Exoplanet Found Around Proxima Centauri

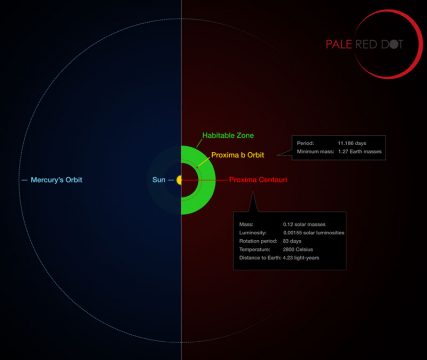

This infographic compares the orbit of the newfound exoplanet around Proxima Centauri (labeled "Proxima b") with the innermost solar system. Proxima Centauri is smaller and cooler than the Sun, and the planet orbits much closer to its star than Mercury does to the Sun. As a result it lies well within the "habitable zone," where liquid water could exist on a planet's surface if the world has the right composition and atmosphere.

ESO / M. Kornmesser / G. Coleman

ESO / M. Kornmesser / G. Coleman

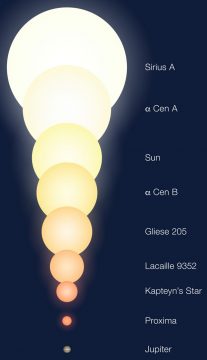

The closest star to our solar system is currently Proxima Centauri. Proxima is a small, red M dwarf only about half as hot as the Sun and 14% as wide. It’s member C of the Alpha Centauri system, a triple-star system that lies just over 4 light-years away.

And now, astronomers say, they’re sure Proxima Centauri has a planet.

The world, Guillem Anglada-Escudé (Queen Mary University of London) and colleagues report August 24th in Nature, has a mass at least 1.3 times that of Earth, meaning it’s potentially rocky. It orbits the star every 11.2 days at a distance of only 0.05 times the Earth-Sun distance, or roughly one-tenth the space between Mercury and the Sun. That places it right in the star’s putative habitable zone.

We’ve had our hopes raised for alien worlds in the Alpha Centauri system before. For example, in 2012 observers reported that they’d found what looked like an Earth-mass planet hugging the orange Sun-like star Alpha Centauri B. But follow-up work by other researchers raised a red flag. The putative planet has sinceproved to be a subtle “ghost” in the data, created by how the original team sliced up the observations for analysis.

But the new exoplanet, dubbed Proxima Centauri b, appears to stand on more solid ground. Astronomers had suspected for some time that Proxima had a planet: data from two European Southern Observatory (ESO) spectrographs had found a shift in the star’s light that seemed to repeat every 11.2 days. This shift might have come from a tiny wobble in the star’s position toward and away from us, due to the gravitational tug of an orbiting planet.

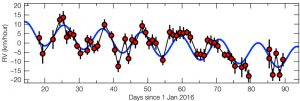

This plot shows how the motion of Proxima Centauri towards and away from Earth (y-axis) changed with time over the first months of 2016. Sometimes Proxima Centauri is approaching Earth at about 5 km/h (1.4 m/s or 4.6 ft/s) — normal human walking pace — and at times receding at the same speed. This regular pattern of changing radial velocities repeats with a period of 11.2 days and results in tiny Doppler shifts in the star's light, making the light appear slightly redder, then bluer. Careful analysis showed that these Doppler shifts are created by a planet with a mass at least 1.3 times that of the Earth, orbiting about 7 million kilometers from Proxima Centauri — only 5% of the Earth-Sun distance.

ESO / G. Anglada-Escudé

ESO / G. Anglada-Escudé

But being an M dwarf, Proxima is a fairly active star. Astronomers didn’t have enough data to tell if the signal was instead just muck in the starlight from flares and other stellar hubbub.

So Anglada-Escudé’s team started the Pale Red Dot campaign to find out if the planet was real. The campaign had a two-pronged approach. First, the team convinced ESO to let them use the renowned HARPS spectrograph on La Silla’s 3.6-meter telescope in Chile to observe Proxima Centauri for 20 minutes every clear night from January 19th to March 31st this year. Second, a network of other telescopes simultaneously watched for changes in the star’s brightness, pinpointing the star’s rotation period and recording if any flares went off. This work is called photometry.

The team found that the new, 2016 HARPS data also contained a periodic signal, just like the one in the archival data. And when the researchers combined both sets of data into one and analyzed the whole, 16-year-spanning shebang, the statistical significance (read: “how believable the signal is”) went “sky high,” Anglada-Escudé said in a press conference. There’s no doubt that it’s real.

But the real kicker is the photometry. Proxima itself didn’t do anything during the observations that could explain the periodic signal. Instead, the best solution is a planet.

M Dwarfs: They’re Everywhere

This graphic shows the relative sizes of several stars and Jupiter, including the three known members of the Alpha Centauri system. The Sun is between Alpha Centauri A and B. The Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI) at the ESO Paranal Observatory measured the stars' angular sizes (besides the Sun's).

ESO

ESO

The existence of Proxima Centauri b is far more likely than the now-disproven Alpha Cen Bb, for three reasons, says exoplanet researcher Debra Fischer (Yale). One, the signal is stronger: the world causes a wobble of about 1.4 m/s, safely above the observations’ 1 m/s error range. Two, the Pale Red Dot campaign’s merciless every-night attack proves the signal repeats the way it had seemed to.

