Portuguese India

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

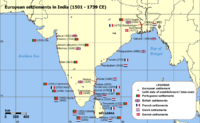

Portuguese India (Portuguese: Índia Portuguesa or Estado da Índia) refers to the aggregate of Portugal's colonial holdings inIndia. At the time of British India's independence in 1947, Portuguese India included a number of enclaves on India's western coast, including Goa proper, as well as the coastal enclaves of Daman (Port:Damão) and Diu, and the enclaves of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, which lie inland from Daman. The territories of Portuguese India have sometimes been referred to collectively as Goa.

Contents[hide] |

Portugal, desperate to reestablish trade with India afterIslam had cut off all traditional sea and land routes to India with the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, discovered a new sea route to India by way of the Horn of Africa. Originally purely a commercial venture, Portugal's mission quickly became baptizing India into Roman Catholicism. Lax with admission requirements, the Church installed anInquisition Board in 1561 that continued almost unbroken until 1812 in an effort to conform Indians to the teachings of theRoman Catholic Church. Portugal's control of colonies ended in 1960 with an armed attack by the Republic of India and the reincorporation of Goa into India.

Early history

The first Portuguese encounter with India occurred on May 20, 1498 when Vasco da Gama landed in Calicut (present-day Kozhikode). Over the objections of Arab merchants, da Gama secured an ambiguous letter of concession for trading rights from the Zamorin, Calicut's local ruler, but had to sail off without warning after the Zamorin insisted on his leaving behind all his goods as collateral. Da Gama kept his goods, but left behind a few Portuguese with orders to start a trading post.

In 1510, Portuguese admiral Afonso de Albuquerque defeated the Bijapur sultans on behalf of a local sovereign, Timayya, leading to the establishment of a permanent settlement in Velha Goa (or Old Goa). The Southern Province, also known simply as Goa, served as the headquarters of Portuguese India, and seat of the Portuguese viceroy who governed the Portuguese possessions in Asia.

The Portuguese acquired several territories from the Sultans of Gujarat: Daman (occupied 1531, formally ceded 1539); Salsette, Bombay, and Baçaim (occupied 1534); and Diu (ceded 1535). Those possessions became the Northern Province of Portuguese India, which extended almost 100 km along the coast from Daman to Chaul, and in places 30–50 km inland. The fortress-town of Baçaim ruled the province. Britain received Bombay (present day Mumbai) in 1661 as part of the Portuguese Princess Catherine of Braganza's dowry to Charles II of England. The Marathas claimed most of the Northern Province in 1739, and Portugal acquired Dadra and Nagar Haveli in 1779.

The Goa Inquisition

Overview

The Portuguese conducted a program to convert the native population (mainly Hindus) by torture, reportedly more extensive and endured for a longer period than the Spanish Inquisition. Thousands of citizens suffered horrors and execution, leading to large portions of Goa being depopulated [1][2]. Eventually, royal decree ended the Inquisition in Goa in 1812 a consequence of Napoleon's Iberian Peninsular campaign.

History

The Goa Inquisitionrefers to the office of the Inquisitionacting in the Indianstate of Goa and the rest of the Portuguese empire in Asia. Established in 1560, the committed had been briefly suppressed from 1774-1778, and finally abolished in 1812.

The Portuguese instituted the Inquisition to punish relapsed New Christians. They had been Jews and Muslims who had converted to Catholicism, as well as their descendants, suspected of practicing their former religions in secret. In Goa, the Inquisition also turned its attention to Indian converts from Hinduism or Islam thought to have returned to their original religion. In addition, the Inquisition prosecuted non-converts who broke prohibitions against the observance of Hindu or Muslim rites or interfered with Portuguese attempts to convert non-Christians to Catholicism.[3] While ostensibly to preserve the Catholic faith, the Inquisition in effect served as an instrument of social control, as well as a method of confiscating victims' property and enriching the Inquisitors, against Indian Catholics and Hindus. [4]

Most of the Goa Inquisition's records had been destroyed after its abolition in 1812, rendering knowledge of the exact number of the Inquisition's victims impossible. Based on the records that survived, H. P. Salomon and I. S. D. Sassoon state that between the Inquisition's beginning in 1561 and its temporary abolition in 1774, the Inquisition brought to trial 16,202 people. Of that number, 57 received death sentences and suffered execution; another 64 had been burned in effigy. Others received lesser punishments or penance, but the fate of many of the Inquisition's victims remains unknown.[5]

In Europe, the Goa Inquisition became notorious for its cruelty and use of torture, and the French philosopher Voltaire wrote: "Goa is sadly famous for its inquisition, which is contrary to humanity as much as to commerce. The Portuguese monks deluded us into believing that the Indian populace was worshiping The Devil, while it is they who served him."[6]

Background

In the fifteenth century, the Portuguese explored the sea route to India and Pope Nicholas V enacted the Papal bull Romanus Pontifex. This bull granted the patronage of the propagation of the Christian faith in Asia to the Portuguese and remunerate them with a trade monopoly for newly discovered areas[7].

After Vasco da Gama arrived in India in 1498, the trade became prosperous, but the Portuguese showed little interest in proselytization. After four decades in India, the Catholic Church embarked upon a program of spreading Christianity throughout Asia. Missionaries of the newly foundedSociety of Jesus traveled to Goa, receiving support from the Portuguese colonial government with incentives for baptized Christians. They offered rice donations for the poor, good positions in the Portuguese colonies for the middle class and military support for local rulers[8].

Many Indians converted opportunistically, receiving the name from the missionaries asRice Christians. The Jesuit missionaries doubted the sincerity of the conversion, suspecting that the converts practiced their former religions in private. Seen as a threat to the immaculateness of the Christian belief,Saint Francis Xavier, in a 1545 letter to John III of Portugal, requested an Inquisition set up for purification of the faith in Goa.

King Manuel I of Portugal had been persecuting Jews in Portugal since 1497. Jews had been forced to become New Christians, called Conversos or Marranos. They experienced harassment. Under king John III of Portugal, Jews became targets of the Inquisition. For that reason many New Christians emigrated to the colonies. Garcia de Orta emerged as one of the most famous New Christians. A professor, he emigrated in 1534, posthumously receiving found guilty of practicing Judaism[9].

Beginning

The first inquisitors, Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques, established themselves in the former raja of Goa's palace, forcing the Portuguese viceroy to relocate to a smaller residence. In their first act, the inquisitors forbade Hindus from publicly practice of their faith through fear of death. Sephardic Jews living in Goa, many of whom had fled the Iberian Peninsula to escape the Spanish Inquisition, also experienced persecution. The narrative of Da Fonseca describes the violence and brutality of the inquisition. The records speak of the allocation of hundreds of prison cells to accommodate the arrested who awaited trial. Seventy-one "autos da fe" had been recorded. In the first few years alone, over 4000 people had been arrested, with 121 people reported as burnt alive at the stake[10].

Persecution of Hindus

R.N. Sakshena writes "in the name of the religion of peace and love, the tribunal(s) practiced cruelties to the extent that every word of theirs was a sentence of death."[11].

Historical background

The Portuguese colonial administration enacted anti-Hindu laws with the expressed intent to "humiliate Hindus" and encourage conversions to Christianity. They passed laws banning Christians from employing Hindus, and making the public worship of Hinduism a punishable violation[12]. The viceroy issued an order that prohibited Hindu pandits and physicians from entering the capital city on horseback or palanquins, the violation of which entailed a fine. Successive violations resulted in imprisonment. The law forbade Christian palanquin-bearers from carrying Hindus as passengers and Christian agricultural laborers to work in the lands owned by Hindus. and Hindus forbidden to employ Christian laborers.[13] The Inquisition guaranteed "protection" to Hindus who converted to Christianity. Thus, they initiated a new wave of baptisms of Hindus intimidated by the threat of brutal torture[14]. indus could escape the Portuguese Inquisition court by migrating to other parts of the subcontinent, tempered somewhat the calamity of the inquisition[15].

