Astronomy - Swing Low, Sweet Sun: It’s Solstice Time

Daylight ebbs to a minimum on Wednesday's winter solstice, but not for long. The very next day, the Sun turns back north and the cycle of light begins again.

The Sun swings low across the southern sky at the start of winter, casting long shadows and abbreviating daylight. On the plus side, ice halos, and sundogs are more common in winter.

Bob King

Bob King

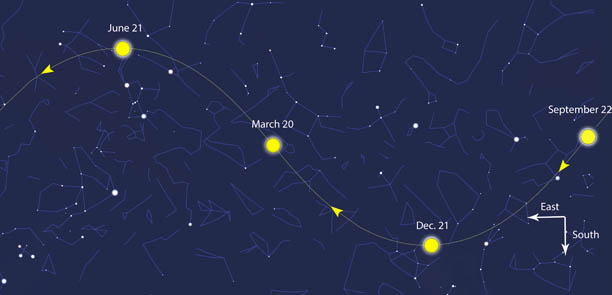

"Limbo lower now. Limbo lower now. How low can you go?" The Sun's been doing the limbo since last June, when it stood highest in the sky on the first day of summer. The following day, it began slipping southward along its yearly circle 'round the sky called the ecliptic. And on Wednesday morning, December 21st, at 5:44 a.m. Eastern time (10:44 UT), it limbos lowest, reaching the nadir of its arc.

How low is low? Depends on your latitude. At the north pole, the Sun dropped below the horizon after the first day of fall, not to return until next spring. The pole experienced the last vestige of twilight in mid-November and won't sense the Sun's presence again until about January 28th, when twilight returns.

In Anchorage, Alaska, the Sun tops at 5.5° altitude at local noon on the solstice — that's just three fingers held together at arm's length above the horizon. Daylight lovers there face a severe deficit with just 5 hours 28 minutes separating sunrise from sunset.

We complain here in Duluth, Minnesota, about driving around in a "tunnel of darkness" for much of the winter, but have it easy in comparison, with a more "tropical" 8 hours 32 minutes of sunshine and a 20° high Sun. It gets better as you travel south: in Duluth, Georgia (latitude 34°), the Sun stands more than three fists high (33°) high and days are longer yet.

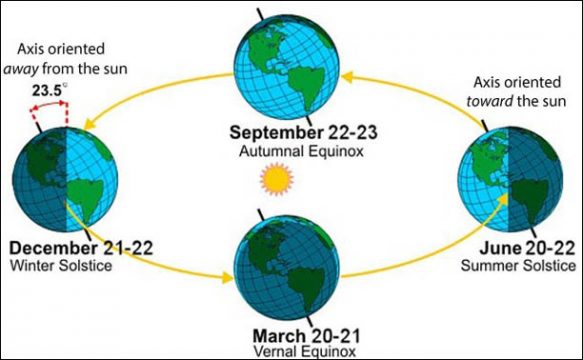

During Earth’s yearly revolution, the Northern Hemisphere tilts away from the Sun at the winter solstice (left). The Sun cuts a low path across the sky and days are short. At the same time, the Southern Hemisphere tilts away from the Sun at the start of its summer season. The seasons are caused by the tilt of the Earth’s axis and its changing orientation to the Sun during its yearly orbit.

NOAA / NWS

NOAA / NWS

But no matter where you live in the Northern Hemisphere, the winter solstice marks the Sun's lowest point in the sky and shortest day of the year. Conversely, in the southern hemisphere, the Sun reaches the highest point of its arc — summer solstice — and the nights are shortest.

Solstices have always had something of a split personality, bright side and dark side, as it were. Dearth of daylight defines the dark side, but we all know that when you've reached bottom, the only way to go is up. That's exactly what happens the moment after the Sun passes through its low point. It begins moving northward up the ecliptic and back toward summer.

Rockin' the Light

Orion the Hunter rises over Lake Superior as participants in a winter solstice gathering in Two Harbors, Minnesota, warm themselves by the fire.

Bob King

Bob King

Our ancient ancestors, who liked a good party as much as we do, celebrated the return of the light at this darkest time of the year with big holiday bashes like Dies Natalis Solis Invicti or "birthday of the unconquered Sun" (Rome), Saturnalia(Rome), the Yule (Norway), and other pre-Christian festivities. The December 25th date for Christmas, the time of celebrating the birth of Jesus, may have been chosen to tap into the spirit of these earlier celebrations, but with a more sacred take.

Calendars for the same year sometimes show different dates for the solstice, typically December 21st or 22nd, because of time zone differences. For instance, if the solstice occurs at 2 a.m. in London, England on December 22nd, it happens in Boston at 9 p.m. on December 21st.

While December 21st and 22nd are the most common dates, the solstice can also occur as early as December 20th and as late as December 23rd. The spread in dates has to do with our calendar system, which measures time uniformly across the year, versus the slippery clock that is the real Earth. The time it takes for the Sun to return to the solstice and equinox points varies year to year according to the orbital and daily rotational motion of the Earth, which are acted upon by the Sun, Moon and planets. Even precession, the wobble of Earth's axis caused by the tug of the Moon and Sun, contributes to the shifting date of the winter solstice from the norm of December 21–22 to its extremes.

