No Dark Matter from LUX Experiment

An underground detector reports zero detections of weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), the top candidate for mysterious dark matter.

The Davis cavern, deep within what used to be the Homestake Mine, before the placement of the LUX experiment.

LUX / Sanford Underground Research Facility

LUX / Sanford Underground Research Facility

Founded in 1876, the town of Lead in South Dakota hummed along as a mining community for more than a century. Homestake Mine employed thousands in the largest, deepest, and most productive gold mine in the Western Hemisphere.

Now scientists are using it to mine for gold of a darker kind.

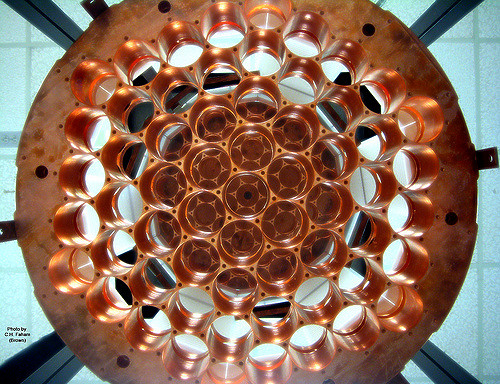

More than a mile underground, where miners once accessed precious ore, sits a 3-foot-tall, dodecagonal cylinder of liquid xenon. The 122 photomultiplier tubes at the container’s top and bottom await the glitter of light that would signal an elusive dark matter shooting through the cylinder and interacting with one of the xenon atoms. But after more than a year of data collecting, the Large Underground Xenon (LUX) experiment announced last week at the Identification of Dark Matter 2016 conference that they’re still coming up empty-handed.

A Physicist’s Gold Mine

Weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) are the top candidates for dark matter, the invisible stuff that makes up about 84% of the universe’s matter. By definition, dark matter doesn’t interact with light, nor does it interact via the strong force that holds nuclei together. And while we know it interacts with gravity, that interaction leaves only indirect evidence of its existence, such as its effect on galaxy rotation.

This bottom view shows the photomultiplier tube holders in the LUX experiment. Find more images on LUX's Flickr account.

LUX / Sanford Underground Research Facility

LUX / Sanford Underground Research Facility

But WIMP theory says dark matter particles should also interact via the weak force, a fundamental force that governs nature on a subatomic level — including the fusion within the Sun. So a WIMP particle should very rarely smash into a heavy nucleus, generating a flash of light. The chance for a direct hit is very, very low, but 350 kilograms (770 pounds) of liquid xenon in the LUX experiment should have good odds.

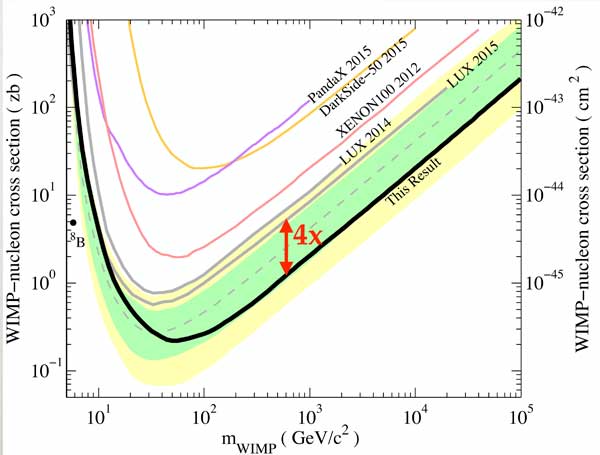

After just three months of operation, in 2013 the LUX experiment had already reported a null result. At the time, the experiment had probed with a sensitivity 20 times that of previous experiments (check out the graph here to see how three months of LUX ruled out numerous WIMP scenarios).

A new 332-day run began in September 2014, and the preliminary analysis announced last week probes four times deeper than the results before. Yet despite a longer run time, increased sensitivity, and better statistical analysis, the LUX team still hasn’t found any WIMPs.

Simply put: either WIMPs don’t exist at all, or the WIMPs that do exist really, really don’t like interacting with normal matter.

It’s also worth noting that LUX isn’t just looking for WIMPs. The WIMP scenario is the primary one it’s testing, and the one that last week’s announcement focused on. But more results are forthcoming about LUX results on dark matter alternatives, such as axions and axion-like particles.

Not All That’s Gold Glitters

The non-finding may not win any Nobel Prizes, but in a way it’s great news for physicists. Numerous experiments (such as CDMS II, CoGeNT, and CRESST) had found glimmers of WIMP detections, but none had found results statistically significant enough to be claimed as a real detection. The LUX results have been helpful in ruling out those hints of low-mass WIMPs.

For the technically minded, this is the result that was presented at the Identification of Dark Matter conference in Sheffield, UK. The plot shows the possibilities for dark matter in terms of its cross-section — the bigger the value, the more easily it interacts with normal matter — and its mass. (The mass is given in gigaelectron volts per speed of light squared, which translates to teeny tiny units of 1.9 x 10-27 kg.) LUX's most recent results rule out any dark matter particles with mass and cross-section that place them above the solid black line. The upshot is that LUX, the most sensitive dark matter experiment to date, is narrowing the playing field, especially for low-mass WIMP scenarios.

“It turns out there is no experiment we can think of so far that can eliminate the WIMP hypothesis entirely,” says Dan McKinsey (University of California, Berkeley). “But if we don't detect WIMPs with the experiments planned in the next 15 years or so . . . physicists will likely conclude that dark matter isn't made of WIMPs.”

That’s why — despite not finding any WIMPs this time around — the LUX team continues to work on the next-gen experiment: LUX-ZEPLIN. Its 7 tons of liquid xenon should begin awaiting flashes from dark matter interactions by 2020.

Three years of data from LUX-ZEPLIN will probe WIMP scenarios down to fundamental limits from the cosmic ray background. In other words, if LUX-ZEPLIN doesn’t detect WIMPs, they don’t exist — or they’re beyond our detection capabilities altogether.

No comments:

Post a Comment