The Frozen Plain of Pluto

New images from NASA's New Horizons spacecraft reveal an ice-covered plain on Pluto that looks remarkably young and fresh.

If, say, six months ago, you'd asked a planetary scientist what the surfaces of Pluto and Charon would look like when seen up close by New Horizons, the likely answer would have been, "Cratered and ancient." The consensus view was that these bodies are too small to have retained much internal heat for 4½ billion years, so they most likely froze throughout early on and have been collecting impact craters on their surfaces ever since.

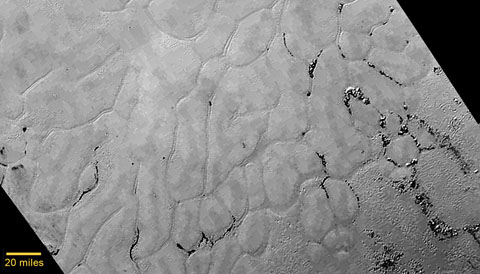

In the center left of Pluto’s vast heart-shaped feature (informally named Tombaugh Regio) and north of the icy mountains revealed previously, New Horizons has recorded a vast, craterless plain that appears to be no more than 100 million years old. Informally named Sputnik Planum (Sputnik Plain), the surface appears to be divided into irregularly shaped segments rimmed by narrow troughs.

NASA / JHU-APL / SWRI

NASA / JHU-APL / SWRI

But images and other data from New Horizon are telling a very different story. Today, for example, the mission's scientists released an image of a frozen plain that is amazing as much for what it doesn't show (impact craters) as for what it does. According to Jeff Moore (Southwest Research Institute), who heads the scientists assessing geology and geophysics, the utter lack of impacts means this surface can't be more than 100 million years old — a long time by human standards but really just 2% of the solar system's age — and it's likely much younger. "It could be a week old for all we know," he says.

The flat plain corresponds to the western half of the broad, bright, heart-shaped region that's unofficially named Tombaugh Regio. (Seemingly on a naming binge, the team has dubbed this smooth portion of it Sputnik Planum, to honor Earth's first artificial satellite, and the mountains seen in an earlier image Norgay Montes, for the pioneering Nepalese mountaineer who accompanied Edmund Hillary to the summit of Mount Everest in 1953.)

Strange winding depressions flute the surface of Sputnik Planum and carve it into quasi-polygonal sections roughly 20 to 40 miles (30 to 60 km) across. At one end of Sputnik Planum, clusters of knobby hills jut up from these shallow depressions; elsewhere dark material appears to have collected in the troughs.

This craterless plain "has some story to tell," Moore notes, but for now the mission scientists really can't do more than speculate as to what's going on. For example, the grooving could be an expression of convection driven by the cyclic freezing and sublimation of N2 and CO ice just below the surface (akin to a boiling pot of oatmeal), or they could be contraction features analogous to mudcracks on Earth. (To get a sense of the terrain, view this flyover animation of the plain.)

Additional clues have come from Alice, the spacecraft's ultraviolet spectrometer, which shows a concentration of frozen carbon monoxide (CO) in this general area. It's too soon yet to know whether it's relatively pure or just mingled with frozen nitrogen ice on the surface, but principal investigator Alan Stern says no other concentration of CO exists anywhere else on the sunlit portion of Pluto's globe.

Whiff of the Wisps

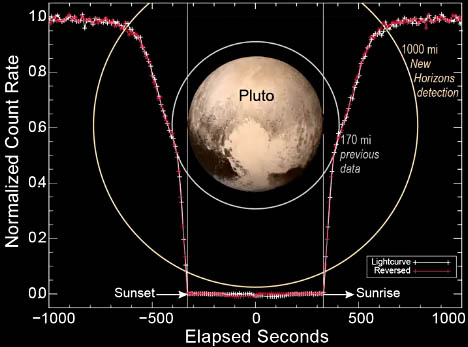

A trace of Pluto's atmosphere as recorded during an occultation of the Sun as seen from New Horizons

NASA / JHU-APL / SWRI

NASA / JHU-APL / SWRI

In the last two days, the team has gotten its first look at crucial atmospheric data obtained when Pluto passed directly between the spacecraft and the Sun. The resulting occultations -- one on each side of Pluto's disk -- provided a very sensitive probe of the density and structure of Pluto's ultrathin atmosphere. Randy Gladstone (Southwest Research Institute) reported that the nitrogen-dominated atmosphere actually extends out at least 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from Pluto's surface and that it's much the same on both sides of the globe — an indication of stability and lack of wholesale turbulence.

The large radial extent adds to the growing evidence that Pluto is losing what little gas it has at a fairly rapid rate, roughly 500 tons per hour. "We know there's methane in the atmosphere," explains Fran Bagenal (University of Colorado). "It absorbs sunlight, heats up, and gives the gas the energy it needs to escape."

Once in space, explains Fran Bagenal (University of Colorado), the nitrogen molecules are vulnerable: the Sun's ultraviolet radiation, even though 1⁄1,000 weaker than it is here at Earth, ionizes the molecules. Then they're swept up by the high-speed solar wind flowing past Pluto at hundreds of miles per second, creating an ion tail that extends outward, away from the Sun.

Bagenal says the team should have a better estimate of the atmospheric escape rate in August, once all the observations accumulated by the spacecraft's solar-wind and energetic-particle instruments are safely on the ground.

In fact, now that the encounter is largely over, New Horizons is focused on trickling its 50 gigabytes of results back to Earth. By the end of next week, when NASA plans to hold another press briefing, about 5% or 6% of that should be in mission scientists' hands.

No comments:

Post a Comment