Solstice is really a two-part word forged from the Latin "sol" (sun) and "sistere" (to stand still). That's not a bad description of what really happens. The Sun, which has been racing south along the ecliptic since late summer, appears to slow down and practically stand still around the time of solstice as it travels along the bottom of its descending arc. Changes in sunrise and sunset times almost come to a halt as if the Sun were stuck in place.

Sticky Sunsets

Counter to intuition, the Sun sets earliest before the winter solstice (and rises latest after the solstice), not on the date itself. Once again, it’s because our clocks keep steady, uniform time compared to the more “elastic” timekeeping system the Sun follows.

A man-made clock will always measure the interval from one noon to the next as exactly 24 hours, but the solar clock can vary by a fraction of a second up to a half minute from one noon to the next due to the tilt of Earth’s axis and the planet’s changing orbital speed.

Earth’s rotation causes the Sun to rise in the east and set in the west, while Earth’s revolution around the Sun causes the sun to shift a short distance eastward each day. We sense the Sun’s eastward drift in the recent reappearance of Jupiter in the morning sky. Two months ago it rose in bright twilight; since then, the Sun has moved off to the east, leaving Jupiter hanging high in a dark sky before dawn.

Earth’s elliptical orbit causes its distance from the Sun and orbital speed to vary during a year. Near its January perihelion, the Sun appears to move more quickly across the sky (eastward), delaying December sunrises and causing sunsets to grow later early on in the month.

Bob King

Bob King

When Earth and Sun are closest in December and January, the Sun appears to move eastward a bit faster, covering more sky each day compared to the other seasons. This creates a delay in sunrise time, making for later sunrises. A later sunrise also means the Sun arrives at the sunset point later. Let's use this fact to explore the disconnect between the solstice and earliest sunsets.

In late November and early December, the Sun is sinking to its southernmost point in the sky, so its daytime arc is getting shorter and shorter, lower and lower. This southward slide pairs up with the Sun’s flight east, delaying sunrise even more.

Combine the 23.5° tilt of our planet's axis with its annual motion around the Sun, and the Sun appears to bob up and down from high to low (summer to winter) during the course of a year. Around the time of the winter solstice, the Sun appears to "stand still" for a time while reversing direction from south to north.

Diagram: Bob King; Source: Stellarium

Diagram: Bob King; Source: Stellarium

Through late November, the Sun's southward motion more than cancels out its eastward movement, causing it to keep setting earlier and earlier. But beginning around December 2nd, the Sun’s speedier eastern motion (due to Earth's increasing orbital speed) overpowers the tiny bit of southern travel remaining at the bottom of its curve, causing it to slow down, “stall,” and then start setting later. That’s why the earliest sunsets occur in early December and grow later by mid-month before the solstice.

At the solstice, the Sun begins moving north again. Its arc steepens and days begin to get longer. But that extra eastward movement still keeps it rising later for a time until the effect is canceled out by the Sun's steady and steepening northward creep up the ecliptic. Result? Sunrises start coming earlier. This happens in early January from the mid-northern latitudes, when the Sun begins to both set and rise later. To see how the cycle of the Sun’s rising and setting plays out for your city, click here and type in your location.

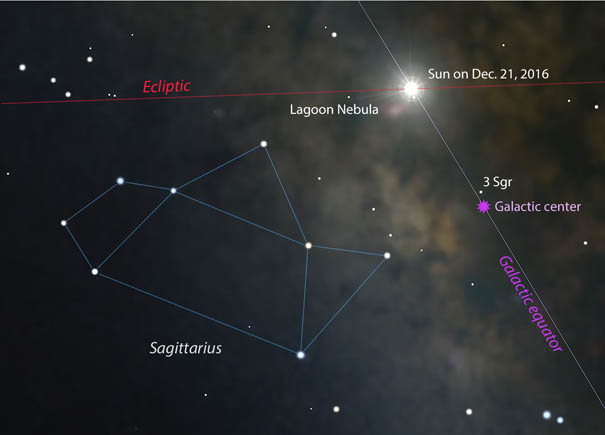

If we could jettison the atmosphere, we'd see that the Sun shines near the Lagoon Nebula in Sagittarius on the winter solstice. Around 11:30 a.m. on December 21st, it crosses the galactic equator –5.5° northeast of the center of the Milky Way.

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

Map: Bob King, Source: Stellarium

With later sunsets and earlier sunrises working in tandem, keen-eyed skywatchers easily sense the increase in daylight as early as mid-January.

Despite the cold and brief sunshine, solstice time does have distinct advantages. With 4:30 p.m. sunsets, skywatchers can get out early to enjoy the night and return to the blessed warmth of their homes by 8:00. Late sunrises also mean many of us can observe Jupiter and other sky sights before going to work in the morning.

For the properly-dressed amateur astronomer, an abundance of darkness is reason to cheer on this special day. Let me be the first to wish you a happy solstice!

No comments:

Post a Comment