How Dead Galaxies Stay Dead

A galaxy in the midst of a merger isn’t forming stars, even though it could. Astronomers think the galaxy’s central black hole might be the reason why.

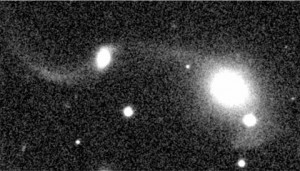

This image from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey shows the interacting galaxies Tetsuo (left) and Akira. Astronomers see signs of a gaseous outflow from Akira, which is a bulgy, red-and-dead galaxy. The image was taken through an r-band filter, which means it lets through light in and near the red part of the visible spectrum, in this case centered near 620 nm.

SDSS

SDSS

Galaxies form stars from cold gas. The more gas a galaxy has, the more stars it could in principle create. But long ago astronomers discovered that something is stopping starbirth in many galaxies. Up to three-quarters of the old, “red-and-dead” galaxies still have enough gas to fuel star formation, yet only maybe 15% of them have stellar nurseries. What gives?

The short answer is, the gas is too warm. Warm gas won’t collapse into stars. But that raises the question, why is the gas warm? One popular idea is that the galaxy’s central black hole is to blame. If the black hole is scarfing down gas, it can shoot out jets, or winds can blow off the disk of material feeding it. The jets and winds would stir up gas in the galaxy and keep it from cooling.

Astronomers do see signs of this process in galaxies with the most enthusiastically gobbling black holes. But they’ve had trouble confirming this process is at work in more typical, quieter galaxies.

Edmond Cheung (University of Tokyo) and colleagues might now have done just that. The team studied about 700 galaxies observed with one of the latest iterations of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, called Mapping Nearby Galaxies at Apache Point Observatory (MANGA). About 5% were of the red and dead variety, yet they seemed to have gas flowing out of them. That implies something is going on inside, whether it be stars dramatically sloughing off layers or a black hole bullying gas.

The team homed in on a single galaxy, which they nicknamed Akira. Akira is in the midst of merging with a much smaller galaxy (moniker Tetsuo) that’s about one-tenth as massive. (For the curious, these names come from characters in a manga comic.) Mergers often trigger bursts of starbirth. Yet, although observations show that Akira has gas, it’s not churning out stars.

The team argues in the May 26th Nature that that might be because of the black hole. The black hole is active — although not egregiously so: it doesn’t have big jets — and the researchers estimate that it could be putting out enough energy in small-scale jets or winds to literally stir up trouble for star formation and create the outflow they detect.

The connection is only “qualitative,” cautions Marc Sarzi (University of Hertfordshire, UK) in his opinion piece in Nature — there’s no smoking gun here. But Akira is one more puzzle piece in the picture we’re building of how supermassive black holes affect the galaxies they live in.

No comments:

Post a Comment