40th Anniversary of Viking’s Red Planet Rendezvous

July 20. The date is instantly recognizable to space enthusiasts as theANNIVERSARY of the Apollo 11 Moon landing in 1969. But another major space-exploration anniversary shares the same date. Can you name which one? Perhaps if you’re a Baby Boomer.

of the Apollo 11 Moon landing in 1969. But another major space-exploration anniversary shares the same date. Can you name which one? Perhaps if you’re a Baby Boomer.

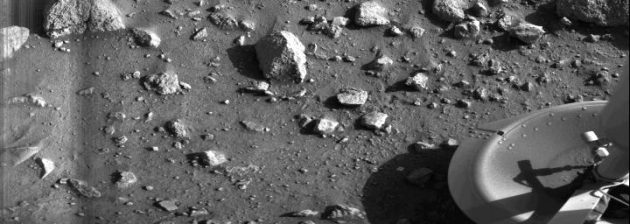

On July 20, 1976, NASA’s Viking 1 lander touched down safely on Mars, becoming the first spacecraft to do so. The milestone was originally scheduled for July 4th, to coincide with the U.S. bicentennial celebration. But images from the Viking 1 orbiter — the lander’s mother ship — revealed the planned landing site to be more boulder-strewn than expected. It took 16 days for mission scientists to find a less hazardous alternative. Two months later, on September 3rd, the twin Viking 2 lander also made a successful touchdown.

This past Saturday, July 16th, some 200 of the mission’s surviving scientists and engineers and their families, along with many younger space explorers inspired by the Vikings, gathered at the Wings Over the Rockies Air & Space Museum in Denver, Colorado, to celebrate the 40thANNIVERSARY of the Viking 1 landing.

of the Viking 1 landing.

The event was organized by Rachel Tillman, executive director of the Viking Mars Missions Education and Preservation Project. As the daughter of Jim Tillman, a member of Viking’s meteorology team, Rachel literally grew up with the mission and has known most of its team members — if not personally, at least by name — for nearly her entire life.

Why Denver? Because it’s home to aerospace giant Lockheed Martin, which in an earlier incarnation (as Martin Marietta) designed, built, tested, and flew the Viking landers. Mission control and the science operations center were located at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, which is where the action was during that historic summer of 1976 — other than on Mars itself, of course!

Celebrating Once and Future Mars Exploration

Throughout the day visitors to the museum browsed special exhibits about Viking and subsequent Mars missions. They also had the opportunity to interact one-on-one with scientists and engineers from across the country. Most of the museum’s younger visitors (and many of their parents) had never heard of Project Viking and were excited to hear stories of what it was like to be part of such an ambitious undertaking.

After the museum closed to the public, Tillman and her crew set up a lavish barbecue buffet dinner and invited several senior Vikings to offer brief reminiscences. Pat DeMartine, who developed software for the spacecrafts’ computers, recalled the team’s collective opinion that there was maybe a 50% chance that one of the two landers would make it to the surface intact. He described the fact that they both did, and then operated on Mars for several years beyond their planned 90-day lifetimes, as “spectacular, unbelievable!”

Ben Clark, who worked on the landers’ soil-chemistry experiment, talked about the aspect of Viking that attracted the most attention from the news media and public: the search for evidence of past or present life on the Red Planet. Each lander carried three instruments designed to look for different chemical or biological signatures of living (or once-living) organisms. When the landers’ soil scoops delivered samples to the three experiments, both spacecraft produced similar results: one instrument reported a positive detection, another a negative one, and the third an ambiguous one. Clark said this lack of clear evidence for life killed NASA’s appetite for Mars exploration for the next 20 years.

Thanks to a new generation of planetary scientists and NASA leaders, Mars missions resumed in the 1990s. A fleet of increasingly sophisticated orbiters, landers, and rovers — not only from the U.S. but also from Europe, Japan, and India — have built a strong case for a warmer, wetter Mars in the past and possible seasonal flows of water in the present. Since liquid water is considered a fundamental requirement for life, interest in Mars is enjoying a tremendous resurgence, much to the aging Vikings’ delight.

Return of the Viking Interns

The Group 2 Viking interns, who spent July 1976 at the Jet Propulsion Lab, pose with an engineering model of the Viking Mars landers. Author Rick Fienberg is in front, second from the right, and next to him, in red pants, is Ken Carpenter.

NASA / JPL

NASA / JPL

The youngest representatives from the Viking mission at Saturday’s gala were a dozen 60-somethings who had been among the 58 undergraduate interns chosen from more than 600 applicants to spend a month at JPL during the summer of ’76. The internship program — the first of its type at NASA — was the brainchild of lander-imaging-team leader Tim Mutch of Brown University and his colleague Carl Sagan of Cornell University, who was not yet a household name (hisCosmos TV series was still four years away). Its success prompted future missions to offer similar opportunities to college students.

Many Viking interns went on to have illustrious careers in astrophysics, planetary science, aerospace engineering, and related fields. The names of quite a few of them are likely familiar to readers of Sky & Telescope. Among them:

- Steve Albers, who in July 1991 produced what was, at the time, widely regarded as the best-ever photograph of a total solar eclipse;

- Ken Carpenter, one of NASA’s top scientists on the Hubble Space Telescope project;

- Andy Chaikin, who worked at S&T in the 1980s and wrote the best-selling book A Man on the Moon, which was made into an HBO mini-series;

- Nathan “Chip” Cohen, who studied under Carl Sagan at Cornell University, wrote the acclaimed book Gravity’s Lens, and is now a telecommunications tycoon;

- Paul Spudis, a geologist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute and the world’s leading advocate of developing the Moon’s resources;

- David Thompson, the CEO of Orbital Sciences Corp., whose Cygnus spacecraft are resupplying the International Space Station; and...

- me! I worked at S&T for 22 years beginning in 1986, serving the last 8 as Editor in Chief, and am now the press officer for the American Astronomical Society.

No comments:

Post a Comment