Astronomy - Winter Nights Exploring the Lunar Arctic

Put on a coat, set up your scope, and become a polar explorer as we visit off-the-beaten-path craters and maria in the Moon's arctic vastness.

January is often the coldest month of the year, a fact residents of the Upper Midwest have been acutely aware of the past several weeks. Some nights it's actually been colder than the North Pole, where temperatures have been bobbing around –20°F (–29°C) the past few days. Let's take that as an omen, a sign to explore things north of normal. What better place to start than the Moon?

The Moon rotates at a constant rate, but because it orbits the Earth in an ellipse, its distance and speed vary, causing the Moon's rotation to sometimes lead and other times lag behind its orbital position. This disconnect between constant rotation speed and inconstant orbital speed exposes slivers of the lunar farside just beyond the east and west limbs — up to ±8° of additional lunar longitude.

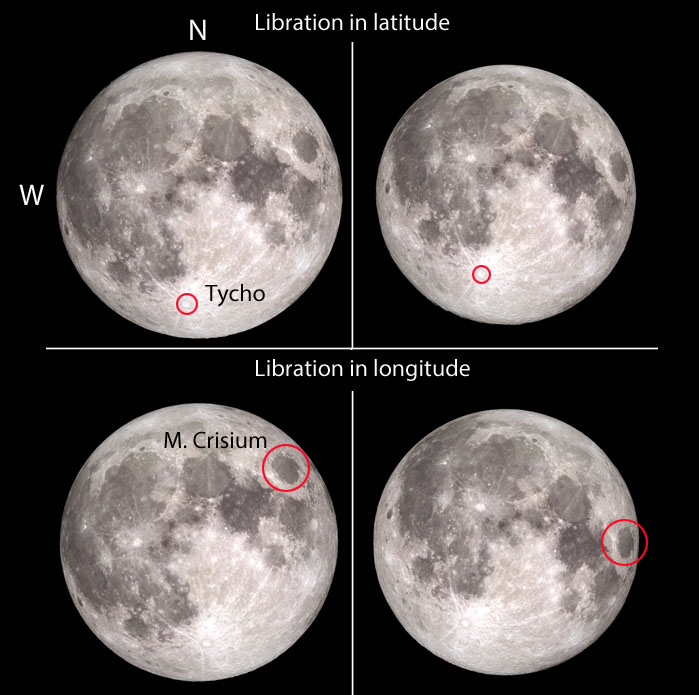

The Moon appears to "nod" toward and away from Earth (top panel) due to its tilted orbit and inclined axis, a phenomenon called libration in latitude. It also wobbles from side to side, called libration in longitude. Because of libration, we can see a total of 59% of the moon's surface over time. The full Moons shown are for January 12 and July 8, 2017 (top) and February 10 and August. 7, 2017 (bottom); they show their correct relative sizes.

Illustration: Bob King; Images: NASA

Illustration: Bob King; Images: NASA

Due to an effect called libration of longitude, the Moon appears to slowly shake its head "no" during the course of a month. At the same time, it also nods its head "yes," exposing up to an additional ±6.6° of latitude. That's because its orbit is inclined 5.1° to the ecliptic and its axis tilts 1.5° from vertical: 5.1+1.5 = 6.6. Thanks to libration of latitude, we can peek over the pole, so to speak, to see a bit of the farside; two weeks later we glimpse deeper into the south polar regions.

Simulated views of the Moon over one month, demonstrating librations in latitude and longitude. Also visible are the different phases, and the variations in visual size caused by the variable distance from Earth.

Tom Ruen

Tom Ruen

Over a month's time, these two factors, libration in longitude and latitude, make the Moon appear to wobble (right). It so happens that maximum "northern exposure" this month occurs on January 10th with maximum "eastern exposure" just three days later on the 13th. (That's lunar east by the way, opposite of celestial east.) Both dates coincide nicely with the time of the full Wolf Moon at 6:34 a.m. Eastern (11:34 UT) Thursday, January 12th.

But why bother exploring the lunar arctic at full Moon, a time of flat, shadowless lighting? Because it's not shadowless! This month, craters and other features along the northern limb will cast shadows before, during, and after full phase, thanks to the Moon's inclined orbit and a north-wheeling terminator.

I've always been fascinated with how the lunar terminator changes direction as the waxing Moon transitions to a waning one at full phase. When the Moon lies on or near the ecliptic, the transition is symmetrical. Shading disappears at lunar west, reappears briefly at north and south poles, and then shifts east to crinkle the eastern limb of the Moon.

When the Moon lies well south of the ecliptic as it will early this week (~4-5°), the terminator instead "rolls along" the northern limb of the moon from lunar west to east. Meanwhile, the south limb remains pasty and shadowless. When far from the ecliptic, the Moon will always display a slight phase (a northern terminator) at full. Likewise, when our satellite trucks well north of the ecliptic at full Moon, the terminator darkens its southern limb.

Telescopic observers in North or South America, especially in the western half of the viewing region, can watch the terminator subtly shadow the Moon's western limb early Wednesday evening (January 11th) and then shade the northern limb at dawn on the 12th. I always get a thrill seeing the terminator sneak around the limb, as if it's taking a "shortcut" to arrive back at lunar east.

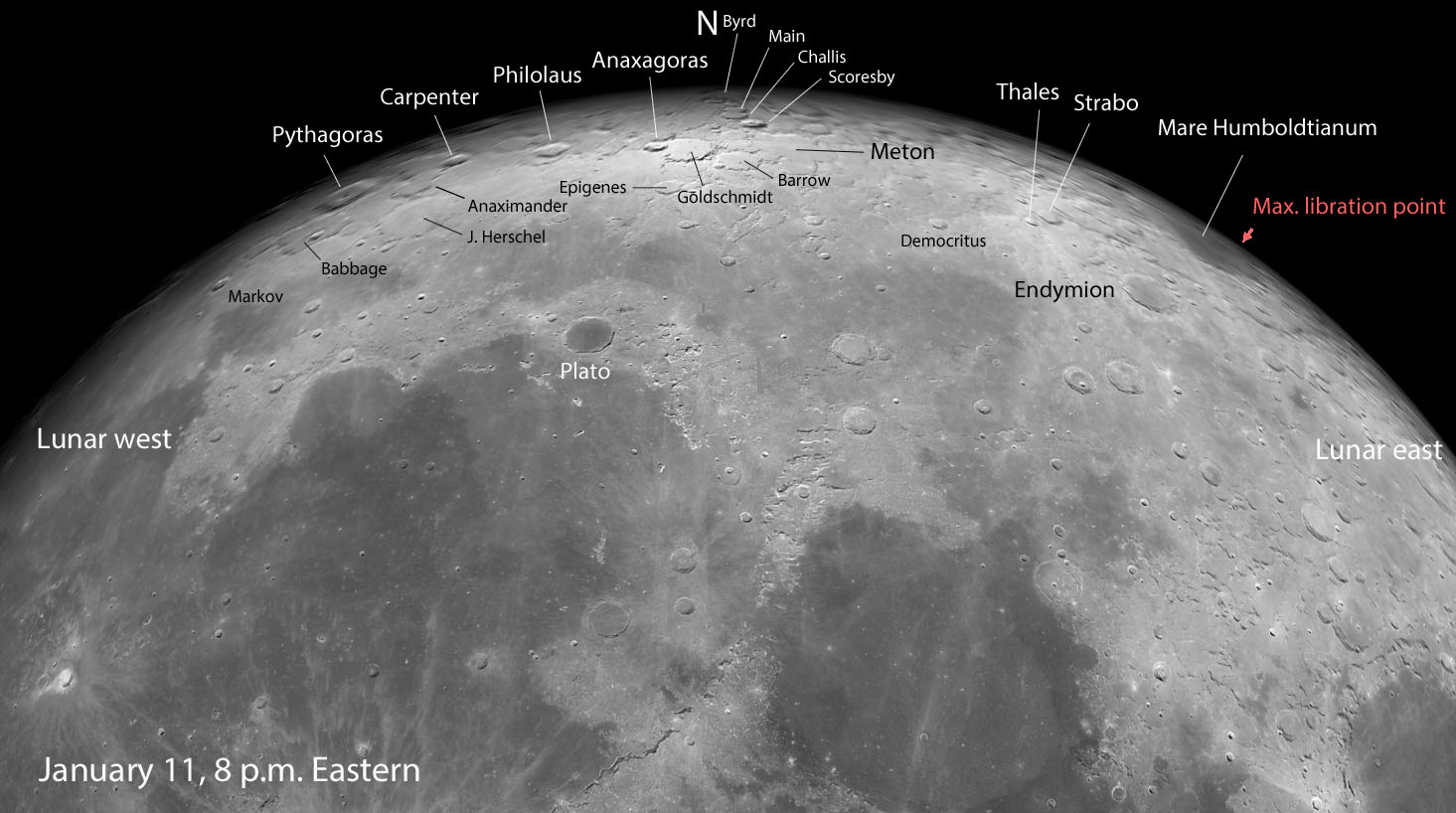

Using the easy, dark-floored crater Plato as your jumping off point, head north to the wonders of Pythagoras (80 miles in diameter) and its dual central peaks that rise nearly a mile above its floor, then crater-hop south to Babbage (89 miles) with its weird, worn polygonal walls enclosing the younger, sharp-rimmed secondary crater, Babbage A. Or hop north and east to the heavily-eroded Goldschmidt (75 miles). From there, boldly go boreal by following the chain of craters from Scoresby north to Byrd (latitude 83.5° N), a crater that's barely visible along the lunar limb. Don't forget the largish, dark patch further east, the Sea of Humboldt, named for 19th-century German naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt. Click for a larger map you can print out or download the Virtual Moon Atlas and make your own.

© Virtual Moon Atlas / C. Legrand & P. Chevalley

© Virtual Moon Atlas / C. Legrand & P. Chevalley

So what's to see? Craters and a marginal lunar sea few of us pay much attention to, what with the triumvirate of Copernicus, Kepler and Aristarchus nearby. Take the time this week to become more familiar with the northern highlights at the top of the globe. Not only is sunlight striking those northern craters at a very low angle, which helps to create shadows, the favorable northern libration tips them our way, so they're not quite as scrunched and foreshortened as usual. Both maps show the maximum libration point, a combination of the east-west and north-south extremes for a particular date.

