indication for liver transplantation, and an estimated 8,000-10,000 chronic liver disease deaths occur as a result of HCV infection each year.[1]

Patients with chronic HBV infection who are coinfected with HDV also tend to develop chronic HDV infection. Chronic coinfection with HBV and HDV often leads to rapidly progressive subacute or chronic hepatitis, with as many as 70-80% of these patients eventually developing cirrhosis.

HEV infection usually is mild and self-limited. The case-fatality rate reaches 15-20% in pregnant women. HEV infection does not result in chronic disease.

Refer patients with infectious hepatitis to their primary care providers for further counseling specific to their disease; the specific etiologic virus is unlikely to be known at the time of discharge from the emergency department.

Counsel patients regarding the importance of follow-up care to monitor for evidence of disease progression or development of complications. Remind them to exercise meticulous personal hygiene, including thorough hand washing. Instruct them not to share any articles with potential for contamination with blood, semen, or saliva, including needles, toothbrushes, or razors.

Inform food handlers suspected of having HAV that they should not return to work until their primary care physician can confirm that they are no longer shedding virus. Instruct patients to refrain from using any hepatotoxins, including ethanol and acetaminophen.

This is an advertisement. Click below for online shopping:

https://linksredirect.com/?pub_id=11719CL10653&url=http%3A//www.flipkart.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment