Curiosity Sees Seasonal Trends on Mars

During two Martian years, Curiosity tracks seasonal patterns in local atmosphere, temperature, and maybe even methane.

Curiosity measured seasonal patterns that show the local atmosphere is clear in winter, dustier in spring and summer, and windy in autumn. The visibility in Gale Crater is as low as 20 miles (30km) in summer and as high as 80 miles (130km) in winter.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

Last week, Curiosity completed its second Martian year, even though it landed in Gale Crater almost four years ago. Mars is much further from the Sun than Earth is, so the Red Planet takes nearly twice as long to complete one orbit around our star: 687 days to our planet’s 365 days.

For the past two Martian years, Curiosity has been busy collecting rock samples. Those have revealed that this part of Mars was once habitable. But the rover has also been measuring atmospheric pressure, temperature, and methane levels. These measurements show seasonal changes, much like Earth’s yearly rhythm.

Seasons, both on Mars and on Earth, happen because of the planet’s tilt—its rotation axis inclines 25 and 23 degrees from vertical, respectively. Mars also has a longer elliptical orbit compared to Earth, causing longer winters and shorter summers in its southern hemisphere.

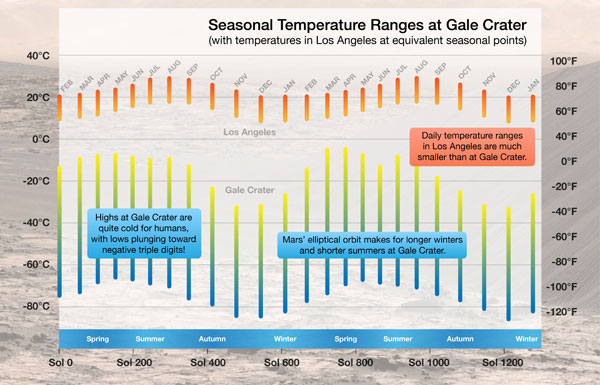

Curiosity found that seasonal temperatures at Gale Crater follow a periodic pattern like we see in Los Angeles—though at much lower temperatures, as seen in this graphic chart. Temperatures in LA range from 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius) in the summer to 50 F (10 C) in the winter. Curiosity’s Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS) has measured variations in temperatures ranging from 60.5 F (15.9 C) on a summer afternoon to -148 F (-100 C) on a winter night.

The temperature on Mars and Los Angeles follows the same seasonal pattern: higher temperatures during the summer, lower temperatures in the winter.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/CAB(CSIC-INTA)

NASA/JPL-Caltech/CAB(CSIC-INTA)

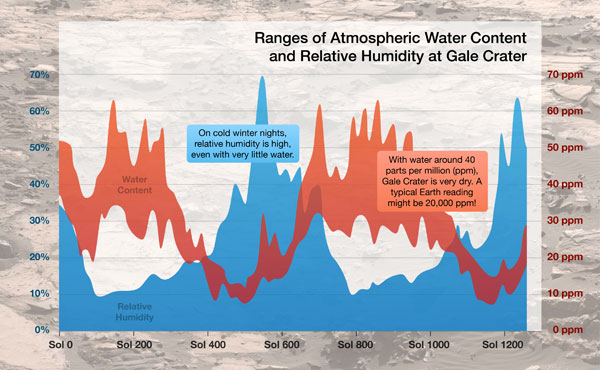

The chart also shows seasonal patterns between water content and relative humidity. The air in Gale Crater is very dry, with water content around 40 parts per million (ppm). As a comparison, a typical reading on Earth might be 20,000 ppm. Curiosity found that during the southern hemisphere’s summer, relative humidity—a measure of how close water vapor is to saturating the air—is low. In the winter, even though there is little water content in the air, the temperature drops so much that humidity actually goes up to 70%.

On Earth, we associate humidity with warm environments, like Florida in the summer, but high relative humidity can also happen in the winter. “For a given amount of water vapor, the colder the air gets, the closer it is to saturating, and the relative humidity goes up,” says project scientist Ashwin Vasavada (JPL). Gale’s winter humidity is high enough that frost might form on the ground, but the rover hasn’t found any.

Curiosity also measured seasonal patterns between water content and relative humidity. The humidity is highest in the winter, even if there is low water content in the atmosphere.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/CAB(CSIC-INTA)

NASA/JPL-Caltech/CAB(CSIC-INTA)

Changing Methane Levels

Another interesting trend from the two-year cycle is the periodic methane levels. During Curiosity’s two Martian years at Gale Crater, it has also been measuring background methane levels using the tunable laser spectrometer in its Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) suite of instruments. In the rover’s first cycle, it detected a spike in methane to 7 parts per billion by volume (ppbv) in the local atmosphere. This sparked media attention, especially because methane’s existence on Mars was previously a controversial issue.

Methane is the most abundant hydrocarbon in the solar system, but it must be replenished—either by biotic or abiotic activity — because it is easily destroyed by sunlight’s ultraviolet rays. So when Michael J. Mumma (NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center) and Vladimir A. Krasnopolsky (Catholic University of America) found methane on Mars in 2004, scientists met it with skepticism.

Once Curiosity landed, it began using the SAM instruments to analyze the Martian atmosphere and reported an upper limit of just 0.18 ppbv with an uncertainty of ± 0.67ppbv. Because the levels were so low, mission scientists concluded there was no trace of methane. But when the rover detected the 7ppbv spike during its first autumn, it confirmed methane’s presence in the atmosphere, though scientists are still not sure where it came from.

The methane measurements Curiosity has taken over the last two Martian years also show a “background” level that falls mostly between 0.3 and 0.8 ppbv and possibly follows seasonal patterns. The 7 ppbv spike happened for several weeks during the first autumn, so mission scientists checked carefully for a repeat spike during the second autumn. But concentrations stayed low.

“Doing a second year told us right away that the spike was not a seasonal effect,” said Christopher Webster (JPL) of the SAM team in a press release. "It’s apparently an episodic event that we may or may not ever see again.”

The mission continues to monitor methane levels, which appear to be even lower in autumn than in other seasons. If confirmed, the low autumn level could be a delayed reaction to summer’s high ultraviolet radiation.

Technological innovations, and Curiosity’s continuous measurements, have allowed scientists to resolve the methane controversy in less than a decade. Only time will tell what other seasonal patterns Curiosity finds.

https://linksredirect.com/?pub_id=11719CL10653&url=http%3A//www.makemytrip.com/flights/

No comments:

Post a Comment