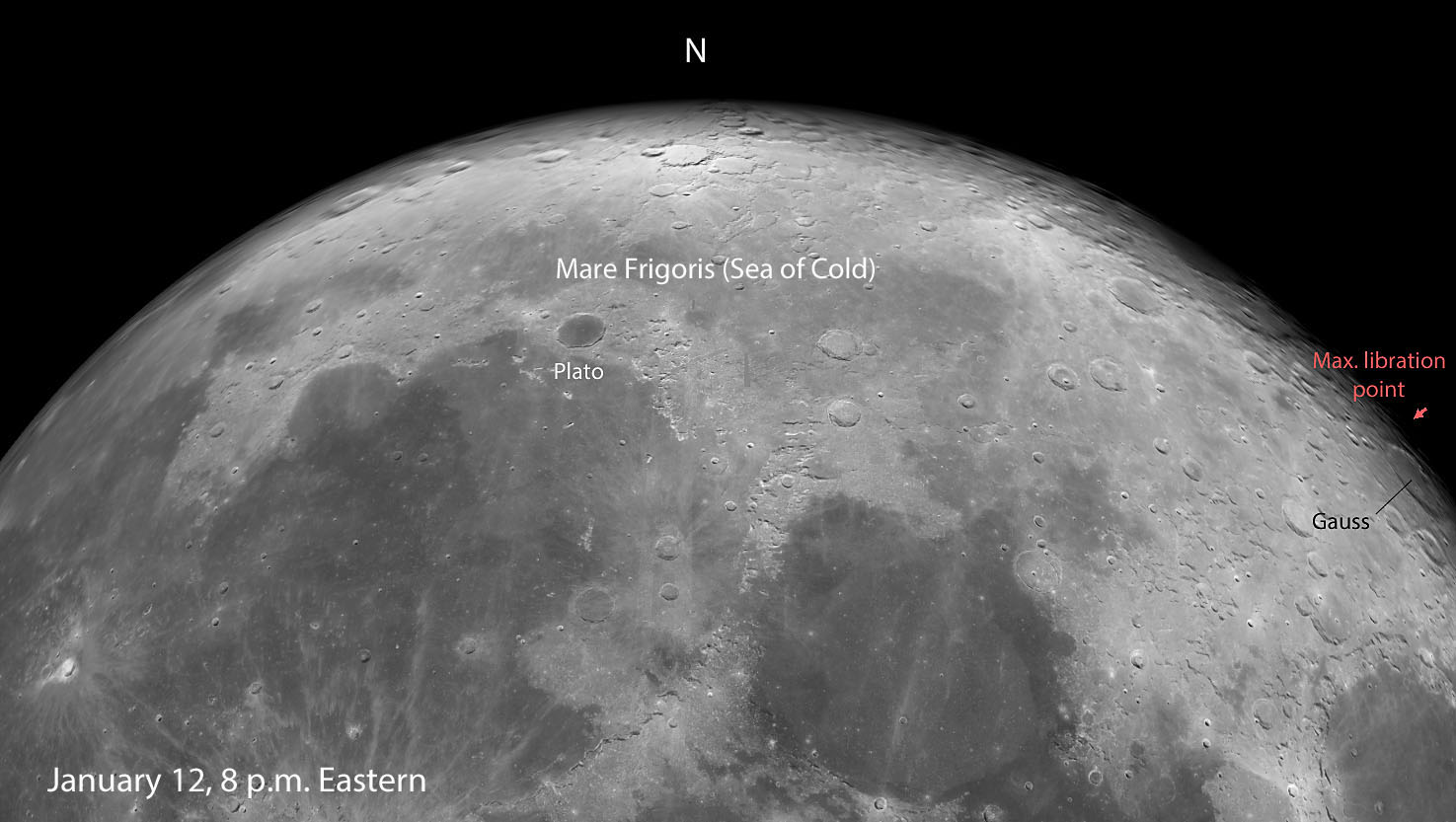

The view is similar although subtly difference on January 12th (8 p.m. Eastern time shown). Notice that the maximum libration point has slid around further east toward the prominent crater, Gauss. Gauss, like all craters along the lunar limb, appears greatly foreshortened because we see it nearly edge-on, but on Thursday evening, it will be in good view.

© Virtual Moon Atlas / C. Legrand & P. Chevalley

© Virtual Moon Atlas / C. Legrand & P. Chevalley

Highlights include the "stepping stone" craters Pythagoras–Carptenter–Philolaus–Anaxagoras–Goldschmidt. They'll take you to a large lobed crater named Meton. Its four-leaf clover shape looks to my eye like four or five once-separate craters that later flooded with lava to become one. Before leaving the area, pause at Anaxagoras (32 miles in diameter), a relatively fresh crater with a striking if foreshortened nimbus of bright rays that are prominent at full Moon.

Further east, you'll bump into the Thales–Strabo duo and then unmistakable Endymion (77 miles in diameter) with its dark, smooth floor that resembles the more familiar Plato, further west. Plato is so dark, round, and easy to pick out, it admirably serves as base camp for our polar explorations. From there, we only need cross the Sea of Cold (Mare Frigoris) and we're well on our way.

Meton, a large crater in the north polar region. has peculiar lobed outline. Seen from above, all the sausage-shaped craters appear round. This photo was taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Click for a full polar view.

NASA / LRO

NASA / LRO

You can continue your arctic adventures beyond full phase, though the amount of polar terrain shrinks as the Moon wanes. I encourage you to see for yourself how hide-and-seek libration affects crater visibility along the lunar limb. You'll see some features disappear altogether as they slink back to the farside in shadow, while others return to view. The more I look at the Moon, the more I've come to realize how it satisfies every observing challenge.

No comments:

Post a Comment