Persecution of non-Catholic-Syrian Christians

In 1599 under Aleixo de Menezes, the Synod of Diamper converted the Syriac Saint Thomas Christians (of the Orthodox faith) to the Roman Catholic Church by alleging that they practiced Nestorian heresy. The synod enforced severe restrictions on their faith and the practice of using Syriac/Aramaic. TheKerala Christians of Malabar maintained independence from Rome. The persecution of the Syrian Christians of Malabar resulted, rendering them politically insignificant. The Metropolitanate status was discontinued by the blocking of bishops from the Middle East; there were allegations of assassination attempts against Archdeacon George, allegedly to subjugate the entire church under Rome. The common prayer book, as well as many other publications, had been burnt; priests professing independence from Rome suffered imprisonment. The Portuguese pulled down some altars to make way for altars conforming to Catholic criteria. Saint Thomas Christians, resentful over those acts, later swore the Coonan Cross Oath, severing relations with the Catholic Church. They swore that from that day, neither they nor their children would have any relations with the Church of Rome, thereby marking the first freedom movement against the western powers in India.

In addition, non-Portuguese Christian missionaries also suffered persecuted from the Inquisitors. When the local clergy became jealous of a French priest operating in Madras, they lured him to Goa, then had him arrested and sent to the inquisition. the Hindu King of Carnatica (Karnataka) saved him by interceding on his behalf, laying siege to St. Thome and successfully demanding the release of the priest.[16]

Though officially repressed in 1774, Queen Maria I reinstated it in 1778. The British swept away the last vestiges of the Goa Inquisition when they occupied the city in 1812.

After India's independence

After India's independence from the British in 1947, Portugal refused to accede to India's request to relinquish control of its Indian possessions. The decision given by the International Court of Justice at The Hague, regarding access to Dadra and Nagar Haveli, after Indian citizens invaded the territory, had been indecisive[17].

From 1954, the Portuguese brutally suppressed peaceful Satyagrahis campaigns by Indians from outside Goa aimed to force the Portuguese to leave Goa.[18] The Portuguese quelled many revolts by the use of force, eliminating or jailing leaders eliminated. As a result, India closed its consulate (which had operated in Panjim since 1947), imposing an economic embargo against the territories of Portuguese Goa. The Indian Government adopted a "wait and watch" attitude from 1955 to 1961 with numerous representations to the Portuguese Salazar regime and attempts to highlight the issue before the international community.[19]In December 1961, India militarily invaded Goa, Daman and Diu, where they overwhelmed Portuguese resistance.[20][21]Portuguese armed forces had been instructed to either defeat the invaders or die and, though a cease-fire had been decreed, an official truce has never signed. [22]The Portuguese army offered only meager resistance, lacking heavy weapons and fielding 3,300 soldiers in the face of a heavily armed Indian force of over 30,000 troops enjoying Air and Naval support.[23] [24]. India formally annexed the territories were December 19, 1961.

The Salazar regime in Portugal refused to recognize Indian sovereignty over Goa; Daman and Diu continued representation in Portugal's National Assembly until 1974. Following the Carnation Revolution that year, the new government in Lisbon restored diplomatic relations with India, recognizing Indian sovereignty over Goa, Daman and Diu. Due to the military takeover, and since the wishes of the people of Portuguese India had never been taken into consideration (as required by UN Resolution 1514 (XV) of 1960 on "the right to self-determination" [25]—see also UN Resolutions 1541 and 1542 [26]), the people continue to have the right to Portuguese citizenship. Since 2006, that has been restricted to those born during Portuguese rule.

Postage stamps and postal history

Early postal history of the colony has remained obscure, but regular mail has been recorded with Lisbon beginning in 1825. Portugal had a postal convention with Great Britain, most mail probably routing throughBombay and carried on British packets. Portuguese postmarks date to 1854.

The first postage stamps had been issued October 1, 1871 for local use. The design simply consisted of a denomination in the center, with an oval band containing the inscriptions "SERVIÇO POSTAL" and "INDIA POST." In 1877, Portugal included India in its standard "crown" issue and from 1886 on, the pattern of regular stamp issues followed that of the other colonies closely, the main exception being a series of surcharges in 1912 produced by perforating existing stamps vertically through the middle and overprinting a new value on each side.

The last regular issue occurred on June 25, 1960, the 500th anniversary of the death of Prince Henry the Navigator. Stamps of India had been used first December 29, 1961, although the government accepted the old stamps until January 5, 1962. Portugal continued to issue stamps for the lost colony but none went on sale in the colony's post offices, thus have never been valid stamps.

No comments:

Post a Comment