And three, the math is better: astronomers overall are improving their statistical toolkit, and this new analysis holds more water. In fact, if you take a gander at the paper, you’ll see that in many ways it’s a stats paper — discussions of “Bayesian framework,” “likelihood function,” and so forth are prominent.

“I’m very excited about this planet, but not terribly surprised,” says David Charbonneau (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics), who heads up the MEarth Project to look for exoplanets around M dwarfs. A few years ago, he and Courtney Dressing (now at Caltech) used Kepler data to estimate that one out of every four M dwarf stars has a planet that’s at most 1.5 times as wide as Earth. Expand the size to twice that of Earth, and the rate goes up to nearly one out of every two. “With those odds, it isn’t at all that surprising that the closest M dwarf has one,” he explains.

But we don’t know how big Proxima Cen b is. Astronomers’ favorite way of measuring a planet’s radius is watching it cross in front of its star from our perspective: how much light the exoplanet blocks depends on its size. But MEarth and other projects have failed to detect a transit. That’s to be expected, Charbonneau says: geometrically speaking, there’s only a 1.5% chance that the world passes across the face of Proxima.

That means the newly discovered planet is probably no target for NASA’s upcoming Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), says mission team member Sara Seager (MIT). However, in the grand scheme of things the discovery is good news for TESS, she adds, because it “buoys our confidence that TESS will find a bonanza of planets transiting nearby M dwarf stars.”

This wide-field image shows a stretch of the Milky Way visible from the Southern Hemisphere. The Carina Nebula (NGC 3372) glows in red at the right of the image, and at center is the constellation Crux (The Southern Cross). The bright yellow-white star at far left is Alpha Centauri. Alpha Centauri is a system of three stars: A and B orbit each other about every 80 years, while C, also known as Proxima Centauri, lies much farther out (as clear from this zoomed-in image) and takes a few hundred thousand years to go around the pair.

A. Fujii

A. Fujii

Although it sure looks like Proxima Cen b is real, astronomers always want more data. The best way to follow up may be taking actual pictures. The star is so close that upcoming adaptive optics instruments will be able to directly image the planet — assuming they can properly block out the star’s light to see the world, which is only 35 milliarcseconds (about1⁄100,000°) away from it. They may also be able to tease out reflected light from any atmosphere, revealing its composition.

In addition, there’s the upcoming ESPRESSO spectrograph on VLT, which will go online in 2017. With it, says Fischer, “demonstrating the existence of Proxima Cen b should be like shooting fish in a barrel.”

A Habitable Planet Around Proxima Centauri?

Whether Proxima Cen b actually is habitable remains a wide-open question. Technically it lies at the right distance from its star that, if it has the right composition and atmosphere, it would be the right temperature to sustain liquid water on its surface.

This artist’s impression shows what the sky might look like on Proxima Centauri b if the planet has a surface. The exoplanet orbits the red dwarf star Proxima Centauri, currently the closest star to the solar system at 4.2 light-years. The other two members of the Alpha Centauri triple, Alpha Centauri A and B, would appear in the sky, too.

ESO / M. Kornmesser

ESO / M. Kornmesser

But, the authors stress, astronomers only know three things about this world: its mass, orbital period, and distance from the star. It’s not even clear whether Proxima Cen b is rocky — the 1.3 Earth masses is a lower limit; the team can’t give an explicit, upper cutoff for how hefty it might be. Still, coauthor Ansgar Reiners (Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany) says previous work has shown that massive planets generally don’t form around stars this small. His gut instinct is that the world probably doesn’t weigh more than a few Earths. That could still make it a mini-Neptune.

If the planet does have a surface, whether it has water will depend on how it formed and what happened to it soon after — did it coalesce far away from the star, where ices reign, and then migrate in, carrying that water with it? Did it form from dry rocks and so never picked up any water? We don’t know. Artie Hatzes (Thuringian State Observatory, Germany), who raised the alarm about Alpha Cen Bb a few years ago, goes so far as to suggest in his Nature perspective article that we should instead say Proxima Cen b lies in the “temperate zone,” not the “habitable zone,” the latter of which is misleading.

It’s also unclear just how much the M dwarf’s active personality would harm the planet. Proxima Centauri b receives roughly 100 times more X-ray radiation from its star as Earth does from the Sun (that’s a revised estimate from the more conservative 400x in the paper). What that means for habitability is anyone’s guess. A lot will depend on what the star did in its early days, which astronomers don’t know: M dwarfs are much more mysterious in this regard that stars like the Sun, Reiners says. If Proxima Centauri formed with Alpha Centauri A and B — and astronomers aren’t 100% sure Proxima is in fact bound to the tighter pair — then it’s likely the same age as they are, or roughly 5 billion years, on par with the Sun.

Lastly, the planet is probably tidally locked in synchronous rotation, which means it always points the same face at Proxima, just as the Moon always points the same face at Earth. That’s not a death knell for habitability, but it does change the requirements for atmospheric circulation.

No comments:

Post a Comment