Astronomy - Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter: Ten Years Over Mars

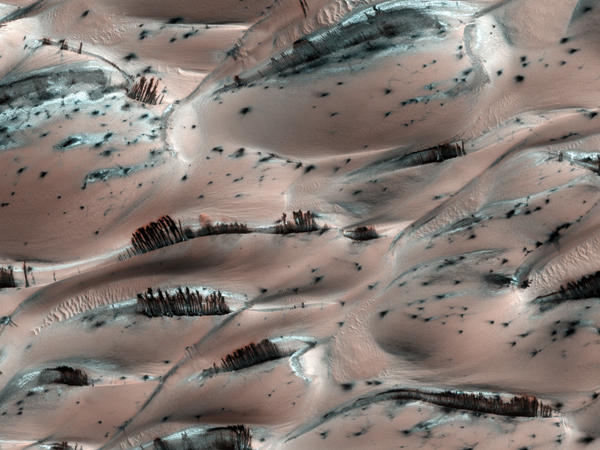

“Tree”-like tendrils of dark sand appear on Martian dunes due to the sublimation of carbon dioxide frost.

HIRISE / MRO / LPL (U. of Arizona) / NASA

HIRISE / MRO / LPL (U. of Arizona) / NASA

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) completed 10 years in orbit around Mars. That’s not bad for a spacecraft that had a primary mission lifetime of 2 years. Among its six main scientific instruments, all of which are still working, the standout has been HiRISE, the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment. This amazing telescopic camera can spot features as small as a picnic table.

Combined with imaging spectroscopy, which determines the make-up of surface materials, HiRISE has illustrated the stories of countless, highly varied Martian landscapes. And, crucially, its great longevity has allowed us to see many subtle — and a few dramatic — ways in which those landscapes change over time. Whole new aspects of Mars are revealed when we see the planet with this clarity and detail, and with the luxury of being able to pick the right targets on a planet that has become increasingly known to us.

We’ve seen incredible views of eroded canyons and meandering riverbeds, vast fields of curvaceous dunes, interlaced patterns of ice and rock looking almost biological in their filigreed complexity, and an endless menagerie of impact crater shapes and styles. From a sheer aesthetic perspective, these images continue to astound. They show us that whatever it is in nature that rouses us to wonder, triggers awe and appreciation of beauty, it is not limited to our home planet.

In the early 20th century, charismatic American astronomer Percival Lowell had the world briefly enthralled with his “observations” of canals carrying irrigation water for a thirsty civilization, until better images revealed them to be mirages. Ever since we’ve been following that water, chasing it underground and into the distant past. At the beginning of the Space Age, belief was widespread that vegetation caused the planet’s seasonal changes in color. But our first missions in the 1960s showed a lunar-like world: cratered, dead, and quiescent.

Those fly-bys provided only partial and misleading glimpses. In 1971 Mariner 9, our first orbiter, arrived to discover that, contrary to first impressions, Mars had seen lots of action. But it was a geologically dead world that had only long ago raged with rivers, quaked with active faults, and sizzled with towering volcanoes. Its glory — geological, meteorological, and maybe even biological — resides mostly in the distant past.

MRO has, again, changed the way we think about our anti-sunward neighbor. It has revealed that, even today, Mars is constantly changing. We’ve seen the dark, spiny splats of fresh impact craters that were not there a decade ago, and the sinuous shadows of giant dust devils caught writhing across the surface, leaving dark, convoluted doodles in the bright sand.

Some of the most striking images are of the strange polar terrains where seasonal cycles of freezing, thawing, condensation, and sublimation produce shifting, animated forms resembling giant spiders or towering trees. Our new ability to monitor seasonal changes has led to the discovery of possible evidence that traces of briny liquid water can briefly flow down steep crater walls in the hottest days of Martian summer.

Someday, perhaps soon, humans will walk across the Red Planet’s dusty, variable vistas (see page 84 of Sky & Telescope's June issue). These adventurers will ride ships powered by the excitement of our current discoveries, and they’ll follow the maps made by MRO.

No comments:

Post a Comment